Military Tunneling

Since the invention of gunpowder, military engineers have been digging tunnels under besieged castles and then exploding large charges to bring down the walls and create gaps that could be stormed by the infantry. In fact, the term ‘sapper’ means one who digs trenches, and a ‘sap’ is a narrow trench used to undermine a fortification. In WWI both sides founded specialist Engineer Tunneling Companies as a means of attacking enemy trenches without the carnage of ‘going over the top’ into the teeth of enemy machine gun fire. One highly recommended but harrowing film on this means of warfare is ‘Beneath Hill 60’ based on the diaries of Captain Oliver Woodward.

The Development of the Tunnel Systems in Vietnam

When the Vietnamese began developing an underground tunnel network is uncertain, but the first tunnels appear to have begun during the Japanese occupation of Vietnam in WWII from 1942-1945. When the French War began in 1946, the use of tunnels by the Viet Minh expanded greatly. The French were well aware of their existence and formed their own specialist units to search and destroy those found. Many of the original tunnels were built by the Viet Minh simply as escape routes, or as hiding places when the French came to a village. Other tunnels were built by villagers for rice storage as both sides tended to forage for food when in the field, leaving the villagers to starve.

However, in the early 1960s, the arrival to Vietnam of the US Army with its ability to quickly deploy enormous firepower, changed the face of war for the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and Viet Cong (VC). If a large formation could be detected on the surface, in the jungle, or in the open, then it could be destroyed by the employment of massive aerial bombing or an artillery strike. Invisibility became essential, so tunnelling became a necessity. What may have begun as a useful protective defensive measure soon grew into an integral part of their aggressive war machine, with these underground bases becoming the holding and staging points for large-scale attacking operations.

The sophistication of this subterranean military ‘camp’ grew to include soldiers’ barracks, cooking amenities, living and training rooms, hospitals, workshops, and storage facilities. These would be connected by a series of tunnels that included escape hatches and even hidden fighting pits for sentries and snipers. At regular distances in longer tunnels there would be passing places for travellers going in opposite directions. One of the constant difficulties was ensuring there was always sufficient breathable air, so at various points concealed ventilation shafts would be driven through 10-12m of earth to the surface.

To further add to their ability to discourage intruders from entering their tunnels and underground facilities they could be booby-trapped when not occupied. A sort of macabre ‘home burglar alarm’ that could be switched off when the occupant’s returned. Some dead-end side-tunnels would be permanently booby-trapped to kill the unwary sapper who carelessly entered them. As a further defensive measure to prevent gas or smoke pumped in from penetrating the whole system and asphyxiating the occupants a sump could be installed (similar to the S-bend in a toilet) that would prevent the gas from passing that point. As a final deterrence, a defender could quietly wait in ambush as he would know the twists and turns of the labyrinth perfectly, whereas the approaching Australian sapper would have no idea what lay ahead or was waiting for him around the next corner as his would be a journey of exploration in the darkness of unmapped hostile territory.

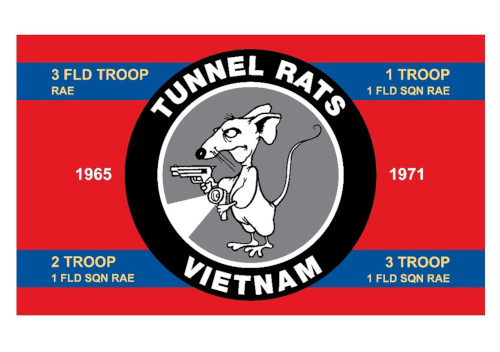

Welcome to the world of that special breed of warrior now known as ‘The Tunnel Rats’

The Australian Tunnel Rats were the men who served in the Engineer Field Troops in Vietnam (3 Field Troop and 1, 2 and 3 Troop of 1 Field Squadron, Royal Australian Engineers). Apart from those few ‘lucky enough’ to come across extensive enemy tunnel complexes to explore and clear, every member of the Field Troops took their turn underground to search, clear and destroy enemy bunker systems (often with bunkers inter-connected by small tunnels). It was not unusual for the sappers to blow up over 100 enemy bunkers in a single operation.

Enter 3 Field Troop, 1st Field Squadron, Royal Australian Engineers

3 Field Troop was the first engineer unit sent to Vietnam in support of the 1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment. In January 1965, they were deployed on Operation Crimp in the Ho Bo Woods, part of the notorious ‘Iron Triangle’. Their role was expected to be their normal one of road clearing, de-mining, and destroying any enemy facilities or caches located by the infantry. The first surprise was when they were called in to provide advice on what to do concerning some tunnel entrances that had been found.

From one entrance, an enemy soldier had killed two Australian soldiers and wounded two others. Although untrained for the task, and despite the obvious danger, volunteers entered the 60cm wide and 75cm high, lightless, claustrophobic, and almost airless tunnel armed with just a flashlight, a bayonet, and a lot of courage. The complex had been evacuated very recently but what they recovered was an intelligence bonanza. Thus began their unintentional career as Tunnel Rats. What is most surprising, given the wealth of previous tunnel clearance experience from the French era, searches carried out by the South Vietnamese Army sappers and the current US Army tunnel explorations, no ‘lessons learnt’ or operational techniques had been passed on to the Australian Field Engineers. The 3 Field Troop sappers were therefore totally untrained and unprepared for this unexpected role. The consequence of this was soon felt.

