This article is inspired by ongoing discussions about how we can rethink PME. Sci-fi, tabletop gaming and online gaming have proven to be engaging entry points for studying military strategy, ethics and leadership. I wish to contribute to this discussion by proposing artifactual critical literacy as an avenue for critical analysis and deep learning.

Artifactual critical literacy allows learners to tell their own stories and reflect on their own experiences by critically examining ordinary objects.[1] Through engaging activities of varying complexity, learners can develop critical and creative thinking skills, research skills and verbal, written and digital literacy skills. Simultaneously, learners can develop deep understandings about key PME topics such as military operations, ethics, leadership and cultural engagement.

Military context

Artifactual critical literacy is particularly relevant for military learners due to long-standing practices of collecting operational artifacts. Such artifacts might be kit items or uniform insignia, range produce, marketplace souvenirs or gifts from local people. The practice is so widespread that militaries are obliged to enforce regulations to prevent looting, protect culturally significant artifacts and ensure safety. During the 2006 Iraq War, for example, U.S. military members were permitted to collect souvenirs if they did not 'distract them from their duties or put them in danger'.[2] Allowable items included purchased goods with a dated receipt or legally acquired 'common enemy military items that have little or no value'.[3] Prohibited items included munitions, weapons, organic material, personal enemy items and scientific, archaeological or religious relics.[4] In Australia, it is both a civil and military offence to remove range produce from live firing ranges; therefore, participants confirm that they have no range produce in their possession after every practice.

Trench Art

Military personnel not only collect artifacts but repurpose them for functional use or artistic expression. Past and current serving members, for example, have proudly shown me a grenade pin refashioned as a zipper tag (see inset) or an ammunition tin reconfigured as a set of speakers. The practice became known in World War I as 'trench art', but, as Bui points out, can be dated at least back to ancient Greek warfare when tropaion or war 'trophies', made from captured arms and armour, were erected as religious offerings.[5] During World War I, off-duty soldiers fashioned cigarette lighters, letter openers and pens from bullets for personal use or for commercial sale.[6] Decorative items included finger rings made from the aluminium of enemy shells, brooches made from Zeppelin wreckage and artistic works engraved on shells and armoured plate.[7]

Military personnel not only collect artifacts but repurpose them for functional use or artistic expression. Past and current serving members, for example, have proudly shown me a grenade pin refashioned as a zipper tag (see inset) or an ammunition tin reconfigured as a set of speakers. The practice became known in World War I as 'trench art', but, as Bui points out, can be dated at least back to ancient Greek warfare when tropaion or war 'trophies', made from captured arms and armour, were erected as religious offerings.[5] During World War I, off-duty soldiers fashioned cigarette lighters, letter openers and pens from bullets for personal use or for commercial sale.[6] Decorative items included finger rings made from the aluminium of enemy shells, brooches made from Zeppelin wreckage and artistic works engraved on shells and armoured plate.[7]

Not just show-and-tell

A key challenge with artifactual critical literacy is ensuring that learners critically examine artifacts and unpack deep meaning rather than succumbing to superficial ‘show and tell’ activities. Simply asking learners to share souvenirs from their last deployment is unlikely to generate deep enquiry or critical reflection. While such activities can be engaging, as learners share amusing or evocative ‘warries’, simply telling anecdotes, inspired by artifacts, is unlikely to transform how learners think about themselves or the profession of arms. To deepen critical enquiry, learners must examine the changing social and cultural contexts of their artifacts and wrestle with challenging questions to which there are no easy, ‘correct’ answers. By critically examining artifacts, learners could consider the causes, events and outcomes of Australian operations or discuss ethical dilemmas, 21st century geopolitics and cultural engagement. Learners could reflect on leadership or how we express our values in response to changing socio-cultural contexts.

Of course, it is a big leap to go from a small, hand-held object to big picture issues. Applying reflective prompts can help learners travel from simple recall to progressively deeper analysis onto final conclusions. A graduated list of questions could include the following:

Recall

- Where, when and how did I acquire this artifact?

- What was this artifact designed to be used for?

- How do I use this artifact?

- What social contexts/communities has this artifact been used in (home, neighbourhood, work, military)?

- What do I know about previous social contexts/communities?

Analyse

- Why do I use this artifact in this way?

- How does this artifact make me feel?

- Why do I feel this way?

- Did anyone else previously own this artifact? If so, how do I feel about them?

- Why do I feel this way about them?

- Am I a member of, or a visitor to, previous social contexts/communities?

- Would my return be welcomed in previous social contexts/communities? Why/Why not?

- What ethical issues does this artifact raise for me as a soldier?

Conclude

- What does this artifact say about who I am as an Australian soldier?

- Why do I value this artifact?

