Operation Compass in 1940-1941 in the western desert of Egypt and Cyrenaica, as well as Operation Al-Fajr in 2004 in Fallujah, provide excellent case studies where methods of communication ensure the enemy’s weakness is understood and targeted while avoiding enemy strengths. In these examples, communicating a plan effectively means conducting rehearsals, establishing mission command, and circulation on the battlefield. In doing so, commanders can exploit opportunities presented to them because effective communication of the plan enables reconnaissance pull. By achieving this tenant of manoeuvre, commanders and their teams are ready to achieve dynamistic, speedy and cooperative actions in uncertain operating environments with technology that continues to change war’s character.

Operation Compass, commanded by LTGEN Richard O’Connor, was one of the first offensive actions by Allied forces in WW2. The operation resulted in an outnumbered mobile Allied Western Desert Force (WDF) defeating the Italian 10th Army. O’Connor’s significant success in the operation was due largely to his ability to communicate his plan through rehearsals, mission command, and battlefield circulation.

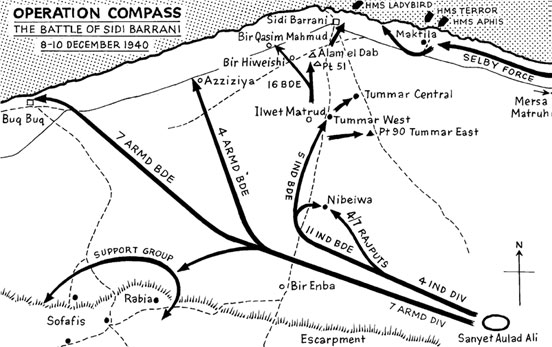

Key to the WDF’s success was their construction of mock-up of enemy positions, which were built using intelligence gathered from motorised and aerial reconnaissance. O’Connor’s communication and reinforcement of the plan during rehearsals on these mock positions ensured that subordinate elements knew the likely disposition of the enemy in Nibeiwa and where to target weaknesses.[1] A shared understanding was also established between the combat arms as a result of the rehearsals, as armour, infantry, and artillery units manoeuvring together could ensure that the WDF was able to maintain momentum in the attack and exploit the opportunities of effective reconnaissance and combined arms.[2]

Mission command espoused by O’Connor facilitated the effective communication of his plans. Shared intent between him and his subordinates was an ideal replicated throughout the chain of command. His mission-oriented orders were the standard often required due to limited direct communications post-H hour.[3] Plus, the development of shared procedures allowed co-located RAF and WDF headquarters to employ capabilities more effectively.[4] Motorised and mechanised ground forces exercised this with direct coordination of air support against Italian forces.[5] Commonly understood information requirements ensured reconnaissance patrols from different elements identified the weakest areas for combined arms advance.[6] Moreover, the WDF’s understanding of their commander’s intent to cut off and destroy allowed them to rout the Italian 10th Army in the vicinity of Beda Fomm.[7]

O’Connor’s subordinate elements leading the advance against enemy positions were often briefed face-to-face before the commencement of their offensive actions. O’Connor achieved this coordination by ranging the battlefield and applying himself to the main effort to ensure support effects were coordinated and understood.[8] His willingness and ability to push forward ensured that divisional commanders were delivered current information in order to exploit opportunities.[9] Before attacks on Bardia and Tobruk, he issued his commander’s intent and guidelines face-to-face, resulting in successful deliberate assaults against the Italians.[10]

Similarly, Operation Al Fajr’s ground manoeuvre, commanded by LTGEN Richard Natonski, was a key offensive action in retaking the city of Fallujah during the Iraq war in 2003.

Similarly, Operation Al Fajr’s ground manoeuvre, commanded by LTGEN Richard Natonski, was a key offensive action in retaking the city of Fallujah during the Iraq war in 2003.

