Located south of what was formally Lake Huleh in Palestine, Jisr Benat Yakub or Jacob’s Ford, and the more modern bridges over the ford which became known as the Daughters of Jacob Bridge have been a crossing point over the Jordan River for over 800 years. Described as the best known medieval bridge in Palestine, the fords and the later bridges strategic value as one of the few fixed crossing points over the upper Jordan River which enable access to the Golan Heights and to the upper Galilee region is well known.

Medieval Period

This strategic value of the crossing point was recognised by King Baldwin IV of Jerusalem who deduced that holding this key terrain would protect his kingdom from a northern invasion as it dominated the road from Damascus to Tiberias and Acre. He empowered the Knights Templar to build a castle, named the Chastellet, overlooking the crossing. Recognising the importance of such a structure at this crucial point, Saladin laid siege to the incomplete castle which was subsequently destroyed by Saladin in August 1179 during the Battle of Jacob’s Ford. In an attempt to ensure the uninterrupted completion of the castle, Baldwin IV had moved a large force to Tiberias on the western side of Lake Galilee which was a half days march from the castle. This force was designed to reinforce the castle’s defences. However, communication between the castle and Baldwin’s force failed and by the time Baldwin was made aware of the siege, the castle’s defences had been breached, 700 defenders were killed and 800 taken prisoner. By failing to maintain adequate communication to his forces holding the key terrain, Baldwin squandered any numerical advantage his forces could have brought to the battle and increased the vulnerability of the Kingdom of Jerusalem to a northern invasion.

During the second Mamluk period (Medieval realm spanning Egypt, the Levant and Hejaz 1382-1517), a stone bridge over the ford was built in the mid-14th century which was maintained by the later Ottoman Empire. This also included a toll building for taxing travellers who crossed the bridge and a caravanserai (Roadside Inn) on the eastern bank.

Napoleon’s Egyptian Campaign

The importance of the crossing point was also identified by Napoleon in his 1799 Egyptian campaign when he dispatched his cavalry commander, General Murat, to occupy the nearby town of Safad as well as the bridges over the Jordan River to deny the crossing point to the advancing Ottoman forces under the Pasha of Damascus. In this case, a small force of 200 cavalry, 500 light infantry and two cannons denied the Ottoman forces (which some accounts number as high as 35,000 men), the ability to cross the Jordan River and relieve the siege of Acre by the French forces.

