When the former Coalition Government announced in March this year it’d be spending $38 billion to increase Defence’s workforce to over 101,000 by 2040, the intent was that most of this growth would go to the permanent ADF. Notably, former Defence Minister Peter Dutton aimed to “increase [the permanent ADF] by around 30% by 2040 … to almost 80,000 personnel”.

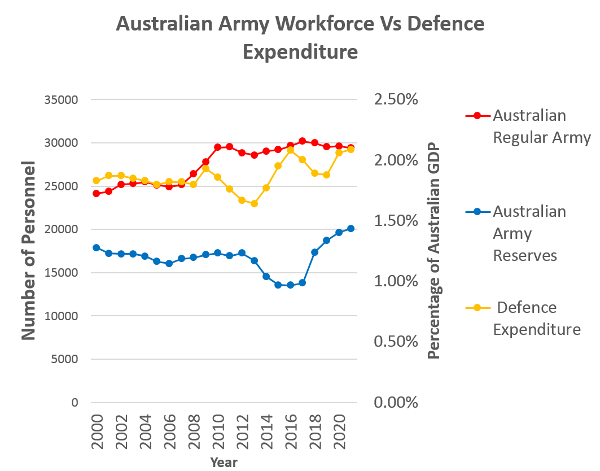

However, in reviewing historical data of the Australian Regular Army (ARA) workforce in comparison to that of the Army Reserve, no correlation exists between the size of the ARA workforce and Defence expenditure.[1] There is; however, a significant correlation between Defence expenditure and the size of the reserve workforce.

I propose this may be due to a difference in motivation between the two service categories, which can be linked to recruitment literature. If correct, Government policies to merely increase Defence expenditure as a means of boosting retention and recruitment may not have the desired effect of increasing the size of the ADF’s permanent forces.

Method

In conducting this research, the Defence Annual Reports from the years 2000-2021 were reviewed to gather the size of the Australian Army’s workforce for each year. This data was categorised by state of work location and service category (permanent or reserve).

Data on Defence expenditure as a percentage of Australian GDP was then drawn from World Bank data and compared with the above dataset.

Results

At first glance the data seems unremarkable. There appears to be consistent growth in the size of the ARA since 2000; and a dramatic decrease in the Reserve workforce from 2014-17 seems to disproportionately affect the eastern states of QLD, NSW and VIC, where the largest numbers of reservists were located. States containing a smaller workforce were relatively unimpacted during this time.

When Defence expenditure is inserted into this dataset however, an obvious trend emerges. While the ARA workforce is consistent throughout the 20-year period, the size of the Reserve workforce fluctuates a few years behind similar patterns in the Defence expenditure data.

To see whether a correlation exists, the R-squared value of Defence expenditure and its relationship to reservist workforce strength was calculated. As it takes time for policy decisions to be implemented, I compared the relationship between the data given for a range of years’ ‘delay’. When Defence expenditure is shifted forward by 3 years, R-squared peaks at a value of 0.65 (statistically significant).

Discussion

The above research indicates that a policy decision to increase or decrease Defence expenditure as a proportion of GDP impacts the size of the reserve workforce – but does so in a ‘delayed effect’ of 3 years. This makes sense as any policy decision would take a few years for its effects to be felt by the workforce ‘on the ground’. However, there exists no such relationship between Defence expenditure and the size of the ARA workforce – which has experienced consistent growth over the last 20 years.

Why does the ARA not respond to a change in Defence funding, but reservists do so significantly? Military officers-turned-academics James Griffith, Patrick Bury and Sejin Park suggest this may be due to the significant differences in motivation for those joining the ARA versus those joining the Army Reserve.

Recruitment theories categorise a member’s motivation to join the permanent armed forces (like the ARA) as “transformational”, based upon “ego” and “social” factors. Such reasons to join may be to serve a higher purpose, to be a part of a team, to prove oneself, or to gain pride that may come from wearing the uniform. These factors seem reasonable because an organisation such as the ARA requires long-term commitment and loyalty.

Reservists, to the contrary, have been categorised by recruitment academics as being mostly attracted to “informational” or “rational” reasoning when joining. These include reasons highlighting the tangible benefits of joining the Army Reserve such as a tax-free income, health and mortgage assistance, and the ability to continue civilian employment during enlistment.

Conclusion

Further research needs to be conducted in determining why the strength of the Reserve workforce fluctuates so closely with Defence expenditure. Is it possible that fewer opportunities, less training days and fewer resources – over a sustained period of several years – contribute to a reservist deciding to leave the Army?

What is clear is that the ARA workforce historically does not respond to any changes in Defence expenditure. Any policy to significantly grow the permanent ADF will therefore need to consider other approaches that take into account the ‘transformational’ motivation to serve.

Scope for further research

There exist several avenues for further research in support of this research question:

- What is the break-down of recruitment vs attrition within the personnel strength data listed? Are increases in personnel strength a result of greater recruitment or greater retention?

- Previous work has been done to ‘profile’ Reservists based upon their motivations to join and remain in the Army. What impact do changes in Defence expenditure have upon each of these groups?

- Could this same profiling be done on ARA units to test the theory of ‘transformational’ motivation?

- Such data can be easily broken down by state of work location. Do significant trends appear in this dataset?

- Does the same trend appear amongst the other services?

How about the link between transfer to Ser7 from Ser5? Is this affected by funding? Do reservists see opportunities and transfer across? Or do they see the opportunities going elsewhere in Army and 'take their bat and ball' and go?

Is the lag actually correllated to the funding? Or is the drop in numbers actually related to the increased funding which means increased training and increased demand on Ser5 which means some go " this is no longer a part time commitment, I need to focus on the main income providing job' and leave.

Either way, good luck. We need to keep working on how we enlist, motivate, retain and seperate ( perhaps only temporarily) our soldiers, no matter what Sercat.