It was a popular belief in the past that to build a soldier, we must first break the individual down and re-build them, removing all signs of the civilian, and constructing a warrior. Although this warrior ethos seemed to work effectively 20-30 years ago, its repressive nature is arguably ineffective in today’s Army. During this paper I will suggest that it takes both cognitive and emotional intelligence to be an effective leader in a modern military, further; draw a link between emotional intelligence and resilience.

Leadership in the Army’s past was exercised within a draconian rigid hierarchy. Though emotional intelligence had its place, it was not a ‘leadership skill’ that was recognised or promoted. The mere mention of emotional intelligence would more likely have been met with ‘eye rolling’ and claims of adopting a ‘touchy feely’ approach to soldiering. However, the modern Army has proven more proactive in understanding the developing science of emotional intelligence and its possible applications. In fact, this approach has taken a foothold as a valued leadership skill, and is considered a way forward.

The Army has become smarter in the way it leads, educates and develops its leaders (especially as the concept of emotional intelligence evolves), transforming concepts of command and leadership and applying them diligently in order to improve leadership methods and techniques.

Emotional intelligence defined

'Emotional intelligence is the capacity for recognising our own feelings and those of others, for motivating ourselves, and for managing emotions well in ourselves and our relationships'. Emotional Intelligence 1995 by Daniel Goleman

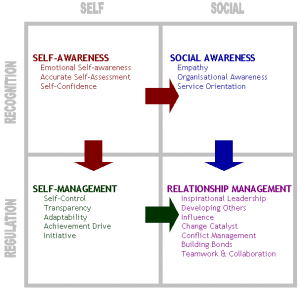

Many experts within the field of emotional intelligence have developed leadership requirement models, based on attributes required for a person to be successful in the art of leadership.

Figure 1: Leadership Requirements Model, Daniel Goleman, 2000

As depicted in Goleman’s model (Figure 1), there are four leadership requirements that should be fostered through improved emotional intelligence:

- ability to perceive emotions in oneself and in others

- ability to use emotions to facilitate thinking

- ability to understand emotion, emotional language and signals conveyed by emotion and

- ability to manage emotion so as to attain specific goals

These same attributes are equally important in the military. Leadership is the process of influencing people by providing purpose, motivation and direction whilst encouraging individuals to works as a team to accomplish the mission. Most would agree that the Army’s leadership attributes align with Daniel Goleman’s leadership requirement model. Leadership education, and development of these attributes start during initial training in Defence; whether someone steps forward to take the lead or is appointed, from the moment we put on the uniform, we are exposed to the values, ideals and skills required to be an effective leader.

What is not understood at the onset of initial training is how emotional intelligence effects performance throughout a soldiers career. Unlike other types of intelligence, emotional intelligence is not static - It can be continually built and developed over time through experience and mentoring. However, while some must consciously work to develop their emotional intelligence, others seem to have a natural ability. It could be argued that the Army is not doing enough at pre-enlistment to assess a candidate's emotional intelligence, which could provide a measure of their resilience and potential as an effective leader. The process of assessing cognitive intelligence (IQ) simply provides an assessment of a person's ability to process and retain information. It does not consider their ability to emotionally deal with that information and act accordingly.

It is commonly understood by western militaries throughout the world and academics in the field of military leadership, that intelligence is more than cognitive. This is not to say cognitive ability is not important. To be a successful leader you need expert knowledge and skill in your chosen field to remain current, relevant and competent; however the art of leadership, especially in contemporary times requires a more creative and innovative approach.

Emotional intelligence embedded in leadership training can create positive effects for command and relationship management. This in turn could prove particularly helpful when dealing with operational challenges and post-adversity impacts, such as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). This is not to say that soldiers will not be affected by trauma, only that those who are provided with emotional intelligence training will have more resources to draw from during the recovery process.

Emotional intelligence – An important factor in resilience

PTSD can have a debilitating long-term effect on the individual and can negatively impact the Army’s performance and reduce its manpower.

