In November 2017 Commander Forces Command (COMD FORCOMD) wrote to his Formation Commanders regarding the implementation of Plan KOTINOS seeking to optimise the way Army employs its Physical Training Instructors (PTIs). With approximately 13% - 18% of FORCOMD unfit for their primary Employment Category Number (ECN) or function on any given day, a review into how to best employ PTIs is certainly justified. Noting the Chief of Army (CA) provided strategic guidance in 2019 to ‘look for ways to simplify the Army’, the purpose of this article is to contribute to this discussion and offer a proposal for an optimised PTI capability.

Background

Firstly, it’s important to consider the background behind the current PTI structure and training model. The PTIs were brigaded into 1 Close Health Battalion (1 CHB), and to a lesser extent 2 General Health Battalion (2 GHB), as part of the 2013 Combat Health Restructure, with pockets of PTIs remaining posted to Special Operations Command (SOCOMD) and Training Establishments. The original purpose behind was twofold: firstly it aligned with the deployable concept of a PTI, and secondly it incorporated PTIs into a broader intent of centralising health capabilities in order to increase clinical governance and employ health assets more efficiently across Army. Units would simply request PTI support for relevant PT sessions, training blocks (i.e. Army Combative Program, Basic Fitness Assessments, etc) or deployments; PTIs could then be assigned tasks as-needed, creating a central pool in each manoeuvre Brigade location who could be ‘plug and played’ as necessary to optimise efficiency. This has been reinforced through the development of habitual relationships between individual PTIs and their assigned Unit.

Whilst this may appear as a feasible course of action (COA), I would argue that the injury rate of our workforce is a reflection of the unintended consequences of brigading of PTIs. Moreover, this has resulted in a complex structure that lacks flexibility, has created an opaque career pathway, and restricts PTIs from achieving their mission. Anecdotal feedback has reflected that there is room for improvement in how we best employ and retain this capability. Take for example the habitual relationship of PTIs; whilst at first this appears a sound solution to supporting our workforce efficiently, it also means that PTIs can be swapped and changed due to any number of circumstances. This means that PTIs do not have ownership of a Units’ physical training or rehabilitation, and it is subsequently difficult to develop and deliver an enabling capability tailored a Unit so as to optimise raise, train and sustain (RTS) functions in development of robust and resilient personnel. Similarly, it distances PTIs from those undergoing rehabilitation; thereby losing oversight and ownership of ensuring optimal rehabilitation and force health preservation.

This has also had additional repercussions in relation to the career progression pathway of PTIs. If all PTIs are essentially a ‘plug and play’ asset for PT sessions and tasks, aside from time and a few career courses, how do you differentiate between a Corporal (CPL) and a Sergeant (SGT)? What opportunities exist to progress professionally if we are using them for largely the same purposes regardless of rank? Whilst experience should certainly be a requirement for any career progression pathway, there is now an opportunity to further align career progression with professional education and upskilling, as well as improved delineation in roles and responsibilities, each of which will have tangible benefits to the resilience and health of our soldiers.

Proposed Solution

Given the recent focus on human performance, evidence-based best practice, and the PTI capability in general, the current environment presents an opportunity to seek to optimise our PTI workforce. PTIs do not just run PT sessions; they are experts at human performance, educating our workforce on healthy lifestyles and ensuring optimal rehabilitation outcomes. To optimise our PTI workforce, I would propose the following steps:

