Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. A feature of this conflict has been the significant use of trenches. This caused many nations to review their own knowledge of trench warfare and consider what this may mean for future conflicts.

The Army Battle Lab will soon be releasing a trench warfare handbook based on lessons learnt in World War I, as well as lessons learnt from the Russia-Ukraine war. This article provides some lessons from World War I which are still relevant today.

“When I came out there first, all we did in trenches was to paddle about like ducks and use our rifles. We didn’t think of them as places to live in… Now we work here all the time, not only for safety, but for health. Night and day.”

Stewart Ross, War in the Trenches

Why trenches?

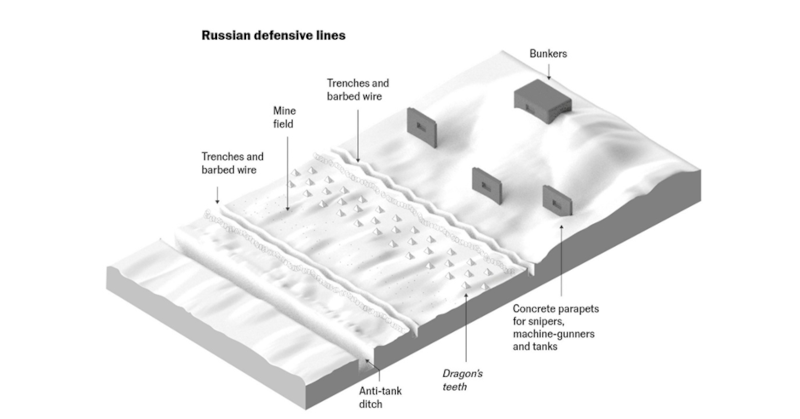

Trenches work because moving large, mechanised forces across defended territory is costly – defences like mines, bunkers, and fortifications force attackers to pay a premium in time, lives, and resources. Trenches and other defensive works help smaller or less mobile forces resist. The importance of drones (both for reconnaissance and attack), precision artillery, overhead surveillance etc., makes exposed positions extremely risky. Trenches provide cover against indirect fire, drones, and observation. Attacking entrenched positions is difficult; it's often simpler and less costly (in the short term) to dig in and defend, or to prepare heavily before attacks (bombardment, minefields, etc.). Rockets, guided artillery, and anti-tank systems mean that entrenched positions are still vulnerable, not just to massed artillery but also targeted fire. To offset this, fortifications are more layered and multi-purpose: combinations of trenches, bunkers, minefields, anti-tank obstacles, camouflage, decoys, etc.

What is happening: trench warfare in Ukraine

Both Russian and Ukrainian forces have extensively dug in: networks of trenches, bunkers, fortified lines, communication, and supply trenches are now widespread along many frontlines. The conflict has in many places shifted toward static or positional warfare – meaning frontlines move slowly and gains are measured in hundreds of meters rather than tens of kilometres. Examples of complex fortification systems include the Surovikin Line, a mutual defensive line constructed by Russian forces in southern and eastern Ukraine. In Crimea and regions where Russia expects Ukrainian attempts at counteroffensives; trench webs, anti-tank ditches, mines, camouflaged positions, and layered defences have been built.

Lessons from trenches in World War I

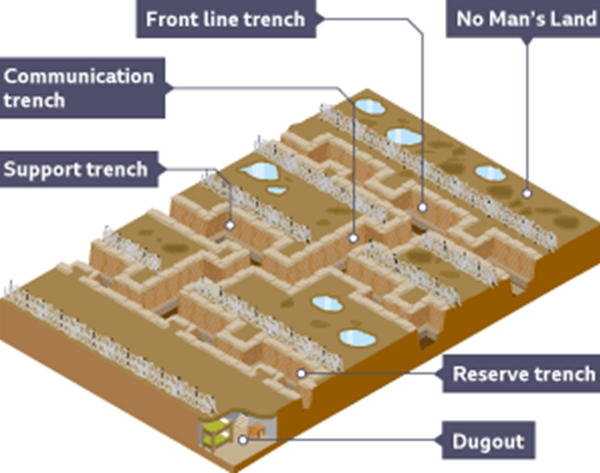

Fire trenches (front line trenches). The necessity of establishing as many continuous lines of trenches as possible has been proved in operations. Isolated supporting points are very easily detected by means of aeroplane photographs and may prove veritable shell traps. Moreover, in World War I, the absence of continuous lines was one of the reasons why the Germans were able to successfully employ their method of infiltration and were able to push small detachments into the gaps between the supporting points of the French line. A continuous trench line does not do away with the necessity for supporting points, but the latter can be easily concealed in a network of fire trenches, communication trenches, and dummy trenches.

There is a morale value in a continuous trench in that the defenders do not suffer from the feeling of being cut off, as they may do if ordered to occupy an isolated supporting point.

There must be observers in all trenches, whether advanced trenches or trenches in the first or second lines. Their duty is to warn their comrades, give the signal for barrage fire to be opened, or repeat signals made by troops in front – and for this purpose should all be provided with rockets.

Soldiers fighting in Middle East trenches during WWI.

Communications. At all costs, there must be numerous and deep communication trenches to the rear. To fail to provide communication trenches in a sector under the pretext that the sector is a quiet one and the approaches are defiladed to view, is a criminal offence. At the critical moment, these approaches are certain to be bombarded, and will then become blocked, and the troops in the front trenches will find themselves isolated. If there are no communication trenches or an insufficient number, it means that there will have to be more runners and more sending up of supplies of food and materials and possibly reinforcements, all of which will entail increased losses.