The 1st Marine Expeditionary Force (1MEF) cleared entrenched insurgents from a well-planned urban defence.[11] Despite being physically dislocated prior to the operation, 1 MEF’s planning was so in-depth that they were able to conduct extensive rehearsals upon rapidly assembling.[12] The use of warning and fragmentary orders and rehearsal of concept (ROC) drills ensured a shared understanding of the plan for Fallujah’s north to south clearance.[13] Rehearsals with attached mechanised Army commanders developed a shared understanding of how to maximise combined arms capabilities in the urban environment in order to support 1MEF’s plan.[14] Importantly, rehearsals were conducted at all levels, but attendance was not always achieved by flanking calls signs at the lower echelons.[15]

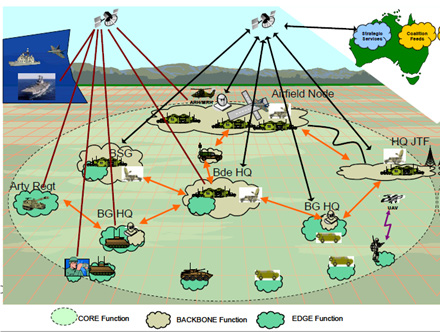

1 MEF’s ability to clearly convey the commander’s intent for the urban clearance ensured the mechanised forces leading the assault into the city avoided dislocation because control measures for the sequence of manoeuvre were considered.[16] Commanders successfully coordinated offensive support largely due to their impressive shared understanding of the fight. Synchronisation of offensive support between elements was effective against hard points, ultimately enabling the initial breach into and continuous clearance through Fallujah.[17] Crucially, the commander’s intent, shared understanding and synchronisation were enhanced through the established digital communications on assembly, allowing distinct groupings to coordinate in unison to support the command and control function.

Natonski and his subordinates coordinated post-H through Blue Force Tracker, tactical chat, and radio which without their rapidly established communications theatre gateway on marrying up would have fallen short of 1 MEF’s requirements. Most importantly, this was enhanced through battlefield circulation between divisional, regimental, and battalion headquarters.[18]

Through his presence, Natonski ensured senior commanders were up to date with changes to the plan despite technological issues such as communications security (COMSEC) change-over during the operation and the issuing of regimental and divisional fragmentary orders via inaccessible communication systems. The requirements of a robust communications plan, with associated standard operating procedures, realised through battle preparation and rehearsals and into execution was reticently acknowledged by commanders post the mission.[19] Regimental Combat Team (RCT) Commanders held face-to-face discussions with their subordinates as to changes in the manoeuvre plan and opportunities to support flanking elements.[20] This included employment of mechanised assets to assist dismounted elements during the clearance, and included evacuation of personnel as well. Additionally, close air support allocated between flanking elements was effective in supporting the parallel clearances as a result of senior commanders coordinating efforts.[21]

Rehearsals, mission command and battlefield circulation are essential elements of communicating a plan regardless of the means and methods used. Rehearsals ensure everyone knows what to do at points of friction. Rehearsing reveals the issues commanders may not have considered in their planning and it allows subordinates to suggest solutions to rectify them. Key to this is including amendments to control measures, how capabilities are employed and ensuring a communications plan and supporting processes are robust. Mission command ensures execution post-H is effective. Commanders must have a clear understanding of the plan and what degree of freedom of action they possess in support of the higher commander’s intent. Battlefield circulation allows appreciation of the terrain and for the sharing of intelligence. These methods, especially when employed in volatile and ambiguous environments, ensure the intended actions of a commander’s plan become reality.

Operations Compass and Al-Fajr demonstrated how communicating the plan effectively enabled reconnaissance pull against an enemy because subordinate elements could determine enemy strengths and weaknesses and how the plan intends to target those weaknesses.

O’Connor and Natonski used rehearsals effectively to communicate their plans. During Operation Compass, O’Connor’s rehearsals for Nibeiwa were veiled as 'tactical exercises without troops' knowing they were going to assault Nibeiwa. And yet, the rehearsals were so effective that troops were able to seamlessly apply combined arms integration onto real terrain.[22] Rehearsals ensured that, when conducting combined arms actions, elements acted in concert to identify, create, and exploit gaps rapidly. The exploitation of gaps at Nibeiwa, Bardia, and Tobruk compounded the success of Allied forces, reducing losses and preserving combat power. Over 60 years later, 1 MEF ensured numerous elements came together and gained an understanding of a complex task to clear an entire city in limited time. Rehearsals allowed the Marine and Army commanders to ensure mechanised employment was effective, resulting in the rapid clearance of the city. Integration of combined arms elements were more effective when they participated in each other’s rehearsals or O-Groups. Notably, tempo of the clearance was impeded when flanking call signs did not participate in rehearsals intended to provide detailed coordination.[23] Rehearsals led both forces to exploit opportunities presented to them and subsequently employed reconnaissance pull to avoid defensive strengths, creating sustained success without suffering significant losses.

