The team at The Cove remembers those who have gone before us, particularly those who have given their lives in the service of the nation, and thanks all members of the profession of arms for their service. Lest we forget.

The 25 April 1915 is a date etched in Australia's history. Some see it as Australia's 'baptism of fire' and 'the birth of nationhood'. Its anniversary is commemorated across the country each year as Anzac Day. To many this is Australia's most important national day.

Initially, Anzac Day was a mark of respect for those who served and sacrificed their lives in the Great War. However, in the years since WWI Australian troops have answered the call in conflicts across the globe. As a result, the date has become the day on which the nation remembers those who have served and those who made the ultimate sacrifice in all the conflicts that Australia has participated in.

Anzac Day

In 1915, the British planned to secure the heights overlooking the forts guarding the narrow straits at the entrance to the Sea of Marmora. The purpose: to silence them and allow the French and British Navy to proceed to Constantinople (now Istanbul) and, by a show of force, convince the Turkish Government to capitulate and to come to the side of the Allies.

Image 1: Allied Forces landing map (DVA)

The plans did not bear fruit and what ensued was a tremendous series of battles over the next eight months. Both sides suffered horrendous casualties amongst the many ravines and gullies of that rugged battleground on which the Anzac tradition was formed and that has become the benchmark for standards of courage, mateship and determination that has set an example for all Australians to follow.

In the dark before the dawn on 25 April 1915, battleships, destroyers and troopships approached the Turkish coast where the Australians and New Zealanders were to land. The 3rd Australian Brigade (4,000 men) was to be the covering force, with other brigades to come ashore throughout that day and the next.

Image 2: Men of the 8th Battalion

Leaving the ships, the Australians were towed in boats before rowing the final distance to the beach. In the darkness the boats landed in the wrong positions. Once off the beach the men faced high hills, cliffs and ravines. The terrain was not what they had been told to expect, but it provided some protection.

At first the Australians coming ashore were confronted only by a thin line of Turkish defenders and the main beach was swiftly taken. Around them the hills provided some protection but, covered with the thick prickly scrub, these proved a formidable barrier to further advance.

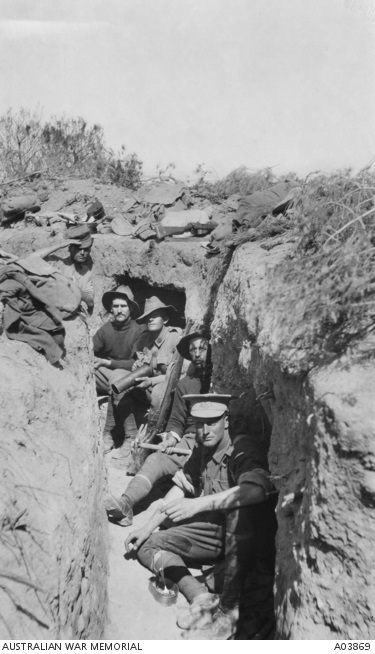

Image 3: A rough firing line formed by the 3rd Battalion at "The Death Trap", an exposed position near Lone Pine

By 8 am, some 8,000 men, including the main force, were ashore. The beaches were never the bloodbath that some writers and artists have depicted. Most casualties occurred during the fighting in the hills above the beaches, with the Turks determined to prevent the capture of the high ground. Scrambling up the hills, the Australians took the first ridges, but their objectives were still far off. The fighting in the hills and scrub became fierce, and this is where most of the day's casualties occurred. By mid-morning the Turks had rushed up reinforcements. They had orders to fight to the death. The Turks met the Australians on the ridges and fierce fighting followed, often at close range and sometimes with bayonets. Many positions were lost to these heavy enemy counter-attacks. The Turks held the main ridge and the heights, while the ANZACs clung to a narrow three-kilometre strip of hills overlooking their landing beaches. As the day went on, it became evident the task was impossible. Evacuation was ruled out, so the men were told to consolidate. The order came: 'There is nothing for it but to dig yourselves right in and stick it out.' The front line did not change much for the next eight months.

Image 4: Wounded coming down the valley

During the day the medical services were overwhelmed. The suffering of the wounded was pitiful; many men died on the beach, and it is estimated that hundreds more lay in the hills out of the reach of help. Most notably, there were inadequate arrangements for the critically wounded, who could not be taken back to the ships until after all the troops and stores had been landed. It was early evening before boats became available; many of the maimed and bleeding were sent off in filthy barges.

No one knows for sure how many Australians died on the first day, perhaps 650. Total casualties, including wounded, must have been about 2,000. This news trickled in to the Australian newspapers. Even a month after the landing, only 350 deaths had been acknowledged.

Origins of the term 'ANZAC'

ANZAC, an acronym for the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps, was used by the clerks of General Birdwood’s staff at his headquarters in Shepheard’s Hotel in Cairo, Egypt.

The word ANZAC was approved by General Birdwood as the code for the Corps when the word was proposed by a Major CM Wagstaff. It is thought the suggestion came from a Lieutenant AT White of the Royal Army Service Corps. It is recorded in the official history that 'it was some time before the code word came into general use, and at the Landing (on 25 April 1915) many men in the divisions had not heard of it'. After the landing, General Birdwood gained permission to use the name for the area occupied by the Australian and New Zealand Forces.

Military Remembrance Artefacts

The Ode

The Ode is the fourth stanza in the poem, 'For the Fallen', written by the English poet and writer Laurence Binyon which was first published in London in the Winnowing Fan; Poems of the Great War in 1914. The verse, which became the League Ode, was already used in association with commemoration services in Australia in 1921.

'They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old;

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.'

The Last Post

In military tradition, the Last Post is the bugle call that signifies the end of the day's activities. It is also sounded at military funerals to indicate that the soldier has gone to his final rest and at commemorative services such as Anzac Day and Remembrance Day.

Reveille and the Rouse

Reveille, from the French word ‘reveillez’, meaning to ‘wake-up’, was originally played as a drum beat just prior to daybreak. During the Anzac Day Dawn Service, the Last Post is sounded followed by a minute of silence. At the Dawn service, the silence is broken by the Reveille.

Rouse, commonly called 'short reveille' the Rouse is a bugle call most familiarly played at military funerals and services as well as at Remembrance ceremonies in the Commonwealth realms. The Rouse is used after the minute silence during daytime commemorative services.