Introduction: A Failing Situation

Brisbane is burning. The Sydney CBD lies in silence, occupied and draped in foreign flags. In just twelve days, the bulk of the Australian Defence Force has been overwhelmed, bypassed, or destroyed. Ports are seized, communications are severed, and political leadership is either in exile or captured. The enemy owns the airwaves, controls the cities, and patrols the highways. And across the suburbs, towns, and farms, there is silence. No resistance. No coordinated pushback. No plan. The Australian people were never trained for this.

There was no stay-behind force, decentralised militia, or doctrine for irregular warfare on home soil. With the regular Army either destroyed or pushed into isolated bushland redoubts, the enemy consolidates rapidly. They move fuel and food via road and rail unchallenged. They establish civil control through soft power and coercion. Without organised sabotage or intelligence gathering, the invaders operate unopposed behind their own lines. The population, afraid and confused, is told to comply – or be crushed.

Australia’s geography was once considered its greatest defence. But in the twenty-first century, distance alone is not enough. Cyber strikes paralysed infrastructure before the first boots landed. Drone surveillance blankets key terrain. Enemy forces use Australia’s own roads, rail, and communications systems against it. There is no rear area – only occupied ground.

What is missing is a citizen force trained in resistance, prepared to deny the enemy safe occupation. Not a standing army. Not weekend reservists. A civilian-based, cell-structured, irregular force designed not to win conventional battles but to prevent the consolidation of control. Their mission would not be to hold territory, but to make it ungovernable.

This is not an incitement to vigilantism or unsanctioned militias. It is a structured, state-authorised framework for national resilience. The concept is grounded in law, guided by ethical oversight, and designed to operate in concert with existing Defence policy, ensuring civilians can defend their communities under controlled, accountable conditions.

This essay proposes the need for a 21st-century Citizen Militia Force: a modern, invisible backbone of national defence. A deterrent based not on mass firepower but on unpredictability, disruption, and total national resilience. The force must be built before the first shot is fired because once the enemy is here, and no one is ready to fight, they have already won.

History of Australia’s Citizen Military Forces

Early Colonial Militias (1788-1901)

In the early years of European settlement, the defence of Australian colonies primarily relied on British garrisons.[1] However, as the colonies grew, local militias were formed to address specific threats and reduce dependence on British forces. These militias were composed of local volunteers and were instrumental in maintaining internal security and responding to external threats.

Following the Federation of Australia in 1901, the various colonial forces were amalgamated into the Commonwealth Military Forces (CMF).[2] This unification aimed to create a cohesive national defence strategy. The CMF consisted of both permanent troops and citizen soldiers, emphasising the importance of a trained civilian reserve, ready to support national defence when required.

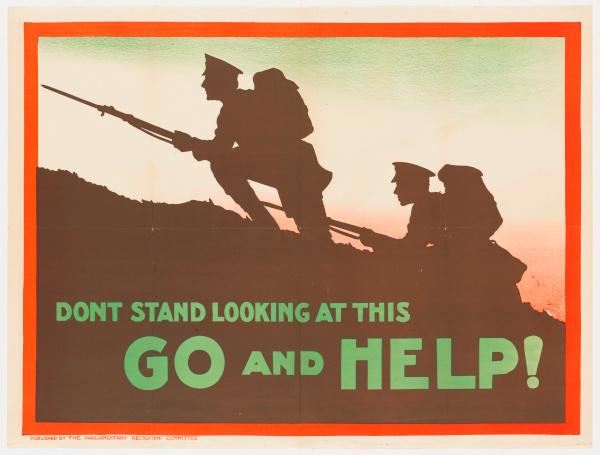

With the outbreak of World War I (WWI), Australia faced the challenge of raising sufficient forces for overseas service.[3] While many volunteered, the declining enlistment numbers led to intense debates over conscription. Two referendums were held in 1916 and 1917, both of which resulted in the rejection of compulsory overseas military service. This period highlighted the nation's reliance on volunteer citizen forces and underscored the complexities of mandating military service.

Post-WWI, the CMF underwent several transformations, reflecting the nation's shifting Defence priorities. The force was restructured to balance a small permanent military and a more substantial citizen component, ensuring that Australia maintained a ready and capable reserve force without the financial burden of a large standing army.

