Introduction

The Australian Army has a data problem. The problem isn’t small or manageable and is getting exponentially bigger every year. The problem stems from the fact that data production is expanding at a rapid rate, both on the battlefield and in a global context. While many are heralding Artificial Intelligence (AI) as the saving grace that can help us manage the overwhelming data/information problem, it’s not that simple.

A familiar axiom in military parlance is that amateurs talk strategy; professionals talk logistics. The explanation is that logistics form the immutable foundation that both strategy and tactics require. This theme carries through to AI, with the foundation being the data and information that feed into AI systems.

This concept is reflected in comments by Craig Martell, the US’s Department of Defense’s first Chief Digital and AI Officer – stating that more attention and energy needs to be paid to data, which serves as the basis of the AI’s hierarchy of needs. Martell states that the “foundation is data, quality data, accessible, clean, regularly updated and with a notion of ownership”. Martell has correctly asserted that whilst the broad flexibility of AI makes it a powerful combat multiplier, AI is only as good as the data it receives and is trained on. Military organisations must have a good idea of how information flows on the battlefield before they can apply a comprehensive AI solution to manage it.

How Important is Information on the Battlefield?

The importance of the relationship between information and warfare has been continuously emphasised and recorded throughout history. Sun Tzu famously wrote that all of warfare is based on deception. Whilst this statement is not wrong, and undoubtedly, the primary objective of any combatant during warfare is to deceive the adversary (to make winning easier), the subtlety of Sun Tzu’s profound statement runs deeper than deception.

Deception could be viewed as manipulating information that is either displayed or portrayed to the enemy to coerce them into an action while the friendly force protects its own sources of information. This information input (and output) is a critical component of warfare, and all decisions that flow from this information input are assessed in context with temporal and uncertainty pressures.

A more accurate statement may be that all warfare is fundamentally based on information, both in the control and use of it.

Given that information dominates all aspects of warfare, the problem set extends to how a military can best filter, control, categorise, and distribute the types of information on the battlefield. Military decision-makers are often faced with complex decisions in non-routine situations – often for which no rules-based solutions exist. These decisions are framed in an environment of uncertainty, and to be effective, decisions need to be made on up-to-date, relevant, and timely information.

Data vs Information

While information and data are interrelated, they are separate and distinct components. The term information can be defined in various ways, but the broadly accepted definition is that information is processed, organised, and structured data presented in a meaningful context.

Information is predominantly fed by data – a collection of raw, unorganised facts and details, like figures, observations, text, symbols, and descriptions of things.

Without context, the process appears straightforward – military commanders take raw, unorganised facts and details, filter, process, and structure them to gain information that can be utilised to decide, translating data into an action or order that creates an effect. Whilst the solution is simple, ensuring commanders have reliable, relevant information at the right time and place has consumed military thinking power for decades. With no clear answer on the horizon, the flexible nature of AI offers a potential solution to the problem.

The growing problem

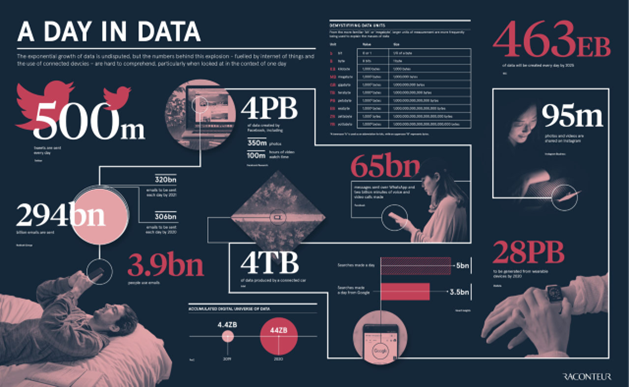

The concerning thing is that this data problem is increasing at a near-exponential rate. In 1986, the estimated global data generated for the year was 2.6 exabytes. This number has seen an exponential increase over the past four decades, with a recent study by Raconteur estimating that by 2025, the global population will generate 463 exabytes of data per day.