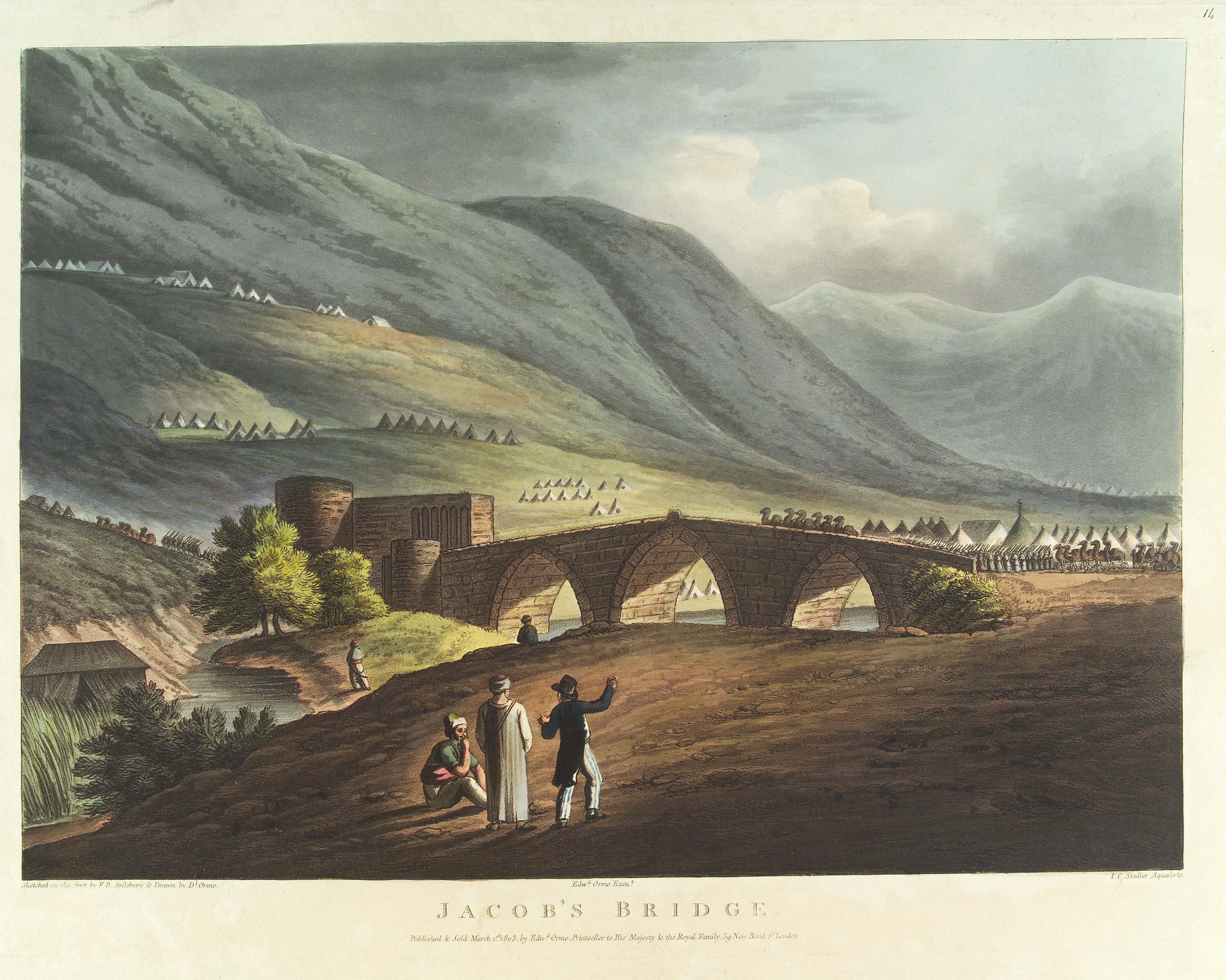

Wellcome Collection / Francis. B. Spilsbury

World War One

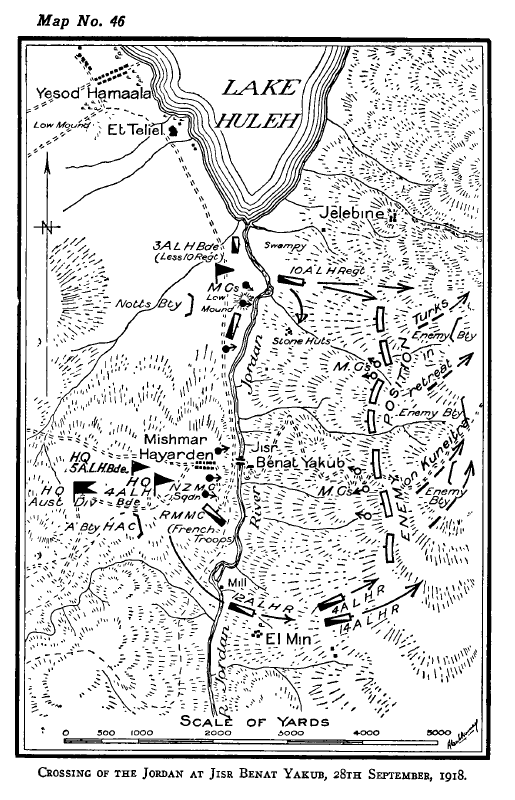

During World War One, the rapid advance of the mounted forces under the command of Lieutenant General Chauvel saw the Turkish forces withdrawing towards Damascus. The Turkish Fourth Army was attempting to concentrate their forces before reaching Damascus and deployed a strong rear guard to protect the bridge at Jisr Benat Yakub. The objective of this force was to delay the Australian Mounted Division for 24-48 hours in order to facilitate a consolidation of the Turkish forces before reaching Damascus and to protect the flank of the 20,000-30,000 Turkish soldiers retreating towards Damascus from Deraa in the south. This rear guard force consisted of approximately 1,000 infantry, several German machine gun detachments and Turkish gun batteries. The defensive line the Turks adopted ran along the high ground to the east of the crossing point which can be seen in the photo below. Using the heights of the ridgeline, the natural obstacle of the steep banks, the marshy ground and boulder strewn areas which hampered horse movement, the Turks were in a strong position along a line 2-3 miles in length which dominated the crossing. Destroying the central span of the bridge was also intended to delay movement by vehicles and wagons across the river.

The image below shows the Jacob Bridge area.

Australian War Memorial / B01297. Shows the Jacob Bridge area.

The Australian Mounted Division lead elements were checked by the Turkish defences on 28 September 1918. However, the 3rd Light Horse Brigade commenced reconnoitring to the north for a crossing point and the 4th Light Horse Brigade did the same to the south. Both brigades were able to force improvised crossing points across the river later that day but were unable to make significant gains during the following night due to the terrain.