Learning Activities

The reflective prompts can inspire different learning tasks of varying complexity. An online or face-to-face arousal could be a mystery activity, such as ‘What’s in the box?’ or a ‘What am I?’ close-up photo. Learners could go on a scavenger hunt around the base, finding artifacts or materials that they fashion into artifacts. Or learners could do a digital scavenger hunt, through online museum archives or digital staff rides. Learners could present critical reflections of personal artifacts as an infographic, a wiki page, a Padlet page, a voice-over PowerPoint, a podcast or YouTube vlog. Or how about adding some PME to a virtual morning tea in which learners do an online presentation about a personal artifact?

Artifactual Critical Literacy Sample

To demonstrate how such activities might work, I present a sample Padlet page (see Figure below).

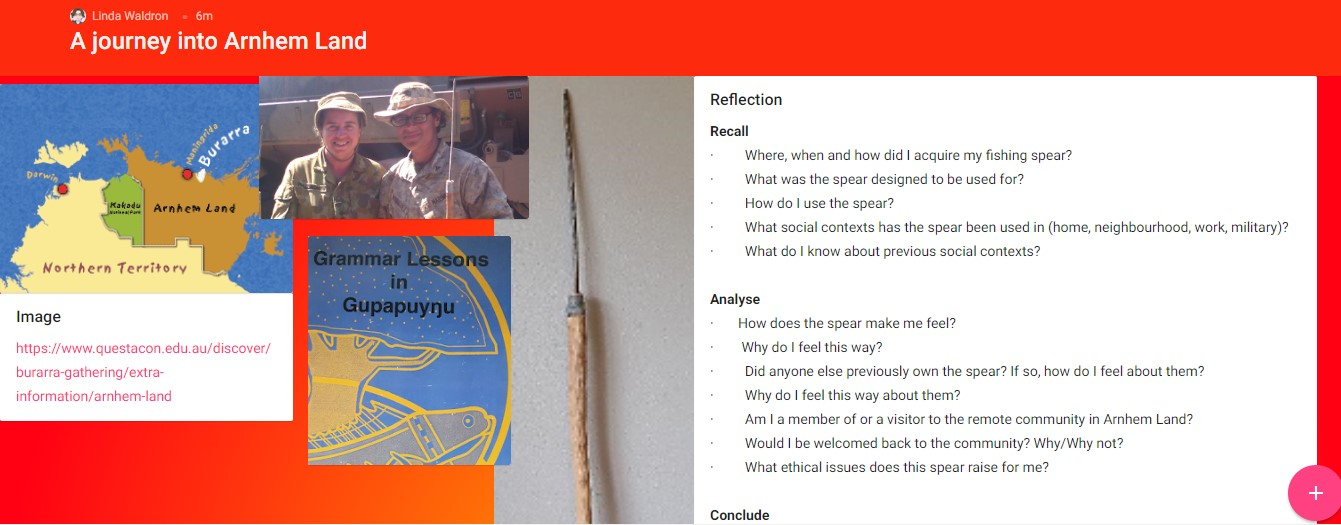

The page records my reflections on an adventure training activity with 8th/12th Regiment in 2017. Soldiers from the Australian Army and Marines from the United States Marine Corps (USMC) travelled to a remote Aboriginal community in Arnhem Land for a week of cultural activities.

On my padlet page, I critically examine a fishing spear that I made while on exercise. The spear represents for me the challenges and opportunities of living and working in a remote community. Recalling the process of making the spear inspired me to think about male and female roles in Aboriginal communities. Our failed fishing attempt in which only one soldier caught a single, inedible fish made me think about environmental knowledge as it was too late in the year for barramundi. I reflected on my relationship with the community members; I was studying Yolngu language at Charles Darwin University so had some linguistic and cultural connections. My ‘skin’ name was ‘Wamuttjan’ which meant I was adopted as a skin-daughter of the community. When fishing and foraging for food, I experienced real-life examples of the Dhuwa and Yirritja spiritual moieties that express harmonious relationships between land, plant life and animal life. I include an image of my grammar book which has a barramundi (Yirritja) and a tamarind tree (Dhuwa) on the cover.

Yet I did not just learn about the Aboriginal community. My battle-buddy was a corporal from the USMC. The activity allowed me to engage directly with a sister-soldier and learn more about the US military: training, career paths, operations etc. On the Padlet page, you can see a photo of us proudly wielding our spears. I was an education officer, embedded with a combat unit, working with a Marine and living in an Aboriginal community. Critically examining my spear thus inspired a range of challenging questions about relationships between Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Australia, about joint exercises, about climate change and sustainable living and about my identity as a female Australian soldier.

Conclusion

Artifactual critical literacy can thus develop deep enquiry, agile thinking and new understandings. Critically examining artifacts of personal significance offers learners engaging and meaningful ways to explore the complexities of the profession of arms. By sharing stories and reflecting on experiences, learners can consider what it means to be a 21st century soldier and how we can successfully adapt to changing operational environments.