Leadership is an intangible and vital element of warfighting which directly influences the outcome of a battle. Described as an art, leadership is the ability to influence troops at a personal level rather than relying solely on rank or position in order to gain advantage over the enemy. Effective leadership generates decision superiority by enabling initiative and generating tempo. Conversely, poor leadership can reduce an otherwise effective force to failure. Lieutenant Colonel Herbert Jones VC, OBE, in the Battle of Goose Green, and Major Harry Smith SG, MC, in the Battle of Long Tan demonstrate how trust, understanding, and risk are fundamental elements of effective leadership.

The Battle of Goose Green was fought from 28-29 May 1982, between the United Kingdom and Argentina as part of the Falklands War. The Argentinians, led by Lieutenant Colonel Italio Piaggi, established defensive positions around the settlements of Goose Green and Darwin with a force consisting of three infantry companies, eight batteries of anti-aircraft guns, and a battery of 105mm pack howitzers.[1] Lieutenant Colonel Jones commanded the British 2nd Battalion, Parachute Regiment, which consisted of three infantry companies, a patrol company, a support company, a battery of 105mm howitzers, and an anti-tank platoon.[2] Jones’ mission was to conduct a raid to capture the settlements of Goose Green and Darwin before withdrawing to become the reserve for subsequent operations.

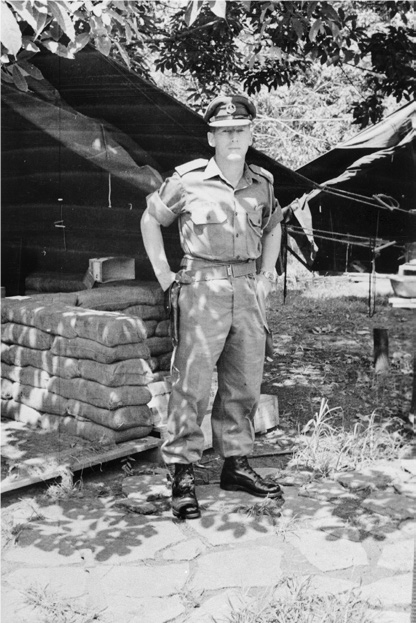

PA Images no. 1456150 / LTCOL Herbert Jones

Jones had an uneasy relationship with his subordinate commanders, resulting in a low level of trust throughout the command. This was demonstrated during the battle when one of the company commanders reported the situation in front of his company to Jones via radio. Jones required the company to remain in position so that he could advance to the company’s location to assess the situation for himself. The distance travelled across uncleared ground and the time required for Jones to do so were considerable, which added unnecessary risk to himself and his unit. This additional time enabled the Argentinians to retain the initiative.

There was a lack of a common understanding between Jones and his subordinate commanders as to the Argentine forces located in the Goose Green area prior to and during the battle. This was caused when Jones cut short the intelligence briefing before his orders due to time constraints. This error was compounded by the fact that the enemy situation had changed significantly since the last intelligence update, as reported by a Special Air Service observation post onto the settlements. Analysis of the information gained by the patrol would have identified a weakness in the Argentine defences.[4] Without shared understanding and effective mission command between Jones and his subordinate commanders, there were limiting factors which would impinge on the eventual success of the mission.

Jones placed himself and his unit at risk when, failing to recognise his force was insufficient to capture Goose Green and Darwin, he attacked the outmatched Argentine force regardless. It was only because the Argentines surrendered that the British did not sustain even greater casualties as they achieved the capture of the settlements. Jones was physically too far to the rear when the battle commenced, degrading his ability to effectively lead the forward elements. To rectify both command and control, Jones advanced to the lead company’s position, yet both Jones and his Adjutant were decisively engaged by an Argentine machine gun position at the front. Both men were killed while attempting to clear the position, and Jones was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross for this action.[5]

The Battle of Long Tan was fought on 18 August 1966, in Phuoc Tuy Province, South Vietnam between Delta Company, 6th Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment (6 RAR) and the Viet Cong’s 275th Regiment supported by the 445th Battalion. Delta Company, under the command of Major Harry Smith, had been tasked to patrol east of Nui Dat to clear possible enemy positions which had been mortaring the base the morning prior.[6] As Delta Company commenced their patrol from Nui Dat and cleared the rubber plantation in vicinity of the village of Long Tan, the company was engaged from the east by elements of the 275th Viet Cong Regiment and later the 445th Battalion, totalling approximately 2,000 soldiers. Delta Company was supported heavily by 105mm and 155mm artillery and reinforced by 3 Troop, 1st Armoured Personnel Carrier Squadron and Alpha Company, 6 RAR, causing the Viet Cong to eventually withdraw.[7]

There was a significant level of trust between Smith and his subordinate commanders, as demonstrated during the battle when his platoon commanders reported an enemy force which was far greater than that which had been assessed. Smith believed the assessment of the lead platoon commander and called for danger close offensive support – an unlikely and dangerous thing for a commander to do unless he trusted his subordinates implicitly. In addition, the common understanding between Smith and his subordinates prior to and during the battle enabled effective passage of information from the forward line, back to Smith and upwards to Task Force HQ. Communicating accurate locations of friendly and enemy forces, in addition to battlefield commentary, enabled a common operating picture from which individuals could appropriately respond. This passage of information and accuracy of reporting enabled danger close fire missions without causing friendly casualties in addition to the conduct of aerial ammunition resupply of a complex battlespace.