Tragedy struck on the fourth day when one of the non-commissioned officers, the 184cm tall Corporal Bob Bowtell, decided to take his turn as a Tunnel Rat. His size was his downfall. As he crawled forward into the tunnel his body prevented any air from circulating and he quickly suffocated and died. Several of his rescuers almost suffered the same fate, but fortunately they were either rescued by others or managed to climb out just in time. The deadly realities of war had been brought home to the Troop, yet none refused to continue to enter the tunnels when required.

Over the six days 3 Field Troop spent on Operation Crimp exploring the tunnels, they suffered six casualties by asphyxiation with one death and five injuries. The cause of this high level of incidents was simply referred to as 'bad air' in the tunnel, but this explanation does not pass logical scrutiny. The Vietnamese were constantly living and tunnelling in this underground labyrinth for lengthy periods without the air becoming toxic, even though there were a lot of humans down there consuming the oxygen. The cause of the asphyxiation is more likely have been the remnants of the tear gas and smoke the 3 Field Troop team members pumped into the tunnel using their newly issued 'Mighty Mite' blower system. Once it had completed its work, it was essential that fresh air should be blown in, in a sufficient quantity to re-oxygenate the tunnel and clear all remnants of the tear gas and smoke from it before the sappers entered the tunnels. Courage is no substitute for a lack of experience, effective processes, and prior training in operational techniques.

After just six days, the troop was withdrawn and moved to Vung Tau and then to Nui Dat where the 1st Australian Task Force was beginning the task of setting up their operational base. It is possible that much more could have been achieved as the tunnel stem was extensive and further exploration may have uncovered even more intelligence. In fact, this labyrinth was the command headquarters for all operations against Saigon, Bien Hoa, and the adjacent provinces – but this fact was not discerned.

It should be noted that as 3 Field Troop was operating in an infantry support role much of their time was spent above ground defusing booby-traps, clearing paths through suspected minefields, or acting as infantrymen when in contact with the enemy. Their other engineering role was to repair roads and bridges, as well as upgrading the base facilities. It was an exceptionally varied and busy life!

The troop continued to explore any tunnels found, but as their tour of duty was coming to an end an even more important task was now taking centre stage: documenting the techniques they had developed and establishing the training that was required for the sappers who would be following their example into the darkness (on hands and knees!).

Epitaph

The danger in clearing the tunnels never went away, but the majority of the 35 sappers who died in Vietnam or the 200 who were wounded were mainly killed or injured in mine incidents of various sorts. This is a 36% casualty rate among highly skilled young soldiers. Five Military Medals (MM) and one Military Cross (MC) were awarded between 1965-1971. This is extraordinarily low for a unit that incurred such high casualties from constantly operating in a high-risk environment. Their under-recognition is more a comment on the ‘rationing’ of awards than on their operational experiences.

The following quote from Sapper Bob O’Connor in late June 1968 puts it all into perspective:

“No one is going to force you to do this kind of stuff, so if it’s not for you, ask for a transfer. But if you decide to stay though, you’ve got to believe, and I mean really believe, that you’re already dead. Tunnel rat casualty rates are ridiculously high, so it’s not too hard to believe. Once you accept you’re a dead man walking the job gets much easier. It even becomes a challenge. Nothing to do with the Army, it’s a personal thing.”

2 TP Tunnel Rat SPR Ziggy Gnoit in a Tunnel on Operation Overlord in 1971

Only one sapper was shot and killed by the enemy while clearing a tunnel, but if you are claustrophobic, or are not excited by the thrill of one-on-one combat with a bayonet or pistol in a one metre circumference confined space, in total darkness, then being a Tunnel Rat is probably not for you.

The courage, humour and tenacity of the Tunnel Rats is representative of the best characteristics of what I consider Australians to be.

My apologies for taking so long to reply, but I rarely reread my own articles. I now live in Vietnam for most of the year! I met with Tunnel Rats on their visit last year. I have randomly read many articles in Holdfast, but had not come across yours, so if you send me the link I will certainly read it.

I arranged for Jim Marett to give a presentation on Tunnel Rat operations to the OTU Scheyville Association 'Geddes Dinner' last June.

With permission I would like to use this on the day,

Thanks in advance.

Cheers

Unfortunately, I just saw your request today as I rarely reread my own articles. If you have another presentation in the future, consider this as a blanket permission to use my article

Unfortunately, my research at the time neither revealed the name of the Sergeant KIA, nor the detailed circumstances. I would certainly have named him, if i had known.

For the record: I served with Staff Sergeant Peter Gollagher both in Australia, 18 Fd. Sqn, Wacol, where he was acting SSM and in South Vietnam in 1 Fd. Sqn. I knew Peter to be a decent man and despite me being a little on what the army referred to as the 'incorrigible' side we got on well enough. As far as I was aware Peter was full-time CMF, not regular army, which perhaps encouraged him to be a little less rigid and a little more civil to the troops within his various postings.

He was my Staff Sergeant in 21 Engineer Support Troop.

He only served in 21 Engineer Support Troop not 1 Troop, 2 Troop or 3 Troop. 1st Field Squadron.

I had been in Vietnam for about ten days when he was killed.