Click here to download a printable copy of this article.

Much of this article will talk about Sea Series and Exercise (Ex) HAMEL 18, but it also draws upon my experiences and of those around me. I certainly do not profess to have the perfect solutions and many of these thoughts are based on what I would do differently if I had the chance again.

Understand Command versus Control. It’s not as straight forward as you think. Everyone has an opinion on how this looks and essays are still being written on it. Talk to your Commanding Officer (CO) and find out what they think your threshold for decision making is. At the start of his time in command, my CO told the Battalion that ‘trust’ was our centre of gravity. He talked about many ways in which trust was important for the Battalion, and this rung true for me during my time as his Operations Officer (OPSO). Ex SEA RAIDER and HAMEL 18 saw the CO and I spend very little time in the same location. At one point he was commanding an amphibious air mobile raid off the coast of Shoalwater Bay, whilst I was left with the rest of the Battle Group at the other end of the joint task force area of operations conducting security operations. At all times I knew that I was trusted to work within his intent and that it was my responsibility to keep him informed of what was going on. Getting a good intent statement from your CO makes your life so much easier. If you are in any doubt as to what your CO’s intent is, address it quickly or you will be irrelevant.

Use the Headquarters Senior Soldiers effectively. Traditionally, one of the most under-utilised resources in a headquarters is the Operations Warrant Officer (OPSWO). Our OPSWO had tactical command of the Headquarters. He issued us deployment and step up orders and sighted the Headquarters in conjunction with the S6 (Communications Officer) and myself. He was responsible for security and receiving any callsigns that came into the Headquarters’ location. Small things he did, like policing light discipline and reminding us that tents weren’t soundproof, kept us honest. He was the sounding board for planning and was tasked with picking holes in anything to ensure we had our bases covered. He was also the Company Sergeant Major (CSM) of the Headquarters; gripping up the many cells, specialist platoons and enabling teams that made up a very large headquarters. We divided it up pretty well: I talked about the Battle Group and how it would operate and he talked about the Headquarters as a stand-alone sub unit.

Figure 2. The Operations WO delivering orders for the Battle Group Headquarters deployment on HMAS Canberra during Ex SEA RAIDER 18.

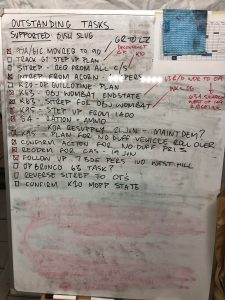

Think about your Headquarters set-up – practice makes perfect. I have seen everything from a handful of dismounted staff officers in a trench with a radio, through to large-scale tent set-ups that would fill a footy field. I can safely say that I don’t think there is a perfect solution that caters to all environments and situations. The key message I would share is that putting a tent up is worth it if you have time and the threat allows. We found that our functionality and ability to coordinate effects greatly improved when we were all operating from desks in the same space. When the tent wasn’t up, we relied on three protected mobility vehicles (PMVs) reversed into a cruciform: These were the current operations (ops) vehicle (0A); our combat signals regiment unit node vehicle (K1) (to speak to brigade headquarters and the amphibious task group); and the joint fires and effects coordination cell vehicle (G1). I put myself in the middle of those three vehicles and was able to coordinate the captains that were setup in each. I felt more like the conductor of an orchestra than a tactical staff officer, but it worked really well. Using whiteboards helped for incident tracking and keeping on top of things when there were several big things happening at once.

Figure 3. Even in a digital world ‘whiteboarding’ works – Current Ops task board Ex HAMEL 18.

Whatever you decide to do, practise it! When the OPSWO tells you that they want to take all of the Headquarters staff out and practise setting up – do it and force everyone to do it with you. There is always an excuse not to do it.

Figure 4. Battle Group Ram 0A - the current operations car on Ex HAMEL 18.

Fight for comms – never give up! Our biggest battle was fighting for communications, but it was worth it. The battle management system (BMS) drastically improved our situational awareness. It ensured excellent control measures and location tracking, especially with other brigade units. We had BMS as our primary means of communication. All battlefield commentary from company second in commands (2ICs) was on BMS chat using the reports and returns functions. The Battle Group Command voice net was reserved for sub-unit commanders and the CO to talk directly with each other. This was policed by the Battle Captain. I found that the only people with negative comments about BMS were those that didn’t understand it, had never used it, or didn’t have it working. Whilst our signallers were all trained in the technical aspects of setting up the network, most of our officers and senior non-commissioned officers (the operators of the system) were taught by peers or in a soldiers' five environment. Have one Primary, Alternative, Contingency, Emergency (PACE) plan and have BMS as your primary means. Having a digital and voice PACE creates ambiguity around how you intend to communicate as an organisation. If in doubt, stop and get comms. During a battle group step, whilst the companies were on the move, we lost comms. Don’t accept that. Stop the patrol, get comms and get situational awareness back. In 2018 there is no excuse to not have a method of communicating with callsigns. Your signallers and S6 are well trained and know their stuff. Give them the space to think and let them tell you how they can make it work.

Figure 5. Finding what is going on during Ex SEA RAIDER 18.