This growth of data is also witnessed on the battlefield. Consider an eight personnel section, each member equipped with some sort of multi-spectral sensor or real-time video recording system. Additionally, the section has several autonomous vehicles – both air and ground supporting them. This section has the capacity to generate 75 Megabytes/second of data. That’s 4.5 Gigabytes per minute, 270 Gigabytes per hour, or 6.5 Terabytes per day. That is a phenomenal amount of raw data, which must be managed or processed in some method.

This exponential growth is being witnessed in conflicts today, highlighted by the war in Ukraine with a blending of military & civilian data sources. High-resolution imagery from Maxar is being used to track tank convoys, skirmishes posted on TikTok alert data gatherers about battles, and Ukrainian intelligence receives tens of thousands of daily reports on Russian movements.

Big Data

So how do we address the problem? The concepts of ‘Big Data’ have been studied for a number of years, and big data is typically broken down into different components and address data that contains greater variety, arriving in increasing volumes, and with more velocity (the three V’s). These three V’s were first termed in a Gartner blog by Doug Laney, and they have been supplemented with some emerging V’s over the past decade – Value and Veracity. Each aspect is relevant to the modern military information problem.

Volume is a characteristic that indicates the magnitude of data, often measured in terabytes or petabytes of data. The processing capacity of a system tends to throttle the volume of data that a system can receive. In a military context, this often presents challenges due to the limited and contested nature of data transfer networks. This capacity limitation may require the application of edge computing – where data is processed either at the source or near to the source. Edge-computing reduces the requirement to transmit large amounts of raw data.

Velocity typically refers to the rate at which data is in motion and is throttled by the rate of generation or the required speed of analysis and decision support. In a military context, the core limitation is the ability to process the volume of data generated at the velocity required to be effective, with the problem referred to as the “input-output problem”. This limitation can be weaponised, as observed in 2014 when Russia overwhelmed a Ukrainian system by inundating it with more data than it could process.

Variety refers to the types of data that are available, with traditional datasets that were structured or organised into a database. Unstructured and semi-trusted data types such as text, audio, and video require additional pre-processing to derive meaning and support metadata. Due to the broad nature of the operating environment, militaries are exposed to a wide variety of both structured and unstructured data.

Value represents the expected result of processing and analysing the data, which is often low before analysis of the data. Most data possess some form of inherent value, but it is of no use unless the value is drawn out. In an adversarial environment like warfare, the hidden value of aggregating data could provide a significant combat advantage once appropriate analysis has occurred.

Veracity refers to the truthfulness and reliability of the data – given that data can be based on datasets of varying degrees of precision, authenticity, and trustworthiness. In the context of warfare and the potential application of violence against humans this is of utmost importance.

“Good” information vs “Bad” information

The other challenge that is posed with data and information management is that there is no specific measure or guarantee that the data or information will be in any way accurate or correct. The situation is so bad that three individual terms have had to be coined to describe the different types of ‘bad information’. Generally, whilst AI systems can be trained to manage bad information, the more reliable solution is aggregating information from a variety of sources.

Firstly, we have misinformation, typically defined as false, inaccurate, or misleading information deliberately or unintentionally shared or promoted as correct. Whilst sharing misinformation may be deliberate to support viewpoints, the sharer assumes that the information is accurate and correct.

Secondly, disinformation introduces a deliberate component – the information is known to be untrue or misleading, but the author consciously decides to promote fake news or propaganda. Disinformation is meant to influence how people think about divisive subjects such as politics or social concerns.

The final element of bad data is malinformation. Malinformation is accurate and factual information but is conveyed in a manner that aims to inflict harm or threat of harm on a person, organisation, or country.

Unstructured Data

The final complexity is the amount of unstructured data in organisations, with analysts estimating that eighty to ninety per cent of any organisation’s data is unstructured, with the volume of data growing at a rate of forty to sixty per cent per year. It is assessed that militaries face the same challenges of managing these unlabelled databases.

LTGEN John Shanahan summarised this problem, then director of America’s Joint Artificial Intelligence Centre stated in a 2019 interview that whilst some said data was the new oil, it is more like mineral ore – a lot of filtering and analysis is required to get the nuggets.