'Resilient leaders can recover quickly from setbacks, shock, injuries, adversity and stress while maintaining their mission and organisational focus' LTCOL (Ret) Gerald Sewell (USAR)

Published in the US military review, the ‘Emotional Intelligence and the Army Leadership Requirements Model’ written by Lieutenant Colonel Gerald F. Sewell, recognises the necessity of building resilience training into US Army programs. The purpose of this training is to firstly enhance resilience, but also to decrease susceptibility to PTSD, decrease incidence of undesirable destructive behaviors and create a greater likelihood of post adversity growth and success. The five dimensions of their resilience training are:

- Physical - Performing and excelling in physical activities that require aerobic fitness, endurance, strength, healthy body composition, and flexibility derived through exercise, nutrition and training.

- Emotional - Approaching life challenges in a positive, optimistic way by demonstrating self-control, stamina and good character with your choice and action.

- Social - Developing and maintaining trusted, valued relationships and friendships that are personally fulfilling and foster good communication, including a comfortable exchange of ideas, views and experiences.

- Family - Being a part of a family unit that is safe, supportive and loving and provides the resources needed for all members to live in a healthy and secure environment.

- Spiritual - Strengthening a set of beliefs, principles, or values that a person has; beyond family, institutional and societal sources of strength.

In addition, studies in the field of psychology suggest that leaders with a high level of emotional intelligence may prove vital in stressful combat situations where cognitive function is constrained. Soldiers in these situations are difficult to access and manage; therefore a leader’s cognitive intelligence as a leadership strategy becomes less effective. Truly effective leaders are forced to use non-cognitive, emotional intelligence skills to maintain control, assess the challenges, take decisive action whilst building trust and being a source of strength.

Emotional Intelligence Training

Certainly, any training program needs to start somewhere. Assessing potential recruits is an obvious beginning, complemented by continual emotional intelligence education throughout a soldier’s career. Achieving reliable pre-recruitment assessment may prove the greatest challenge and is certainly recommended as an area for future research and development. Further, if a soldier is deployed on operations, continual theatre based emotional intelligence training may prove invaluable. For example, critical incident stress management teams could be trained to respond to stressful incidents and assist in the management of members after exposure to a traumatic incident.

Decompression after operational service is also a concern. A 'mandatory period of service' following a deployment would complement the current decompression policy. In short, not permitting separation for a period of time following operational service would provide an opportunity for emotional growth through ongoing training and support (such as developing coping strategies and resilience), potentially decreasing the likelihood and impact of long term mental health illness.

With regard to ongoing training, there are programs that exist already; they simply need to be reinvigorated and built upon. Programs such as adventure training, which by design apply war like stresses and emotions, are an excellent method of exposing personnel to their own emotional intelligence, promoting emotional self-awareness and familiarity with feelings, stressors, weaknesses and strengths.

Leadership Intelligence

Without doubt, emotional intelligence is a key to real leadership success, however, just as cognitive intelligence is not the only solution, nor is emotional intelligence on its own. Through the application of both, one can derive 'leadership intelligence' which allow individuals to demonstrate the relevant job knowledge and skills, while also demonstrating an understanding of emotions in oneself and others. Leadership intelligence allows us to switch between leadership styles to suit a given situation. It is safe to say that leaders who achieve the best results use an eclectic approach, providing an appropriate and measured response to any situation.

Conclusion

The Australian Army is quickly embracing the importance of emotional intelligence. Resilience and its potential to curb the instances and impact of post-traumatic stress disorder have received considerable air-time recently; however, some still roll their eyes and scoff at what they perceive as a touchy-feely concept. Emotional intelligence does not mean a softening of standards, nor the degrading of discipline, conversely, it means a more considered, balanced and educated approach where there is an understanding of the second and third order effects.

The modern soldier is placed under enormous pressure professionally and emotionally to operate is today’s complex environment. Training soldiers on how to develop self-awareness, awareness of others, emotional management strategies and techniques to handle stressful situations should be at the forefront of any commander’s thoughts.

Further developments in assessment at point of entry and ongoing education in the area of emotional intelligence is unquestionably the way forward.