Both commanders applied the pre-requisites of mission command in order to more effectively communicate their plans. Because they understood O’Connor’s intent, air and ground reconnaissance forces identified weaknesses in the enemy disposition, including lack of depth, mutual-support, and observation. The shared understanding gained from this reconnaissance subsequently allowed commanders to exploit these positions. O’Connor so effectively conveyed his intent to subordinate commanders that, without coordination post-H, they adapted the plan to stop the Italians from withdrawing to Tripoli. This demonstrated a mutual trust that O’Connor had placed in his subordinates and a reliability shown in them to accomplish his intent. Common tactical doctrine shared between the WDF ensured combined arms in the assaults exploited opportunities and blocking forces denied enemy manoeuvre for withdrawal. In Fallujah, the shared understanding of control measures described in orders enabled lead mechanised elements to avoid dislocation from dismounts by reliably adjusting their manoeuvre. Likewise, the mutual trust that existed between the Marine Regimental HQs and Army mechanised units allowed them to target enemy positions in depth and reduce risk to personnel by supporting dismounted manoeuvre and facilitating casualty evacuation. Mission command through shared doctrine, understanding, trust, and reliability results in reconnaissance pull when the plan is effectively communicated.

In Operation Compass and Operation Al Fajr, the commanders practised battlefield circulation to great effect. Battlefield circulation resulted in a plan that was well understood throughout all levels of command. O’Connor consistently travelled to subordinate positions to ensure they understood the gaps to be exploited in the enemy plans. In one particular example, captured maps recovered from enemy positions were analysed and subsequently presented by O’Connor himself in his orders groups. This led to the probing of enemy positions to identify where the combined arms assault could penetrate.[24] The result was that O’Connor’s subordinates were often positioned to exploit opportunities when limited communications were available.[25] Battlefield circulation for 1MEF in Fallujah meant priority of support and weight of effort could be re-allocated when units were in need. Command and control limitations, due to the lack of investment in the communications plan prior to H-Hour, necessitated face-to-face discussions, including on rooftops during the battle, as the plan and enemy disposition changed. Natonski’s personal presence, as well as RCT commanders, amongst manoeuvring units ensured opportunities were realised and friction was overcome, such as the dynamic reallocation of close air support and tactical unmanned aerial surveillance to units. Mechanised forces were redirected post-H to support other dismounted elements and assist in casualty evacuation when suggested by tactical commanders. Commanders discussing the battle in person allowed for better battlefield visualisation and inspiration, such as the clever employment of bulldozers and tanks to demolish challenging strong points and ensure momentum was maintained. This ensured opportunities were exploited with an informed chain of command achieving a high tempo throughout the overall clearance. Decisions made before, during, and after an offensive action focused on targeting the enemy’s weakness and avoiding the identified strengths, taking advantage of the fleeting opportunities that presented themselves in line with employing reconnaissance pull.

Reconnaissance pull – targeting enemy weakness, avoiding strength, and exploiting available gaps – ensures commanders consider how best to employ their force with a comprehensive and common understanding of the enemy.[26] It emphasises a knowledge of opportunities and when to take them. Aligned to Accelerated Warfare and in the context of being ready now, Army’s teams should apply the principles of reconnaissance pull to understand the rapidly changing character of warfare which will present as the modern battlefield. In an environment defined by hybrid threats and decisive action, leveraging the ability to effectively communicate the plan ensures Army’s teams can respond appropriately in any tactical situation. Commanders must consider the opportunities our current digital communicative technologies offer in terms of communicating a plan in a broad and timely manner. The testing of those technologies during battle preparation must also be given due consideration. In addition, commanders should not be constrained to a single source of distribution, and should continue to pursue parallel forms of communication including battlefield circulation and hand written messages. In a contested multi-domain environment, the means to communicating the plan are as essential in planning as they are in the execution phase. Operation Compass and Operation Al Fajr define communicating the plan in the ready now context. Both case studies demonstrate that orders and rehearsals, post-H decision making with the commander’s intent in mind, and the ability to conduct face-to-face coordination inculcates a mindset of creating and exploiting opportunities.

This article was originally published in the CTC Live 2020 Fight to Win paper: