Background

Above the rank of Corporal, Warrant Officers and Senior Non-Commissioned Officers rarely have the legal authority of command to support their ability to achieve tasks. As such, Warrant Officers and Senior Non-Commissioned Officers may rely on the less tangible aspects of leadership to achieve their ends. They also influence commissioned officers and provide advice based on experience, support command decision making and oversee the execution of tasks. For soldiers, they are the face of military discipline and the custodians of the Army’s collective knowledge, customs and traditions.

The Warrant Officer and Non-Commissioned Officer Academy is the only unit in Army that delivers all-corps training for Australian Regular Army Warrant Officers and Non-Commissioned Officers as well as selected Army Reserve personnel. More specifically, Canungra Wing is dedicated to the preparation of all-corps Non-Commissioned Officers and Warrant Officers for promotion, providing training in command, leadership, management, operations and training. Consequently, the leadership skills, knowledge, attitudes and behaviours represented by our instructor body permeate through Army with each successful course the wing conducts.

Canungra Wing has a resident pool of 21 Warrant Officers and Sergeants, and is supported by an additional four Warrant Officer Class One from Training Support and Development Cell, and Warrant Officer and Non-Commissioned Officer Headquarters for the conduct of the Warrant Officer Advisors' Course and Regimental Sergeant Majors' Course. Each instructor was asked to reflect on their recent appointments and the leadership skills, knowledge attitudes and behaviours they used to achieve outcomes in to workplace.

The reflection asked each respondent to provide up to five positive and negative experiences, adopting an 'internalised' perspective. The responses were analysed to develop hypotheses on the nature of Warrant Officers and Senior Non-Commissioned Officer’s leadership and management and the impact this has on the delivery of all-corps training.

The Questionnaire

The questionnaire utilised the STAR format to capture the respondents' examples. The STAR format is a common interview response technique that allows respondents to provide concrete examples and is widely used by human resource and recruitment professionals.

The STAR format asked the respondents to provide the following:

Situation: Describe a challenge, problem or opportunity you were required to respond to.

Task: Outline what the task, outcome or end-state you were required to achieve for this situation.

Actions: Summarise what actions/steps you used to complete the task.

Result: Detail the outcome of the actions. Was this what was expected and how beneficial was it?

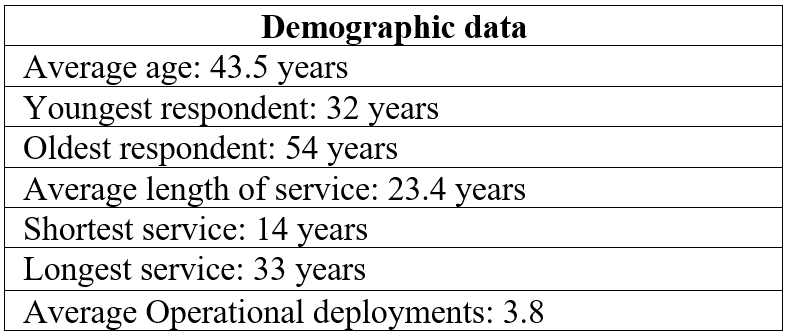

All data collected has been sanitised to ensure the anonymity of the respondents. The questionnaire utilised a number of demographic questions to assist in filtering the responses, as well as a range of rating fields for each participant to complete. Tables 1 – 3 detail the demographic data; Table 1 outlines the age and length of service, with the average age being 43.5 years old, the youngest was 32 years and the oldest was 54 years. The length of service ranged from 14 years to 33 years, with an average of 23.4 years of service. Every respondent had at least one operational deployment, with an average of 3.8 deployments.