However, with mounted forces now across the river near their flanks, the threat of being enveloped was enough to unhinge the Turkish defences and they commenced a withdrawal towards Damascus, covered in most part by a rear guard of German machine gunners mounted in lorries for mobility.

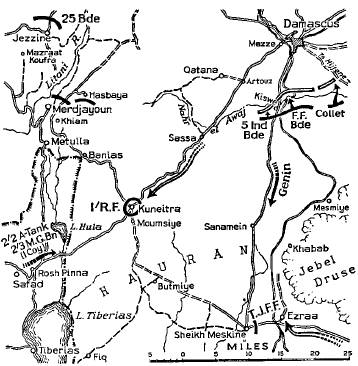

The map to the right details how the advantage of the key terrain was lost by the Turks when they failed to protect their flanks and identify likely secondary crossing points that the Light horseman may use and plan an appropriate defence or response. Of note, the crossing point made by the 3rd Light Horse Brigade was only 500 yards south of the impassable swamp area of Lake Huleh. A small gap but significant in its outcome for the Turkish rear guard.

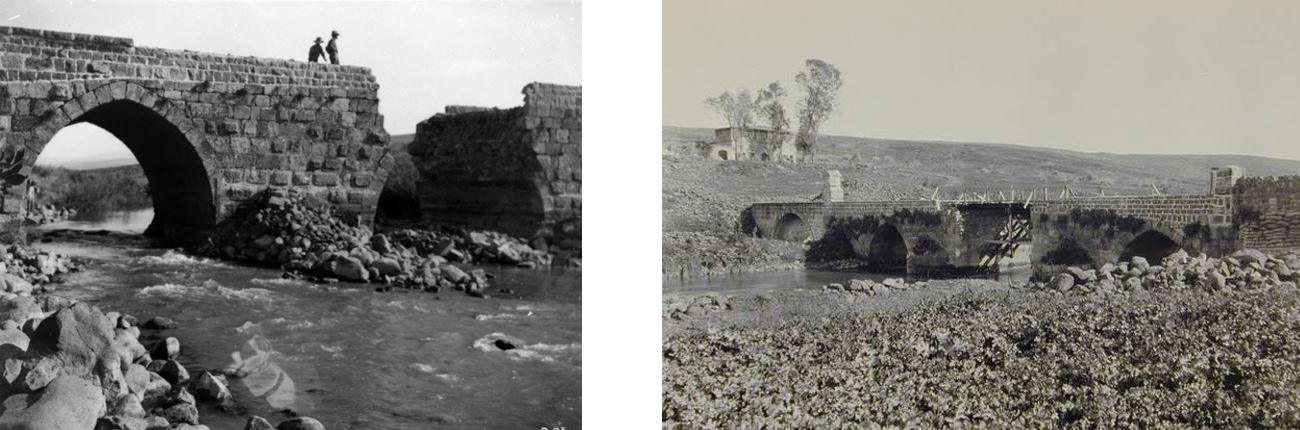

The broken span of the bridge was repaired in a number of hours by Australian Engineers and a party of Light Horseman improved the ford which allowed wheeled transport to use the crossing point in the early afternoon of 29 September 1918. Dropping all three spans of the bridge may have provided a more significant delay to the wheeled transport of the Australian Mounted Division. The result of the rear guard defences being unhinged was the destruction of the Turkish Army before it was able to consolidate its defences near Damascus. The photos below show Yakub Bridge being inspected by Australian soldiers after the Turkish retreat and after repairs had been completed.

