The conflict environment is undergoing considerable and rapid change. More armed groups have emerged in the past six years than in the entire previous six decades. Warfare is being conducted in urban centres among civilian populations who represent the most frequent casualties. Ongoing violations of the law, sometimes as part of a deliberate military strategy, are generating an exponential growth in humanitarian needs whilst simultaneously making work difficult for humanitarian actors. Although we’ve seen a decrease in the number of international conflicts waged directly between State parties, internal and protracted situations of long-term violence continue to rise. The conflicts in which the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) operates are increasingly long-term, fragmented and complicated. As a humanitarian organisation originally created to respond to emergencies, we have now been on the ground for an average of 36 years in our ten largest operations. Changing dynamics of violence have brought ICRC delegates closer and closer to the fighting, and made their working conditions ever more dangerous. These tensions put pressure on our traditional ways of working as a neutral, independent and impartial actor.

Mosul: The ICRC donates body bags to Mosul civil defence directorate.

ICRC / Ibrahim Sherkhan

Security and access: relying on principles

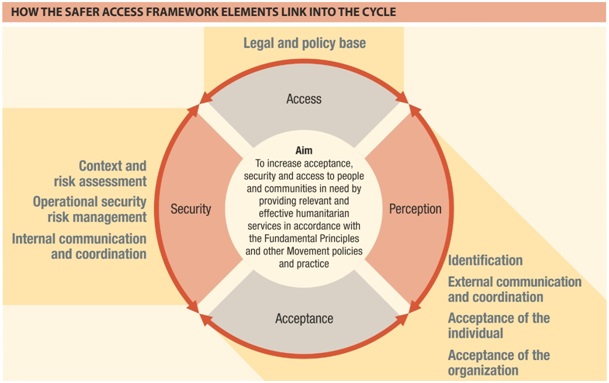

Fundamentally, security for the ICRC is not a matter of physical protection. Our staff never operate with armed escorts or protective equipment and do not carry any light weapons for personal defence. Instead, we rely on a 'perception based security'. That is, ICRC must be, and also must be perceived by combatants to be, neutral so that the organisation is not considered as a threat. This means we must maintain a constant dialogue with all authorities and arms carriers controlling territory; both traditional State forces and also the variety of non-State actors present in contemporary conflicts. Through these dialogues the ICRC emphasises our neutrality, impartiality and independence in order to be accepted and allowed to operate in an area, creating access to affected populations. These principles then continue to underpin the action we undertake for those affected populations, thereby reinforcing perceptions of the ICRC and creating a loop of security.

ICRC / Safer Access Framework (SAF) diagram of perception based security

Establishing dialogue with the appropriate people presents particular challenges in the context of non-State armed groups, which can have weak, shifting or indistinguishable chains of command. Even just identifying which are the relevant armed groups can be difficult; in several regions we are seeing in excess of ten parties to a conflict. A consistent approach is therefore essential. As frontline negotiators, ICRC delegates must keep abreast of fluid situations and be sensitive to subtleties which may signal the morphing or fragmentation of a group.

Colombia: An ICRC employee speaks to members of the National Liberation Army (ELN) armed group about the principles of the international humanitarian rights and the obligation to respect the lives of the civilian population, health personnel, and the sick or wounded.

ICRC / Juan Arredondo

Denial of access: testing impartiality

Of course, relying on the acceptance and consent of all parties means that the ICRC may find itself unable to operate when access is denied by the authorities. Although the Geneva Conventions and their Additional Protocols require parties to a conflict to allow and facilitate the delivery of humanitarian relief, and our new Commentary to the First Geneva Convention has shown that in reality no State should ever refuse access of the ICRC when providing humanitarian relief, there are situations in which parties to a conflict do explicitly refuse or indirectly prevent access. This challenges the ICRC’s commitment to impartiality: how can we ensure that we are delivering assistance to those who need it most when our operations are directed by the geographic scope of our access?

This has been an ongoing issue in the context of Syria.