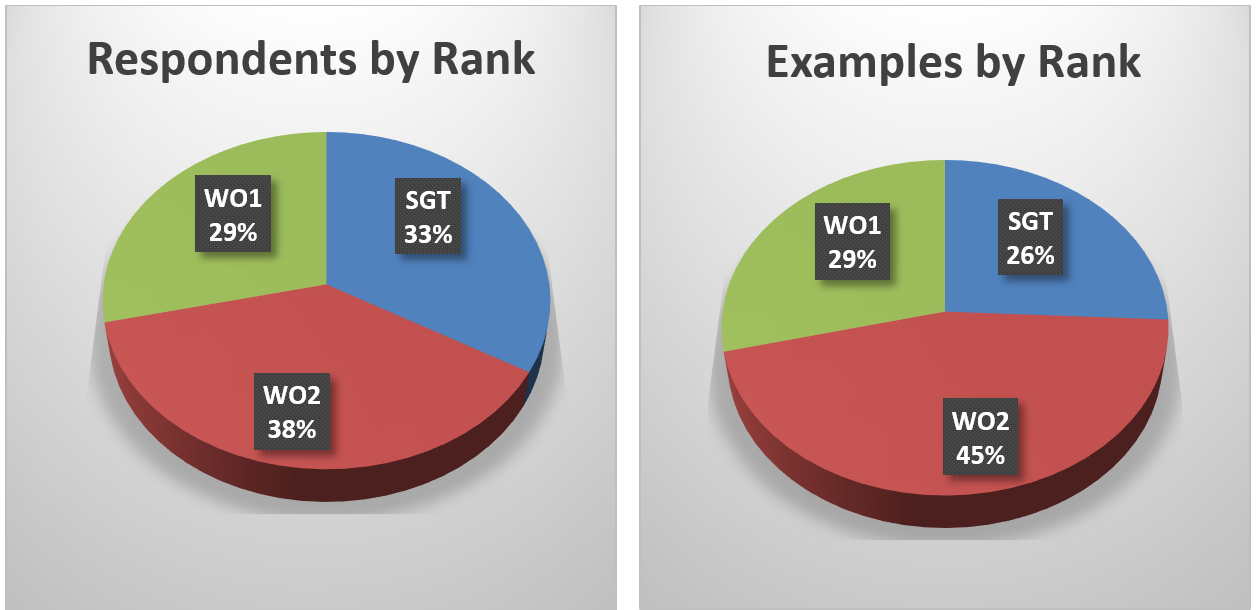

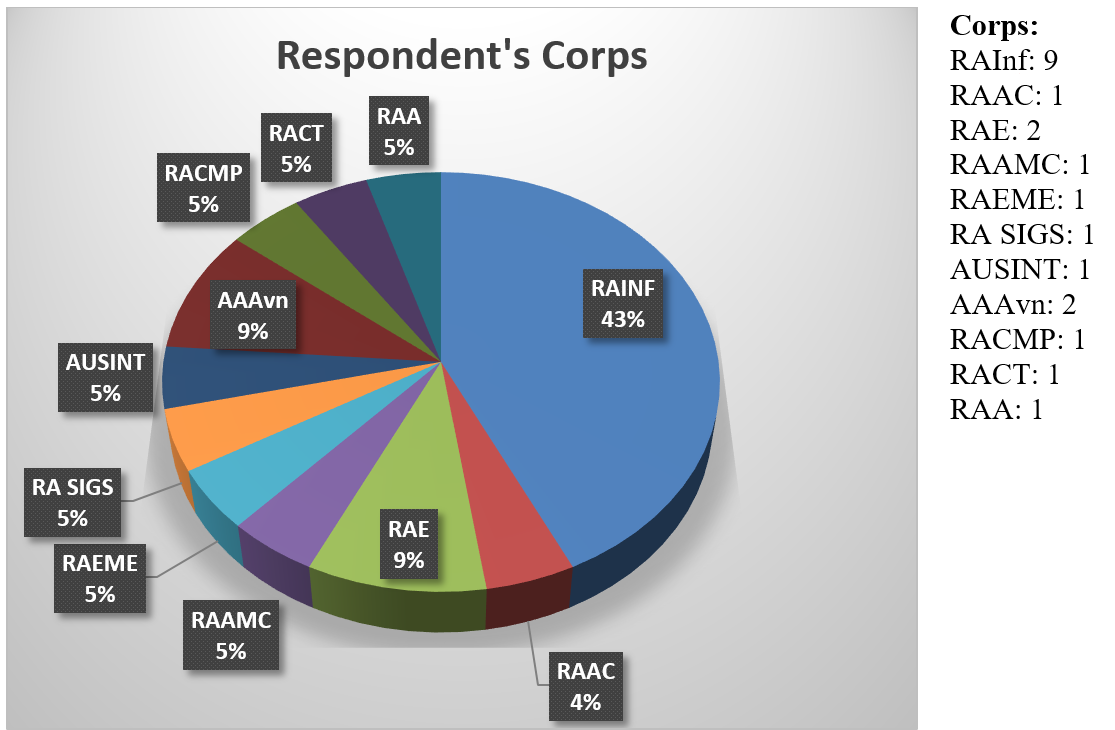

In total, the dataset gathered from twenty one Sergeants, Warrant Officers Class One and Warrant Officers Class Two was based on 66 examples. Table 2 shows the breakup of respondents by rank and compares it to the examples provided by rank, with Warrant Officers Class Two providing the largest percentage of examples. Table 3 shows the respondents by corps, with Royal Australian Infantry being the most represented.