The threat of invasion during World War II (WWII) led to the establishment of the Volunteer Defence Corps (VDC) in 1940, modelled after the British Home Guard. Initially composed of WWI veterans, the VDC's role expanded to include training for guerrilla warfare, local intelligence gathering, and static defence of their regions.

By 1942, the VDC had grown to 45,000 members, reflecting the nation's commitment to involving its citizenry in homeland defence[4].

After WWII, the CMF was restructured and eventually renamed the Australian Citizen Military Forces (ACMF). In 1980, it became known as the Army Reserve, continuing the tradition of maintaining a trained civilian force ready to support the regular army.

This evolution marked a shift towards integrating citizen soldiers more closely with the nation's overall defence strategy.[5]

What the 21st-Century CMF Is – and Is Not

The Citizen Militia Force (CMF) is not a rebranded Reserve, a Ready Reserve revival, or a state-sanctioned home guard in uniform with parade schedules and annual camps. It is a latent, decentralised resistance capability embedded within civilian society, trained not to support government operations in peacetime but to resist occupation when the nation is on its knees.

Where the Army Reserve is designed to reinforce conventional military operations, the CMF would serve as a force of disruption. Its role would begin after the front lines collapse, when the command structure has fragmented, and the invader believes the country is subdued. The CMF would ensure it is not.

This force is not made to win set-piece battles. It is made to harass, sabotage, report, and survive. Organised into small, independent cells, it would be invisible until activated. Its purpose is to make the cost of occupation unacceptably high, through resistance, not defence.

This isn’t about duplicating the ADF but building the layer beneath it. The layer that keeps fighting when everything else is gone. Not soldiers in barracks but citizens in shadows. That’s the role of a 21st-century CMF.

CMF Team Layout and Required Capabilities

The foundation of the CMF must be built around small, compartmentalised cells – agile enough to operate independently, resilient enough to survive isolation, and disciplined enough to function without central command.

Each cell would ideally consist of four to six members, forming the smallest operational unit. Multiple cells could be grouped into loose platoon-level networks, but always with a focus on operational security and decentralisation.

Each CMF cell must be trained across a core spectrum of irregular warfare[6] tasks. It must be lean, self-sufficient, and focused on effects, not doctrine. This is not a standing force but a latent insurgency-in-waiting, trained and embedded before the first shot is fired.

How to Achieve This Force

Building a 21st-century Citizen Militia Force cannot rely on conventional recruiting or open enlistment. The CMF must be discreet in its formation, legal in its existence, and practical in its training.

Mobile Training Teams (MTTs). The backbone of CMF preparation would be Mobile Training Teams – small groups of qualified instructors embedded in civilian communities. These teams would deliver modular, dual-purpose training in survival, bushcraft, communications, field medicine, and irregular tactics. Delivered under the guise of disaster resilience or civil emergency readiness, this training would build core skills without signalling intent.

Pre-Positioned Resources. Strategically dispersed across rural and urban terrain, caches would include encrypted radios, first aid kits, water purification tools, power banks, basic demolition materials, and written guides on communications and sabotage. These must be concealed, recoverable, and managed under secure protocols.

Legal Frameworks. A legislative foundation must be laid in peacetime. The CMF must be authorised under national emergency or martial law provisions, with clear activation triggers and legal protections. This protects volunteers from prosecution and ensures state oversight when required.

Community Engagement. The CMF would quietly draw from veterans, first responders, survivalists, and trusted civilians, particularly in rural, remote, and disaster-experienced communities. These are Australia's natural defence assets, already trained in leadership, logistics, and self-reliance.

Mobilisation. Mobilisation is more than just moving troops – it prepares an entire society for survival. Both Finland and Switzerland offer enduring models of civil resilience, military preparedness, and national identity unified under law.

Lessons from Finland and Switzerland

Australia is not the first nation to consider how civilians might be trained to resist in the event of occupation. In fact, models already exist that demonstrate how such a force can be built without compromising a professional military structure.

These countries recognised early that a conventional military could not hold every town or protect every home. They built decentralised, trained, and trusted civilian frameworks to delay, deny control, and increase the cost of occupation. If Australia seeks to match that level of resilience, it must develop a model of mobilisation that includes, not excludes, its civilian population.

Finland: Total Defence Doctrine. Finland’s national defence model rests on the belief that every citizen has a role in the country's survival.[7] Military training is widespread, and the concept of “Total Defence” includes not only the army but the economy, civil service, infrastructure, and the population itself.