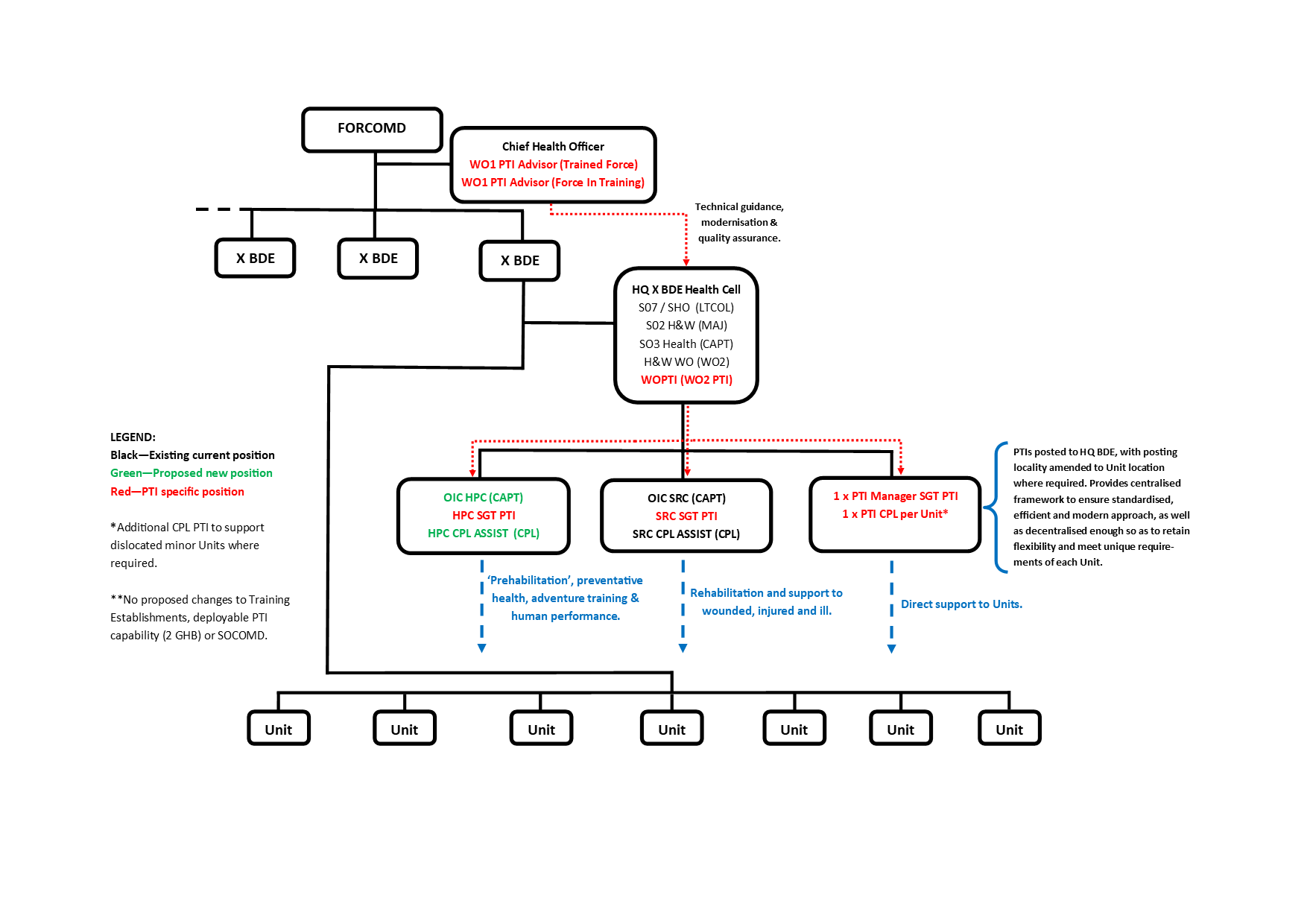

Step 1 - Decentralise the PTI workforce. The first step is to post PTIs to each Formation HQ, from which they can then be assigned to tasks as the relevant Brigade (BDE) sees fit. For decentralised Formations, PTIs can remain posted to the HQ BDE, but posting locality amended to suit. This will provide both the ability to align training loads, professional development and governance centrally, whilst also providing flexibility and ensuring optimal support to each unit. This would also optimise PTI capability in the operational environment. The current structure of PTIs embedded as part of Brigade Support Platoons (BSPs) is impractical; given that the holding policy of a BSP rarely exceeds 5 days, there is limited scope for a PTI to conduct rehabilitation physical training. Under the decentralised workforce model, a move to PTIs being held under HQ BDEs would enable flexibility in their application of their capability to suit the operating environment. Additionally, consideration to expanding their role to something similar to the UK model, where they are deployed as the CO’s personal security in the field environment, may also offer an optimised capability in both the barracks and operational environments. A proposed structure for a manoeuvre Brigade is outlined in Figure 1.