The Results

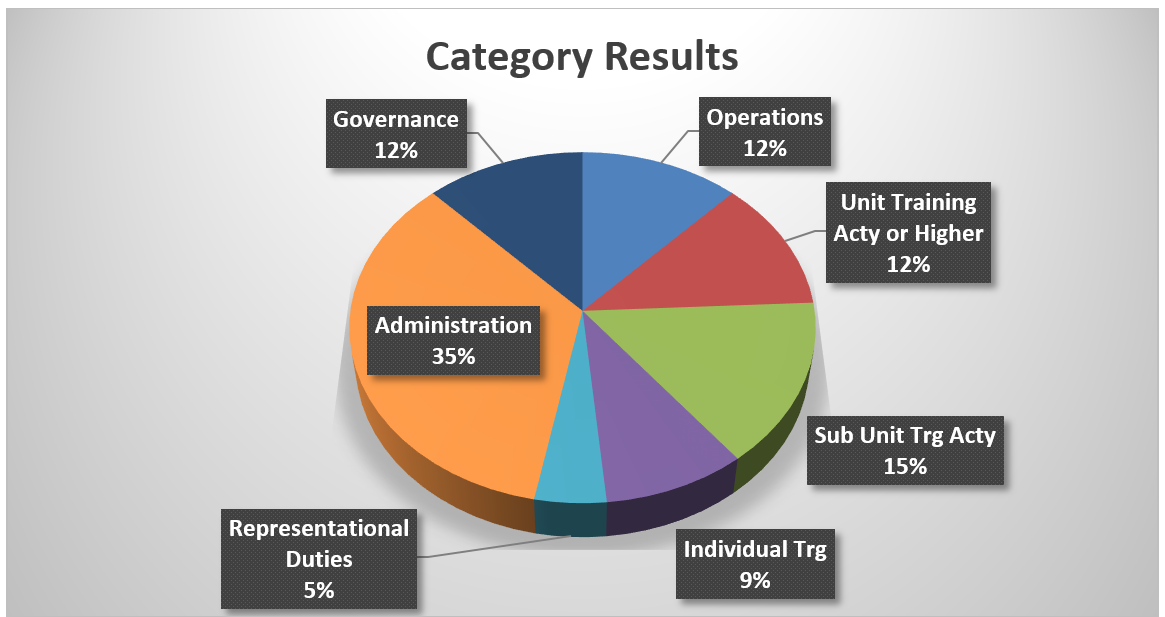

The results confirm that there is a greater perception that Warrant Officers and Senior Non-Commissioned Officers have a functional focus on management and leadership. Table 4 highlights that 79% of the examples were considered either a leadership or management orientated situation. Additionally the examples were centred on training (36%) and administration (35%), as outlined in Table 5.