Every citizen knows they may be called upon to resist – militarily or otherwise.[8] The psychological effect is clear: Finland is not just defended by an army, but by a society.[9]

Switzerland: Cold War Stay-Behind Forces. During the Cold War, Switzerland maintained a classified network of stay-behind units. These civilian-based resistance groups were trained, equipped, and prepared to conduct sabotage, intelligence collection, and unconventional warfare in the event of Soviet invasion.[10] Their very existence was a deterrent – proof that occupation would never lead to peace.

What Australia Can Learn. These models show that resistance is not reckless, but rather deliberate, trained, and legally grounded.[11] For Australia, the lesson is simple: a prepared population, trained in irregular tactics and supported by civil infrastructure, can offer a strategic advantage no adversary can ignore.[12]

Positive Outcome Scenario

The enemy lands, but this time the country is not silent.

They seize the ports only to find fuel dumps already scorched and rail hubs disabled by targeted sabotage. Convoys are ambushed on highways by unknown assailants. Bridges collapse under pressure-activated charges. Civilian comms networks are jammed, but encrypted shortwave messages still flow – coordinated and accurate. Local informants vanish before they can be traced.

In the bush, hill country, and outer suburbs, the CMF begins to move. Not in uniform, not in formation – but with knowledge, intent, and discipline. Field medics treat wounded ADF personnel. Intercepts of enemy transmissions are relayed through covert channels. Messages of resistance spread via burner networks, spray-painted slogans, and encrypted FM bursts. The invader’s belief in quick control dissolves into paranoia.

ADF units that once operated in isolation are now resupplied from pre-stocked caches. Enemy soldiers begin wearing civilian clothing in fear. Reprisals against the population backfire, turning locals into collaborators with the resistance.

The CMF does not hold ground; it denies control. Its impact is psychological as much as tactical. The occupation slows, then falters. International support builds. The invader’s advantage – initiative, speed, surprise – is lost.

Australia has not surrendered. It has adapted.

National Pride and Warrior Culture

Australia has always been a nation shaped by struggle against harsh landscapes, isolation, and impossible odds. That struggle forged a culture of grit, adaptability, and quiet defiance.[13] From the Gallipoli cliffs to the Kokoda jungle, from the frontiers of colonial resistance to the wire fences of Long Tan, Australians have never accepted the idea of easy surrender.

This is not just military history; it is national identity.

A Citizen Militia Force would not be an invention. It would be a revival. A rekindling of the spirit that built this country: the shearer who joined a light horse regiment, the farmer who trained his sons to shoot, the Aboriginal tracker who knew the land better than any map. These are not myths – they are precedents.

In a time when national service is rare and many believe the next war will be fought in cyberspace, we forget that wars are still won (and occupations resisted) by people who refuse to be broken. Warrior culture is not about violence. It is about resolve, about the sacred duty to protect what is yours.

The CMF embodies that spirit. Not for glory. Not for power. But to ensure that the next invader finds not victims – but warriors.

Counterarguments and Labelling

Critics will argue that this concept is extreme, that it risks vigilantism, militarises civilians, or invites dangerous parallels to paramilitary groups seen in other countries. They will say the CMF could blur lines between lawful defence and unlawful insurgency, that such a force, if activated, would be branded as terrorists, not patriots.

They are not wrong to ask these questions. But they are wrong to ignore history.

Every modern resistance has been called unlawful by its occupier. The French Resistance, the Polish Home Army, Ukrainian partisans – each one was labelled a threat to "order." The enemy will always call rebellion terrorism. That does not make it wrong. It makes it necessary.

The difference lies in preparation, legitimacy, and discipline. A CMF is not a rogue militia. It is a state-sanctioned fallback – activated only in the absence of sovereignty. It would train under strict guidance, with clear legal triggers for mobilisation and firm rules of engagement tied to national law.

Conclusion

Australia’s defence strategy cannot rely solely on professional forces and conventional thinking. In an age of hybrid threats and strategic uncertainty, our greatest vulnerability is the assumption that someone else will defend us. The truth is, if invasion or occupation ever comes to our shores, the nation will survive not because of its weapons but because of its will.

A Citizen Militia Force is not a relic of the past; it is the missing link in our national defence posture. It draws from our history, reflects our culture, and answers a strategic gap that neither the Regular Army nor the Reserves were designed to fill.