Australian War Memorial / C53689 & C321174

World War Two

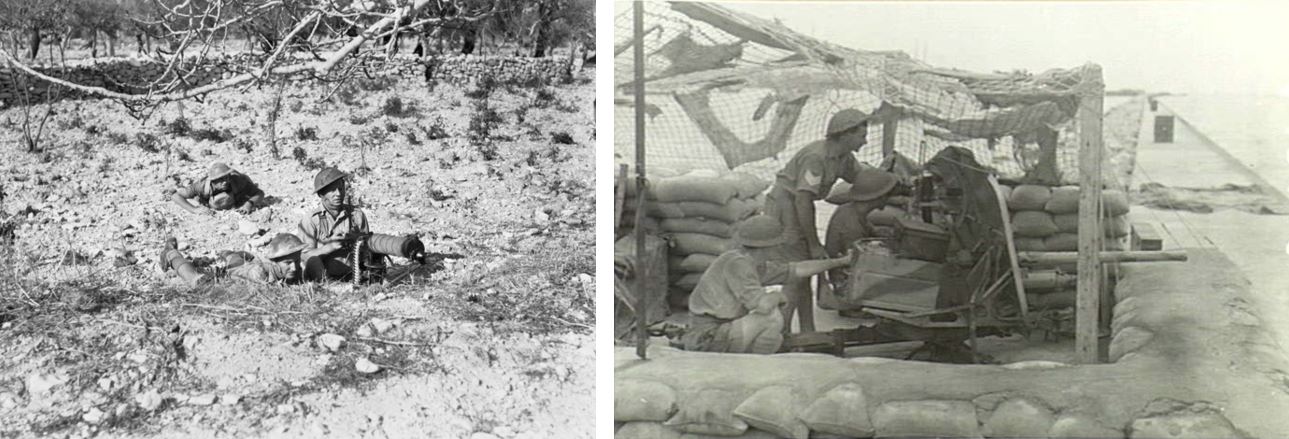

The Syria-Lebanon campaign in 1941 once again highlighted the Daughters of Jacob Bridge crossing as key terrain. The old stone bridge had been replaced by a more modern bailey type bridge in 1933. In June 1941, the Vichy French forces conducted a general counter attack on three axes. The centre axis was directed towards the town of Kuneitra which is south west of Damascus and only 25 miles from the crossing point. The British and Commonwealth forces were of the belief that this thrust towards the crossing point would undermine their northern defences in the vicinity of Merdjayoun and jeopardise the whole campaign. With light tanks and carrier mounted machine guns and 2 pound anti-tank guns as the main anti-armour deterrent, the British were not in a good position to fight on equal terms with the 27 medium tanks, 12 light tanks, 12 armoured cars, 2 field guns, mortars and 1,500 infantry that comprised the Vichy French forces of the central axis which were focused on the crossing point.

The Vichy French quickly overran and forced the surrender of the under strength British Fusilier battalion that had been holding Kuneitra. After having left the crossing point guarded by only a small horse mounted cavalry unit, the commander of the Australian 7th Division, ordered the reinforcement and guarding of the bridge crossing, which was conveyed to the commander of the Australian 2/3 Machine Battalion, Lieutenant Colonel Blackburn, VC, who efficiently moved his available force south from the Merdjayoun sector to the vicinity of the bridge during the night and had the defences set by morning. The defence of the bridge comprised a machine gun company and two troops from the 2/2 Anti-Tank Regiment.

Australian War Memorial

As previously seen in the less than enthusiastic retention of the key terrain by the Turkish forces in the previous war, the Vichy French were equally lacking the drive to capture the key terrain and they remained in Kuneitra despite the efforts of the Australians to draw them out of the town and into the anti-tank engagement areas. They remained in the town until they were expelled two days later by a British infantry battalion attack. The point to note in this instance is that the key terrain of the crossing point would have forced a canalisation of the Vichy French armour into prepared engagement areas where the anti-tank guns would have most likely prevented the Vichy French from crossing.

The strength of the Vichy forces arrayed against the Australians should have been overwhelming if they retained the initiative and enthusiasm to maintain the attack. However, the crossing point would have provided the anti-tank gunners and the supporting machine guns a marked advantage by denying the enemy the ability to manoeuvre and use the terrain to their own advantage. The long range ammunition in use by the Australian machine guns (4,000m) may have also lead to the dislocation of the infantry from the armoured force which in turn would have further hampered the successful armoured assault to capture the crossing. Retention of the crossing was a key concern for the allied defences and the possible advantage of capturing and exploiting the crossing point was not acted on by the Vichy French.

The Yom Kippur War of 1973

The 1973 Yom Kippur War involved simultaneous assaults on Israel by Egypt in the Sinai and Syria in the Golan Heights. The primary objectives of the Syrian advance was to capture the Golan Heights and reach the Jordan River in under 36 hours. This would serve the purpose of restoring Arab military pride and restoring the pre-1967 Six Day War borders. The assault commenced at 1400h on the afternoon of 06 October 1973. The afternoon assault timing was a coordination timing insisted on by the Egyptians that did not work in the Syrian’s favour but the initial gains were impressive, especially in the central southern regions. Two Israeli tank battalions were deployed in the northern Golan and one tank battalion in the central and southern Golan.

The Syrian’s advance in the centre broke through the Israeli defensive lines at the Kuneitra Gap and the Rafid Gap in the south. This allowed the second echelon attack forces to penetrate towards the crossing points at the Jordan River which threatened to cut off the Israeli forces in the northern Golan and block their reinforcement. The Syrian advantage in mounted night fighting equipment enabled the Syrian advance to maintain pressure on the Israeli’s during the night. The Israelis were forced to use flares or searchlights to engage the Syrian armour. 7 October 1973 saw the Israeli forces struggling to maintain cohesion as they effectively fought a delaying action until their reserve forces could be activated. The Syrian’s believed that it would take up to 36 hours for the Israeli’s to activate their reserve and reinforce the beleaguered Golan front.

