Against the backdrop of great power competition, multi-domain operations, and an increasingly complex threat environment; it is necessary to analyse and understand the need for cognitive diversity in our military to ensure the ADF is best equipped for the geo-political challenges to come.

The ADF is currently undergoing necessary changes in how it engages in and teaches warfighting, as well as how it adjusts to the everchanging character of war. In order for these changes to be implemented successfully, it is vital that Defence realises the importance of diversity in the way our people think. This article will seek to define cognitive diversity and subsequently analyse and discuss different types of thinking. It will then assess how these different types of thinking contribute to success in military teams. Furthermore, it will put forth three recommendations that the ADF can incorporate to attract diversity of thought within its ranks.

What is cognitive diversity?

Cognitive diversity is the ‘bringing (of) divergent perspectives to the problem in order to redefine or broaden the problem or generate a greater number of possible solutions.' Humans have inherently different cognitive traits, which stem from factors such as upbringing, education, values, and different experiences that make up our personality and thinking styles.

Those in the military context are extensively trained to deal with complex and uncertain operating environments and are forced to make quick, logical decisions under extremely stressful conditions. These individuals are highly educated and professionally trained in the science and art of war and are also provided the opportunity to focus their training to form a specialist skillset. The universal way of teaching in the military begs the question: is there too much of an emphasis on simple linear thinking?

As Patrick Oddoux argues, ‘applying a linear thinking approach to diagnose complex systems, such as trade, economy, taxes, financial markets, energy, immigration, etc ... will lead to misguided policies.’ Furthermore, those who negate the complex nature of the world are doomed to ‘watch the emergence of consequences they could not foresee through linear analysis.'

The same is true for individuals, leaders, and commanders in the military due to the shifts in the global status quo and the problems that arise within. It is essential to be able to employ people with a broad spectrum of thinking styles to best solve the problem.

If the threat environment in which we operate has increased in complexity, why would we encourage Army’s people to think alike, using the very same processes as the person next to them?

Vertical (linear) vs Lateral Thinking

Vertical thinking or linear thinking is 'thinking that proceeds in a stepwise fashion applying specific rules in order to reach a definite goal… it is linear and left-brained, selecting only what is relevant.' Vertical thinking has been the dominant method of thinking in the military and is the foundation of thought processes that students of military art and science are taught.

An example of this in the Australian context is the Military Appreciation Process (MAP) which is an effective, step-by-step, logical process to solve military problems. The MAP is a widely accepted tool for commanders and staff to come to a logical and informed decision and has proven effective on many operations.

In 1995, the US Army Research Group tested the performance of different groups of planners on a divisional level. The conclusions made were that the groups that followed a structural process, similar to that of the MAP achieved better results ‘due to more rigorous consideration of the relevant factors'. Critical components of the MAP and military problem solving in general are the use of timelines for developing courses of action, employing end-states, lines of effort, and other linear constructs. However, perceiving the world in such a step-by-step manner and as a series of isolated events renders linear thinking habitual to us as military thinkers and planners.

As a result, what ensues is an over-simplification of reality that tends ‘to miss the complexity of interactions that have taken place in dynamic and chaotic conflict environments.'

The process itself does not create ideas and relies on the role of the human using it, thus 'the MAP is only as good as the ideas fed into it.'

Ben Zweibelson in his article in the Canadian Military Journal entitled ‘Linear and Non-Linear Thinking: Beyond Reverse-Engineering’, explains that linear thinking and analytical reasoning work best when the stringing together of ideas occurs in a neat sequential order i.e. A plus B, then C. However, as he argues, the A then B approach becomes burdened outside sterile laboratories due to the natural messiness of human complexity. Moreover, unlike the hard sciences, the dynamic and complex nature of human societies (to include warfare) prevents us from relying exclusively upon analytical reasoning to understand reality (Ibid, 2016).

Lateral thinking, first coined by Edward De Bono in 1967, is a form of creative thinking that incorporates imagination as well as abstract and logical reasoning. Lateral thinking (or horizonal thinking) is not bound by logic or goals. It’s also non-linear, adding imagination to reasoning abilities, thus creating new and creative ideas, or in simpler terms, the ability to develop original answers to difficult questions. Zweibelson terms this style of thinking and sensemaking as ‘holistic non-linear worldview’, which can still function within the analytical world and beyond.

The advantage of lateral thinking in the military context is its ability to explain the causality of the abstract, as well as the existential, post-modernist and constructivist worldviews, which the analytical perspective is often unable to succeed in doing. This is most evident in the complex operating environments where western militaries have the tendency to rely on linear understandings of the battlefield.

The war in Afghanistan has been perhaps the best example of this in the past 20 years. From the beginning of the conflict, the West failed to understand the operating environment and subsequently developed policies that were inadequate for dealing with the political, economic, and particularly ethnic and cultural complexities of the country. By 2012, the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) had learnt its lesson and had hand-picked military planners to best make sense of the environment. By forming this team with dissimilar perspectives, each planner contributed to the holistic perspective of the functioning of the NATO Training Mission.

As a result of diversifying the cognitive abilities within the team, it permitted them 'to appreciate complex environments without shackling them to the inhibiting elements that maintain organizational uniformity, repetitiveness, and hierarchical control [-freedom from which] nurtures critical and creative thinking.'

The same can be said for comprehending and predicting the intent of adversarial actors and their use of asymmetrical warfare and grey zone tactics to achieve a political, economic, and military goals.