Use the people not their title. We all know everyone has different strengths. Work out what your team is good at and play to it. My best BMS operator was an infantry lance corporal. He was part of my current ops team and drove the BMS for the main television in the Current Ops tent. He was mainly self-taught on BMS and learned the rest from signallers. It was this lance corporal who processed 9 liners and updated the boundaries when there was a change. Giving people ownership in their part of the team, and listening to their thoughts about how we could make it better, made the difference. Everyone was invested in the Battle Group’s success. Asking the question, 'What do you think?' from each battlespace operating system (BOS) or team, was really powerful. It stopped things being missed, but it also created an environment of ‘best idea wins’. Doing this lets everyone have a voice and feel like they are contributing, which leads to people actively participating and adding value.

Figure 6. Battle Group Ram Headquarters Main, Ex HAMEL 18.

Stop, think and give orders. It doesn’t always go to plan. The situation changes. The enemy can mess with your plan or an opportunity can present itself. Conducting a staff check with the BOS leads at moments of uncertainty will help regain the initiative or exploit that opportunity. It is not just your responsibility to work with the CO’s intent and deliver battle group orders to achieve that; it is your responsibility to give orders to the Headquarters so they know how their BOS will support the CO’s plan. Avoid ambiguity. Use SMEAC (situation, mission, execution, administration & logistics and command & signals) and correct mission verbs. When things get busy and chaotic, that simplicity is needed all the more. Have a bias for action. This comes back to trust. If an opportunity presented itself and a call needed to be made quickly, I felt safe in making that call as long as I was working within the CO’s intent. I always fought to inform the CO of any decision I made on his behalf, but sometimes it was after the fact due to the situation we were faced with.

Figure 7. When it all goes wrong, get BOS updates and give orders – Battle Group Ram HQ, Ex SEA RAIDER 18.

'Have a hot feed and get your head down' – get rest and make your team rest, too. You are less efficient when you are tired. Obvious, right? Yet we can often get it wrong and a headquarters can be a competition of who is the busiest or who’s working the most hours. We also have some highly motivated people, who you will need to force to get rest. There were times when I had to order people to go get sleep. Weight your effort on where you need to be at your best. Have the confidence to get sleep when you can. It makes you more capable at your job, but it also sets a good example for the rest of the Headquarters. You set the culture of the team. Value the quality of work someone produces over the amount of time they stay awake. Think ahead. When do you need your different teams to be fresh and focused? If your future ops captain is working through the night on a short notice plan, send the current ops captain to get sleep. They are likely to be the one executing it on the net in the morning. As with any leadership role, you are a talent manager. Periodically I would quiz people on when they last had a hot meal and when they last slept. It prompted them to do the same with their teams and created a culture where that was important and something I wanted them to do.

Figure 8. Your team will have sleepless nights when they need to. So, get them rested when they don’t.

Have a battle rhythm and stick to it. Always work to the Combat Brigade Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for your reports and returns. We simplified our battle rhythm. We established that we needed something that worked even when we were on the move, which was often. We reduced our battle rhythm to a morning ops sync and an evening Commander’s Update Brief (CUB) for all key staff. Then intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) and joint effects working groups would happen as required in and around the S5 (plans) cycles. The more complicated your battle rhythm is, the more that will fall off when everyone is busy, e.g. you’re mid-step up or when the Battle Group is attacking an objective. Keep it simple and make it happen.

Make friends with your higher HQ and keep them in the loop. Whether it be our brigade headquarters or the amphibious task group headquarters, we would give them a ‘contact wait out’ for anything we had going on. Keeping the higher HQ in the loop early lets them have a better read on the situation, keeps them from chasing you for information, but also allows them to offer or prepare assets they may be able to give you in support. When it got really bad, a voice over Internet Protocol (VOIP) phone call to the Brigade Major and talking it through really helped. Having a good relationship early on allows the human factor to work. Something as simple as tone of voice or the way we word things helped me to explain our situation and remove any confusion. Digital communications still reigned supreme and gave us the best control measures and coordinating instructions we could hope for, especially in a combat brigade structure. But, every now and then, it was complemented by human interaction over the phone. Don’t let your higher headquarters pressure you into putting too much pressure on the callsign dealing with a situation on the ground. That also requires you to temper your eagerness to know what is going on straight away. That said, the door swings both ways, and you should demand reporting from your ground callsigns in a timely fashion. Finding the balance of what that looks like takes practice and after-action reviews to get it right. It’s easy to become frustrated with your higher headquarters, but if you are not giving them anything to work with then you are not adding value either.

Always add value or ask for forgiveness. As the Battle Group Headquarters, it is your job to ask “so what?” during an incident. Your current intelligence desk should be working out why the enemy did what it did, what that means for the enemy scheme of manoeuvre, and what we can do to defeat them. You should be thinking about what the Battle Group is going to do about it. If you are unable to get supporting assets to the ground callsign, then you should be delivering orders for what that callsign needs to do in that situation. You are not in the fight and, if you position your headquarters in the right place, you are not getting shot at. You should be looking at the bigger picture for the ground callsign and offering guidance or assistance. If you need an asset and don’t already own it, then ask for it from brigade headquarters. If the CO is on the ground and issues orders, or relays an issue they‘re facing on the ground, then find solutions or options for them to choose from. It might not always be perfect, and it might mean redirecting assets from another task, but that is why the CO issues priorities and a main effort. Ultimately, when it all comes around to it, they trust you.

To wrap up. This is by no means an exhaustive list. Nor are these ideas new. Many of them were brought to my attention from others around me. I found that being an OPSO was more about talent managing some of the intelligent and motivated people around me than it was about doing the thinking by myself. These tips might or might not work for you and your team, but if you find at least one of these points to be useful, then it was worth putting pen to paper.