We do not need mass mobilisation. We need smart, decentralised preparation. Other nations – like Finland and Switzerland – have shown that mobilisation must extend beyond uniforms and command structures. It must include the civil domain, with trained, empowered civilians forming a prepared population.

This model of national mobilisation should inform Australia’s approach to modern resilience. We need citizens trained to resist, disrupt, and endure – not just to fight but to deny control. The time to build this capability is not during a crisis. It is now – while we still have the means, the freedom, and the choice.

Because when the enemy arrives, it will be too late to start training. And too late to start believing that our citizens could have been warriors.

End Notes

[1] “1788 to 1810 - Early European Settlement,” accessed April 8, 2025, https://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/about/Pages/1788-to-1810-Early-Europe….

[2] “Colonial Period, 1788–1901 | Australian War Memorial,” accessed April 8, 2025, https://www.awm.gov.au/articles/atwar/colonial.

[3] “Conscription during the First World War, 1914–1918 | Australian War Memorial,” accessed April 8, 2025, https://www.awm.gov.au/articles/encyclopedia/conscription/ww1.

[4] “Australia under Attack: Australia’s Home Guard | Australian War Memorial,” accessed April 8, 2025, https://www.awm.gov.au/visit/exhibitions/underattack/mobilise/guard.

[5] “Australian Military Forces,” in Wikipedia, April 23, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Australian_Military_Forces&o….

[6] Andrew Maher, “A Framework for Irregular Warfare,” n.d.

[7] “Does Finland’s ‘Total Defence’ Doctrine Hold Lessons for Australia? | Lowy Institute,” accessed April 8, 2025, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/does-finland-s-total-defe….

[8] “Does Finland’s ‘Total Defence’ Doctrine Hold Lessons for Australia?”

[9] “Finnish Defence Forces,” in Wikipedia, April 7, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Finnish_Defence_Forces&oldid….

[10] “Building a Stay-Behind Resistance Organization: The Case of Cold War Switzerland Against t,” National Defense University Press, accessed April 8, 2025, https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Media/News/Article/1220620/building-a-stay-beh….

[11] “The Conceptualization of Irregular Warfare in the Indo-Pacific Region,” accessed April 8, 2025, https://irregularwarfarecenter.org/publications/research-studies/the-co….

[12] Defence Mobilisation Planning Comparative Study: An Examination of Overseas Planning (RAND Corporation, 2021), https://doi.org/10.7249/RR-A1179-1.

[13] “Cove Podcast | Warrior Culture | The Cove,” accessed April 9, 2025, https://cove.army.gov.au/article/cove-podcast-warrior-culture.

Still, a thought provoking concept, and nicely put together. Thanks and keep writing.

In days of home guard wea1pons were supplied. Amunition dispensed.

Imagine today arm half the civilian males.

And much wojld bd libdrated sold and be

turnedd inwards in short order.

I mmow as a young boy k. The uk by qor5 i bad a respectable arsenal of dmall arms wkth several thousand rounds. Half a cwt of very good black powder. Home made.

Very effective turned into pipe bombs.

And even mini rocket projectiles. As the local neighbouhood knew from my ,'Fireworks'. Small arms acquired from

friends from mlitary.

Alongwith ammo. Almost sorry the war ended.

(All sides) remain blissfully unaware of the content of this document- I would fully support the raising of a civilian response force that could also be used in time of natural disaster to further assist the community in which they reside

Having just read "No Higher Priority", adaptation of the 'Swiss model' to Australia's circumstances has been much on my mind.

The burning question is by what means can we re-enliven political and popular support for such a force.

I'm not yet too old for that, but I have zero confidence in the Communist/Marxist/Stalinist Federal and State Labour Governments to actually implement this, more fearful of an armed populace, than any potential invader, and after the drastic treatment of the population during the all too obviously planned and executed COVID hoax, and who in their right mind would really sign up for militia duty, knowing how their respective Governments treated them before, are treating them now, and may in the future?

I’m not across the Defence Act, but this could possibly be done without changing the law which would need an act of Parliament. As the writer implies setting it up be done quietly and below the radar and if as I suspect it could be done with the letter of current law, it could done administratively without needing to involve Parliament at all.

As to who to recruit, as I know from personal experience many otherwise suitable applicants to the Army Reserve fall short one way or another. These could be a source of potential recruits along with categories already mentioned.