The Solution

Whilst the challenge is immense and complex, the solution is simple. The Australian Army must get their data in order. This can only be achieved through careful study and analysis of the data and information flows on the battlefield, collating and analysing where required, and applying AI applications at appropriate levels to assist in the coordination.

The challenge though, is that the Army is not currently structured to deal with the complexity of the problem. Data and Information are relevant to all aspects of the organisation, and there is no dedicated organisation focused on data and information management across the enterprise.

A potential solution would be to:

Define a Data Strategy that drives tactical change. Before any significant changes in data management can be conducted, the Army should define a clear data strategy, encompassing the data collection, management, and utilisation principles. This strategy is essential, as typically large datasets of assured data are required to create AI applications.

Establish a task focused data management organisation (Data Corps). The Australian Army should look to create a task focused organisation, that can integrate across the army into all units and entities, with an organisational mandate to study, research, and develop solutions to the Army’s big data problem. This organisation should include data scientists, AI specialists, and military personnel with understanding of operational effects. This “Data Corps” could be absorbed into the Royal Australian Signals Corps, or it could be its own separate corps.

Invest in Edge Computing. Edge computing allows devices in remote locations to process data at the “edge” of the network. By processing data as close to where it is generated will reduce the amount of data that needs to be transported, alleviating pressure on military networks (which are both bandwidth constrained and potentially contested by an adversary). What becomes important is understanding what information needs to be transported – for example, a raw video that depicts an adversary system does not need to be transmitted to a decision-maker. Rather, the video can be processed on site and the relevant information (target data) extracted and transmitted. Understanding what constitutes ‘relevant information’ to the decision-maker/commander is the core of the problem.

Conclusion

Data and information flows are the fuel that will feed the strategic deterrent that AI offers. The Australian Army must prioritise understanding and managing these flows to harness the full potential of AI, ensuring timely, accurate, and actionable insights that can decisively influence the battlefield. Establishing a dedicated Data Corps, defining a robust data strategy, and investing in edge computing are critical steps toward this goal.

The challenges posed by the exponential growth of data are immense, but the benefits of overcoming these challenges are equally significant. By adopting a proactive approach to data management, the Australian Army can maintain a competitive edge, improve decision-making processes, and enhance overall operational effectiveness. This strategic focus on data will not only address current issues but also future-proof the Army against emerging threats in an increasingly data-driven world. Now is the time for the Australian Army to lead by example and transform its approach to data, setting a standard for modern military operations globally.

Expenditure on buzzwords, which are well outside army’s traditional remit; come at real cost to army’s ability to actually generate the capability it needs to meet its core role.

Army also, in its current structure directly collects limited amounts of the kind of raw data (outside some key capabilities) this kind of expenditure would justify.

To me, this problem set is defence wide and better served with a DoD civilian workforce (or given time, AI) to service.

"To me, this problem set is Defence wide and better served with a DoD civilian workforce (or given time, AI) to service."

But my question is - how is the AI going to learn what data is important to Army?

We are in the nascent stage of using data within Defence. While there is immense potential from data, it is fair to suggest Army that without investment in a workforce - uniform, civilian, or contractor - to identify, refine, and validate its future data needs we will just continue to overlook opportunities. This is no different to any military technology - we wouldn't leave the development of our next service rifle to someone that has only shot civilian sporting rifles.

The author has done a good job casting a spotlight on a important challenge for Army, and offers some potential types of solutions, acknowledging there is still more work to go. We shouldn't get so caught up on the words, we overlook the message.

The ADF’s Defence Date Strategy is weasel words that has delivered little capability (as did the previous IM strategy); the first line in the strategy vision states “Data-driven insights becoming an embedded part of our work”. The services all seem to do their own IM thing (different platforms, processes etc). Units depend on massive volumes of unstructured, poorly governed data, a records management system that uses a 20 year-old architecture, excel, end of life Sharepoint. A good start would be to turn the Defence Data Strategy into actionable plans that demonstrate value at unit level - not just in Canberra. The ASI on IM needs to be more than just records management and a grab bag of compliance tasks that units are not resourced to deliver.

The article also did a great job in visualizing the sheer volume and metrics of the data in play on a daily basis.