The roots of such a lack of understanding of differences in the operating environment can be traced all the way back to initial training, as argued by Jack Cross. An example of this occurs during officer training at the Royal Military College – Duntroon (RMC-D), where the encouragement of creative thought for cadets undergoing the initial training phase is hindered by the prescriptive training approach. Trainees are 'shaped into a pattern of behaviour which minimises lateral thinking … in an attempt to avoid scrutiny from instructors.'

This discouragement of lateral thinking, he argues, is also prevalent across other army officer training institutions in the US and UK. It is imperative that lateral and creative thinking is not just encouraged in training institutions but also implemented into the curriculum across our partners and allies. It is acknowledged however that these institutions are also undergoing large change in line with that of the ADF.

The Toolbox of Lateral Thinking:

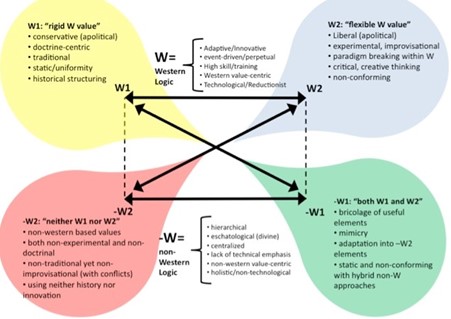

A tool utilised in the arsenal of Lateral Thinking is the ‘Semiotic Square’ that offers a useful non-linear construct by which to build strategies and explore the interplay between conflicting world views (Shultz and Hatch, 1996). The Semiotic Square functions by ‘embracing paradox, conflicts and similarities’ which allows the user to recognise institutionalisms and the different languages of distinct world views.

As shown below, the Semiotic Square provides a non-linear equation for problem solving. In summary, while vertical thinking develops an existing pattern, lateral thinking seeks to restructure it. For an institution such as the ADF, one can see how ensuring both thinking methods are employed would be an asset to its thinking arsenal.

Figure 1. The ‘Semiotic Square’

Diversity in Teams:

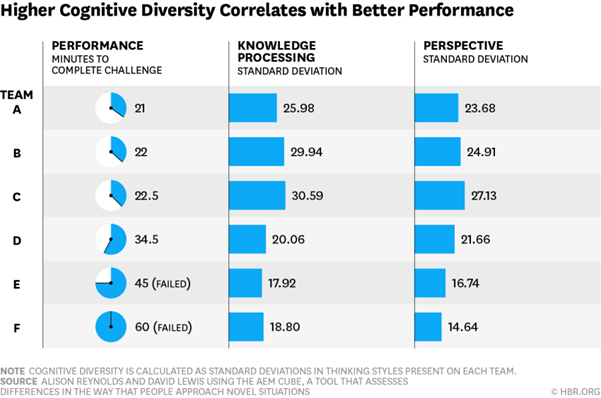

Exploring cognitive diversity and how it impacts the way we think about and engage with new, uncertain, and complex situations is critical in the military team-based environment. Alison Reynolds and Ryan Lewis study this topic in great depth within their article published in the Harvard Business Review. The two authors conducted a study using the AEM Cube, a tool used to assess individual and group cognitive approach, to assess the performance of both cognitively and non-cognitively diverse teams when given a complex problem set.

The tool measures ‘knowledge processing’; the extent to which individuals prefer to ‘consolidate and deploy existing knowledge, or prefer to generate new knowledge, when facing new situations and ‘perspective’; the extent to which individuals prefer to ‘deploy their own expertise or prefer to orchestrate the ideas and expertise of others, when facing new situations’. Six teams were created from the result of the AEM Cube, three of which were more cognitively diverse than the other three. From the analysis of six teams, they discovered a significantly high correlation between high cognitive diversity and high performance.

Figure 2. High cognitive diversity and high performance

In this chart, the higher the standard deviation the more cognitively diverse the team. Teams A, B, and C – being the most cognitively diverse – solved the problems quicker and more successfully.

An example of this in the military context during the Iraq War was shown by retired US Army General Stanley McChrystal, former commander of Joint Special Operations Command, who identified a lack of diversity in the team under his command and sought to implement policies to break down barriers within the task force. Despite a diverse group of Navy SEALs, army special forces, and other elite units under his command, the groups had difficulty integrating their efforts to collaborate effectively, due to group identities.

GEN McChrystal responded by incentivising highly skilled operators to be embedded in key positions within other units and emphasising the importance of liaison officer roles. Over time internal barriers were broken down, permitting the entire task force to blend group identity as well as diversifying the thought processes and ultimately driving positive mission outcomes.

It is evident that cognitive diversity provides several advantages to military teams for task completion as well as broader perspectives for problem solving.

Conclusion. Messy problems demand innovation. Three ways to ensure the diversity of thought.

The necessity for cognitive diversity in modern militaries is paramount to successfully address, understand, and solve presented geo-political and strategic problems. The times in which conflict was one-dimensional, the threat was easily identifiable, and linear thinking was all that was required are long behind us. As such, here are three recommendations to ensure that the ADF is best equipped for the challenges ahead:

- Encourage cognitive diversity in training institutions. We train the way we fight, the ADF must also train with the diversity of thought.

- Leaders at all levels must identify those in their teams with different thinking styles and ensure that they are brought into the problem-solving process.

- Promote all ranks to employ different methods of thinking styles as well as different problem-solving frameworks to tackle dilemmas and crises in unusual and creative ways.

The problems and threats that we face as a military today are multi-dimensional, complex, and grey in nature. As the modern military trains for diverse mission requirements, it must encourage diversity of thought as the strength of our military comes from its people and the various experiences that they bring to the fight.