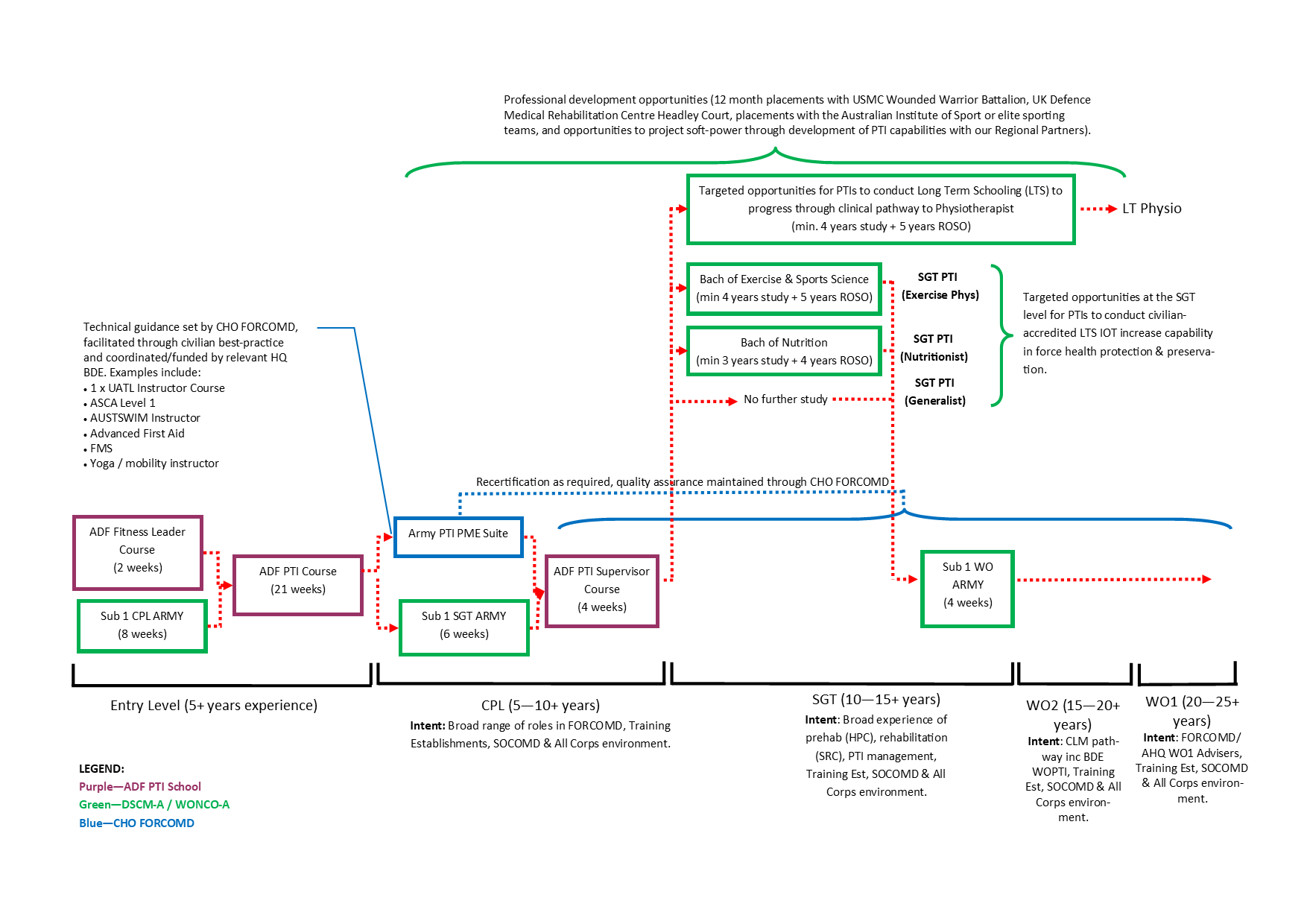

Step 2 - Develop best-practice PTI career progression. Next it is important to develop a PTI-specific suite of PME courses that focus on best-practice in physical training. Each course should be integrated with evidence-based commercial best-practice such as Australian Strength and Conditioning Association Levels and Functional Movement Systems packages. Similarly, packages should include training on the Australian Defence Force (ADF) Medical Employment Category (MEC) System and rehabilitation, Unit Adventurous Training Leader (UATL) Instructor courses and alternative mobility courses such as yoga in order to optimise PTI capability for the benefit of soldiers. The training modules should have a lesser focus on the deployable field environment and more focus on the realities of their profession.

At the senior non-commissioned officer (SNCO) level, PTIs should be afforded the opportunity to conduct Long Term Schooling to increase their capability. This could include the development of PTI specialisations such as SGT PTI (Nutritionist) and SGT PTI (Exercise Physiologist) that are linked to civilian-accredited pathways so as to ensure best-practice, incentivise retention and optimise ability to conduct force protection and force preservation.

Similar to the UK, PTIs should also be afforded the opportunity to progress down a clinical stream through formalised Long Term Schooling opportunities for PTIs to develop into Physiotherapists. The command, leadership and management (CLM) pathway would be further reinforced and clarified through Step 1 and the enabling of Formations to develop appropriate governance mechanisms and effective human performance frameworks.

Step 3 - Develop opportunities for PTI professional development. Finally, PTIs should be encouraged to seek out and exploit opportunities for further career progression and Army capability such as year-long exchanges with foreign forces (such as the Wounded Warrior Battalions in the USMC or with the newly established UK Defence Medical Rehabilitation Centre Headley Court), placements with the Australian Institute of Sport or elite sporting teams, or opportunities to project soft-power through development of PTI capabilities with our Regional Partners.

Conclusion

PTIs are a valuable asset to Army and there now exists an opportunity to optimise our workforce through reinvigorating the PTI capability. Recent initiatives such as the Human Performance Framework Trial highlight pockets of excellence, and we should now build on this through a large-scale structural and cultural change to align PTIs with capabilities that will provide Army with the opportunity to develop best-practice operational enhancement. This should include an organisational structure that supports evidence-based technical guidance and a modernised employment category that reinforces best-practice, provides a clear career pathway and supports retention of a capability that directly supports the strength of Army – its people.