Smith took prudent risk during the battle by conducting an assessment of the enemy strength and identifying that it was a superior sized forced. Once identified, the company adopted a defensive posture and Smith positioned himself to have sufficient situational awareness and effective command and control of his forces. Further, Smith enabled Captain Morrie Stanley, the forward observer attached to Delta Company, to remain static, enabling him to call for accurate fire support for the lead platoons. Again, Smith took the considerable but prudent risk in ordering a danger close fire mission to prevent the enemy from overrunning Delta Company’s position.

Trust, understanding, reliability, and risk combine to form the basis for effective leadership in the Battle of Long Tan, where said elements are largely absent from the Battle of Goose Green. Leadership is primarily about the influence of followers engaged on a personal level.[8] The ability to motivate and inspire followers relies heavily on trust and mutual understanding. Followers need to believe that the leader will only take considered risk on their behalf for the leadership to be truly effective. Smith demonstrated the importance of trust in command, built during additional training he directed Delta Company to conduct above the rest of the battalion. He had faith in the information that he received from the front, resulting in him not having to move forward to confirm the situation on the ground. Smith’s leadership contributed to his superior decision cycle, as it enabled rapid offensive support to suppress the enemy. If Smith were required to move forward to confirm the Platoon Commander’s assessment, it could have resulted in a delay in offensive support and Delta Company’s position being overrun. Further, it is likely Smith would have been decisively engaged and caused further delays.

Jones’ level of trust towards his subordinates was limited, which meant he felt he had to personally confirm the information he received from his subordinates, taking additional time to make decisions and further undermining his leadership and degrading his decision superiority. His movement to the forward line to assess the situation himself enabled the Argentinians to have freedom of action during this time of indecision. If Jones had trusted his subordinate commanders, he could have issued orders without moving forward, thus increasing the tempo of his unit. The lack of common understanding between Jones and his subordinates stemmed from Jones failing to pass critical information, leaving his subordinates unclear of the disposition. If Jones’ company commanders had an understanding of the Argentine positions, it is likely that additional direction from Jones would not have been required. Compare this with the shared understanding during the Battle of Long Tan where Smith provided critical information such as friendly and enemy dispositions, which enabled the effective marry-up of more than two units in contact without generating friendly casualties. This is a direct result of members of Delta Company and relieving elements having a common understanding of doctrine and standard operating procedures.

Seeking to mitigate risk is a critical element of leadership that can lead to decision superiority. Jones engaged a dug-in defensive position without a greater force ratio. Had Jones identified that he did not have the force ratio required to capture Goose Green, he should have mitigated the risk by requesting additional assets or opting to only conduct a raid on the garrison within the Goose Green area – a task he could have likely achieved. Jones was decisively engaged and died as a result, thus providing no further leadership for the duration of the battle. During the Battle of Long Tan, Smith identified that his force was numerically smaller and didn’t have the required combat power to assault the enemy positions, so he decided to adopt a defensive posture whilst requesting support from higher. It was only when Smith received reinforcement in the form of Armoured Personnel Carriers that he initiated an assault upon the enemy positions. Had Smith attempted an assault with only his company, it is likely that it would have resulted in its destruction given the vastly numerically superior force and the difficulties in adjusting danger close offensive whilst in the assault.

Smith’s superior leadership directly contributed to decision superiority by enabling Delta Company to make timely and tactically sound decisions, which ultimately led to the successful defeat of a significantly superior sized force in an encounter battle. Smith was able to observe the action of the Viet Cong, orient his company and supporting assets, decide on a course of action, and communicate that all effectively to his force. This enabled his force to act faster than the Viet Cong. In the Battle of Goose Green, Jones’ autocratic leadership style did not generate decision superiority. Following Jones’ death, Major Chris Keeble, the Executive Officer, assumed command from his position in the Battalion Command Post located to the rear. With better situational awareness and understanding, not least forced by circumstance, Keeble took charge of subordinate call signs, issued rapid orders and achieved the decision superiority that undermined Argentine defences and led to the conscripts surrendering. Although the two battles resulted in the same number of killed in action, the scale significantly differed. The Battle of Long Tan was a company versus a regiment, while the Battle of Goose Green was a battalion versus a battalion.

As Smith demonstrated through his actions during the battle of Long Tan, a commander’s leadership ability directly impacts a force’s ability to generate decision superiority which provides a force with a competitive advantage over the adversary. In order to retain the ability to defeat a numerically or materially superior adversary, Army needs to continue to develop leadership at all levels to build trust in teams, engender shared understanding, promote reliability, and enable subordinates to demonstrate disciplined initiative.

Accelerated Warfare identifies that current and future battlespaces will be substantially different from the past as they will be contested across not only the traditional domains of air, land and sea, but the newly contested domains of cyber and space. In order to meet the aim of defending Australia and its interests, the ADF will require effective leadership at all levels across the spectrum of warfare. The concepts of ready now and future ready identifies that Army needs to be prepared for increased cooperation, between not only ADF, but other government departments, non-governmental organisations and other defence forces. The concept also states that there will be additional competition from other state and non-state actors against Australia and its interests. To match the uncertain, changing and diverse nature of future conflict, a commander’s ability to employ the key elements of trust, understanding and risk in their leadership style will be crucial in maintaining a competitive advantage.

This article was originally published in the CTC Live 2020 Fight to Win paper.