This belief, combined with the Syrian logistic train that was struggling to keep up with the tempo, a failure to reinforce the success of the southern advance and a centralised command system that required strict adherence to orders with no latitude for initiative saw the Syrian advance stall late in the afternoon of 07 October 1973. Some reports put the lead Syrian tank units as close as a 15 minute drive from the Jordan River at the Jisr Benat Yakub crossing. The Syrian units remained static for the evening before they recommenced the advance in the morning of 08 October 1973. However, the Syrians found that the key terrain of the crossing point had been occupied by the Israelis who had mobilised their forces far quicker than anticipated. The Syrian advance was checked as the Israeli reserve forces flowed across the Jordan River. This resulted in the Syrians failing to capture and use the key terrain to their advantage by out flanking the northern Golan sector and deny the Israeli reinforcements the routes they needed to reinforce the hard pressed northern Golan units. This failure led to the Israelis counter attack driving deep into Syria and to within artillery range of Damascus before the ceasefire came into effect.

The image below is a current day photo of the Bailey Bridge from the 1940s. The stand of trees in the middle of the photo is the site of the old Caravanserai.

Google Maps / The Bailey Bridge in the 1940s; the stand of trees in the middle of the photo is the site of the old Caravanserai.

By no means can it be said that the war would have been won if the crossing points had have been seized on 7 October by the Syrians. The Israelis certainly had advantages in other areas, such as superior individual and unit training, compressed logistic trains, superior command and control structures and a well-developed reserve mobilisation structure. It could; however, be argued that these advantages could have been reduced as the Israelis ability to project these advantages into the northern Golan front would have been nullified if the Syrians held the crossing point over the Jordan River.

The centralised command system employed by the Syrian’s failed to take advantage of another principle of war: flexibility. The Syrian command system lacked the flexibility for commanders at Brigade and below level to take advantage of the unexpected lack of Israeli resistance in the southern sector and to exploit this opportunity by seizing the bridge.

Depending on the impact that the seizure or the retention of the crossing point at Jisr Benat Yakub would have had in either the First or Second World War or the 1973 Yom Kippur War, it may also be described as decisive terrain if the impact could have been extraordinary.

Offensive actions are conducted in order to meet a number of outcomes. These include the seizure of key or decisive terrain and to seize, retain or exploit the operational initiative by preventing the adversary from concentrating, consolidating or regrouping. By all accounts, the Syrian attack failed to meet these outcomes and this directly contributed to the failure of the mission. The failure of the Turkish forces in the First World War to retain the key terrain denied them the time and space required to organise a consolidation of their forces and accelerated their destruction by Chauvel’s mounted forces.

The use of mission command and the ability of junior commanders to exploit opportunities and make tactical decisions such as seizing key terrain in their area of operations in accordance with their commander’s intent will increase our own decision superiority and force the enemy to comply with our scheme of manoeuvre. It should also be noted that key terrain is not always highlighted at the higher level. Junior commanders must still conduct an appreciation of the geography in their specific area of operations and determine which areas of the geography provide them a marked advantage and define them as key terrain. In some circumstances, this seizure or retention of this terrain will also be a decisive event which is directly linked to the successful completion of your mission.

This case study of the crossing point at Jisr Benat Yakub has identified several failings on both the defenders and attackers behalf when conducting their operations in this particular area that may be beneficial for your future military operations planning. Commanders at all levels must consider the geography and what terrain advantages they can use to seek a marked advantage over the enemy.

Thanks for your comment and I hope you enjoyed the article. I always welcome critique of my work as I make no claims on being the expert and sometimes mistakes are made.

However, in this case the two Light Horse Brigades involved in the action at Jisr Benat Yakub Bridge, 3rd Light Horse and 4th Light Horse Brigades were part of the Australian Mounted Division at this stage of the War. The 3rd Light Horse Brigade was originally part of the ANZAC Mounted Division when it was formed in March 1916 but transferred across to the Imperial Mounted Division when it was formed in January 1917.

The Imperial Mounted Division had been renamed the Australian Mounted Division in July 1918.

Therefore, at the time of this action in September 1918, the correct name for the division of the units involved was the Australian Mounted Division.

In addition, the Wikipedia links below detail the time lines for the ANZAC Mounted and Australian Mounted Divisions as well as the Brigades which comprised them.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ANZAC_Mounted_Division

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Australian_Mounted_Division

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/3rd_Light_Horse_Brigade

Regards,

David.