‘The so-called trenches were only a few inches of soil scratched up with our entrenching tools we carry and the soil heaped up in front. We all formed up in line and hurriedly dug away before we had 12 inches of trench dug. We had to repel an attack. And so it was hour after hour – dig and fire. We kept this up for days.’

Fremantle to France, 11 Battalion AIF 1914-1919

Australian Pioneers building a communication trench. Communication trenches led up to the front

Relief of trenches

Taking over. If possible, it is always best for an officer and company quartermaster sergeant to go on some hours ahead and take over the trenches – the officer to see the boundaries of the company lines and where platoons are situated, special points better seen by day etc.; the sergeant to take over trench stores. Your platoon, having reached the fire trenches, will stand-to until you have taken over properly and posted your sentries.

Some points the officer and company quartermaster sergeant must know:

- Number of bays and number of soldiers to fill them.

- Number of sentries day and night and number of soldiers to remain awake.

- Hours of ‘stand to’ day and night.

- Enemy’s lines and range to same.

- Any patrol to be sent out and warn companies on right and left when sending them out.

- Enemy’s artillery and trench mortars and machine guns, where they fire from, and usual hours.

- Any enemy’s favourite sniping posts or any dangerous place in trench.

- Where soldiers can be put in a bombardment to relieve fire bays.

- How much small arms ammunition is in reserve and where it is – platoon reserve, company reserve, and battalion reserve.

‘So great was the damage effected by hostile fire that in many parts of this track, mud thigh-deep had to be traversed, while the pitch-dark night, consistent rain, and ceaseless shelling all assisted to prolong to eight hours the period of approach. So, between 2 and 3 am, relief was carried out by these mud-covered troops, none of which had succeeded in reaching their trench without at least one fall.’

The Forty-third Battalion

Example of a World War I trench system

Duties of section commander. On arrival in trench:

- Parties to go into their proper bays.

- Bay commanders thoroughly understand their duties.

- Each soldier can fire at the bottom of their own barbed wire.

- All know what to do on alarm or warning of gas.

- Dangerous places in trench are marked and soldiers warned.

- Periscopes are ready for use at daybreak.

- Keep in touch with sections on their right and left.

Trench discipline

- At night, all firing should be over the parapet and not through loopholes.

- Officers are not to fire, but to direct the fire of the soldiers.

- An observer must always be in the trenches and should be provided with glasses and keep a written record of what they see.

- Continuously be on the lookout of snipers. Never let the soldiers walk about exposed.

- See that proper rest hours by day are observed by the soldiers and that quiet is maintained. Sleep is essential.

‘The other five Turks threw bombs into the trench, slightly wounding three men, and then fled to the safety of their own trenches. Not a shot was fired at them, which speaks highly for the discipline of the troops, who refrained from opening up on such a tempting target.’

The story of the 17th Battalion AIF, 1914-1918

Patrols

- All movement must be carried out with some definite object in view, and every soldier in the patrol must be in full possession of the objective.

- All movement must be slow and gradual; by bounds from point to point, from cover to cover.

- All movement must be carried out according to the first principles of protection; advance scouts, flank scouts, main body scouts, rear scouts.

- All must be in full knowledge of the movements of other friendly patrols and scouts.

- All must be fully informed of the hour of starting and returning, and the point to which to send reports.

- All must be fully informed and trained in the giving of special signals of recognition.

- All letters, papers, badges of rank, and other articles which might give information to the enemy must be left behind.

‘Our patrol greatly underestimated the enemy’s vigilance, for the men did not crawl over ‘no man’s land’, but simply walked across in a stooping posture, so that Fritz, immediately he detected their movements, waited and allowed them to come quite close up before opening fire.’

The Forty-First

Snipers

During a turn of duty, the following lessons were learnt:

- Two soldiers were necessary to each post; one to shoot, the other to observe; therefore, two loopholes fairly close to each were necessary.

- To avoid disturbance of the natural contour of the ground, the loopholes had to be shored up with timber as work proceeded.

- The officer IC snipers and the snipers would have to be attached to the battalion headquarters and struck off all other duties while in the trenches if delay and confusion was to be avoided.

- Regular reliefs for each post were necessary if a constant watchfulness from dawn to dark was to be obtained.

‘On one occasion, we were much troubled by a well-placed sniper. Like snakes, two Australian boys crept from the trench and crawled out of sight through the scrub. All unconscious, the Turk continued his rifle practice until a double report rang out, and our two men appeared, waving the sniper’s hat, their equivalent of a scalp. After that we had comparative peace.’

Imperishable ANZACs

A spotter would use a periscope to scan for targets

Trench feet

Precautions against trench feet. Some essential things undoubtedly are:

- A good supply of dry socks to change each day, and if necessary two changes. Socks should not fit tightly.

- Not lacing the boots too tightly. Boots should be removed for a short time daily and should fit easily.

- Cleaning, drying and oiling the feet thoroughly after taking off wet socks and before putting on dry ones. Both the feet and legs should be rubbed with oil daily.

- Circulation should be kept up by a few moments of occasional exercise, particularly after soldiers have been stationary while on duty.

- Plenty of hot food and hot drink.

- Dry trenches.

- Inspections twice daily.

‘Yet for all the foresight and care expended, [we] could not entirely ward off the dread of the soldier, trench-feet. Men came … limping painfully in boots that had to be cut from their feet to disclose the swelling and dull discolouring of incipient frost-bite.’

The Story of a Battalion [48th]

Conclusion

This article provided a small collection of World War I trench warfare tips. To read more on this topic, as well as Ukraine trench warfare experiences, Army Battle Lab is preparing an Insights from Trench Warfare handbook. Once published, soldiers can view it via the Defence Protected Network. Search for ‘Army Lessons portal’, and then open ‘Other Lessons Publications’ to see if it has been released.