However, compromising our principles by attempting to conduct cross-border assistance in the absence of consent would undermine the effectiveness of our overall operations. Such is the value of our reputation that in some places we are the only international organisation which is able to operate. This is the case in some parts of Myanmar, including Rakhine state; in Sri Lanka in 2009 during the final government offensive; and in Afghanistan it has been observed that ICRC has been the only organisation able to maintain a continuous dialogue with the Taliban.

Merging military actions and assistance: neutrality and independence under fire

The politicisation of humanitarian assistance continues to be an issue from which the ICRC strives to distance itself. Linking humanitarian action with political and military agendas has been a recurrent theme in the Afghan and Iraqi contexts, as parties aim to 'win hearts and minds'. For a period of a few years around 2001, neutrality as a guiding principle of humanitarian action was roundly rejected by most actors in Afghanistan and the ICRC’s approach was viewed by some as outmoded. One party to the conflict linked assistance and aid organisations with a counter-insurgency campaign, and the other rejected and targeted aid organisations as agents of an imperialist West. In particular, the murder in 2003 of ICRC water engineer Ricardo Munguia in Afghanistan cast doubt on whether the perception of ICRC neutrality could be maintained in this polarised context. The ICRC rebuilt its image after that devastating attack, and those opinions were changed when the ICRC’s demonstrated neutrality and independence were shown to assist all sides to the conflicts. Yet the underlying suspicion and perception remains in some quarters. The painful decision to scale down operations in Afghanistan last year after seven ICRC staff were killed, as well as recent announcements by the Taliban withdrawing security guarantees, highlight the gravity of the continuing challenges to operating in such contexts.

In the first six months of 2018 alone, over 300 aid workers were killed, kidnapped or arrested and many more local responders have been targeted. A number of deliberate attacks on the ICRC, turn the 'classic' security environment (where the main risk is of finding oneself at the wrong place at the wrong time) on its head and call into question the fundamental basis of our security system.

While many other aid organisations abandoned a neutral stance, the ICRC has persevered, allowing it to continue and expand its work protecting victims and providing them with assistance particularly in areas where shifts in territorial control excluded actors associated with one side of the conflict.

Neutrality and independence allows the ICRC to achieve delicate humanitarian aims, such as evacuating the wounded and visiting detainees; supporting the retrieval of mortal remains; serving as a neutral intermediary during hostage crises (such as during the recent Boko Haram releases in Nigeria); and, above all, maintaining dialogue with all sides when there are allegations of abuses against civilians.

Panama City, La Joya prison: ICRC staff evaluates the living conditions of the detainees.

ICRC / Brenda Islas

The future of principled action

Of course, maintaining fidelity to the fundamental principles is not the same thing as saying that the ICRC should not adapt and adjust its approach to suit the changing nature of modern conflicts. Indeed, the ICRC is very conscious of the need to ensure that its action remains effective and appropriate.

To this end, the ICRC recently conducted a landmark study, with significant input from the Australian Defence Force, to better understand the most effective ways of influencing the behaviour of militaries and armed forces in conflict. The 'Roots of Restraint in War' study examined the sources of influence on the armed forces and how formal and informal norms condition the behaviour of soldiers. It examined two State armed forces (the Australian and the Philippines Armies) and six armed groups, ranging from those with a highly decentralised structure to those embedded within their communities. The study’s findings provide a framework of analysis for humanitarian actors, including the ICRC, to identify the approach best suited to a group’s particular structure and socialisation mechanisms, with the aim of promoting restraint during armed conflict.

Many of the findings were also quite surprising, and represented something of a shift from the ICRC’s previous thinking and practice. This kind of research shows that we must continue to innovate and look for new ways to engage with different actors in conflict. However, it is important to note that none of the study’s findings called into question the continued relevance and efficacy of the fundamental principles. They are key to ensuring the security of our personnel in the field, and maintaining our access to the various parties to a conflict and, more importantly, to the victims. If our humanitarian action is not impartial, neutral or independent we cannot hope to win the trust of the parties, or of the people we are trying to assist.