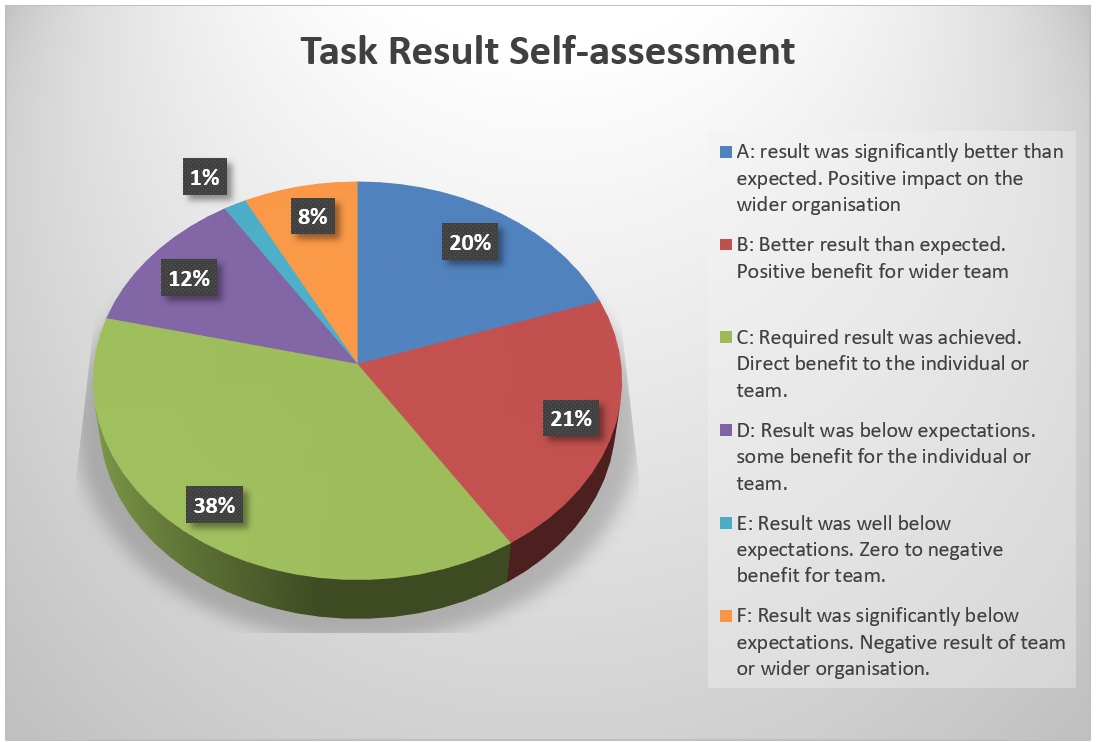

Table 6 shows the results based on the individual's self-assessment. The results/outcome from each example were largely positive in nature, with a distribution cluster around benefit to the individual (40%), then team and organisation combined (43%), with only 10 (18%) examples being negative.

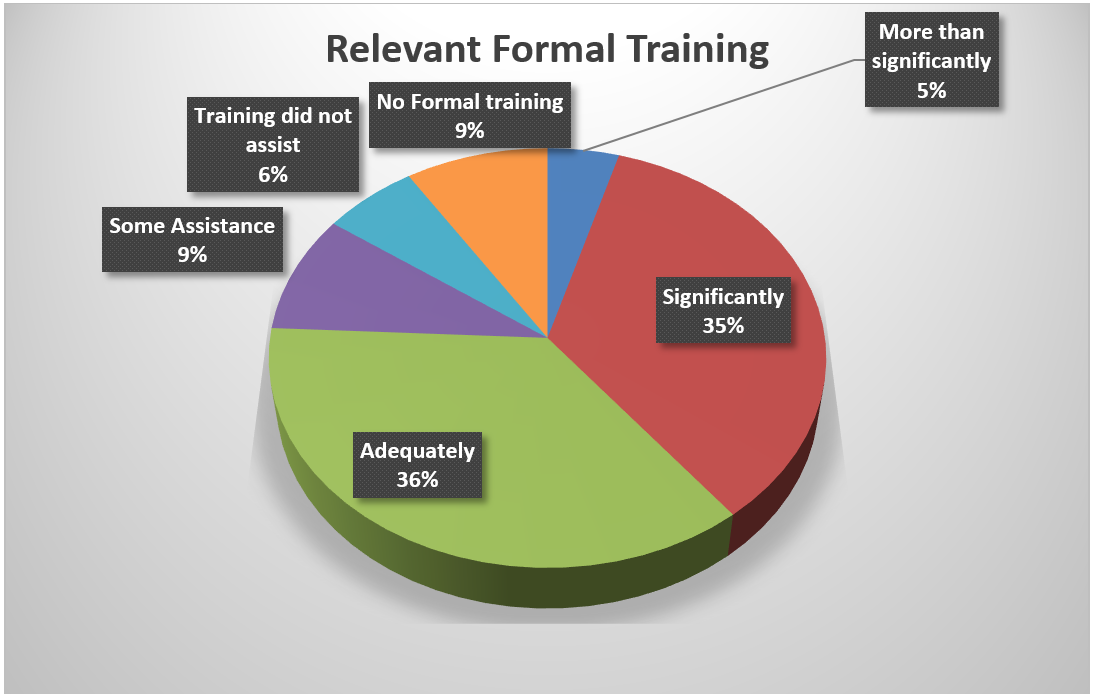

The respondents were asked to rate how the formal training they received assisted them in the examples. Overall, formal training was rated highly with 78% of respondents rating it between adequate to more than significant. Table 7 shows the breakdown of how the respondents rated the formal training.

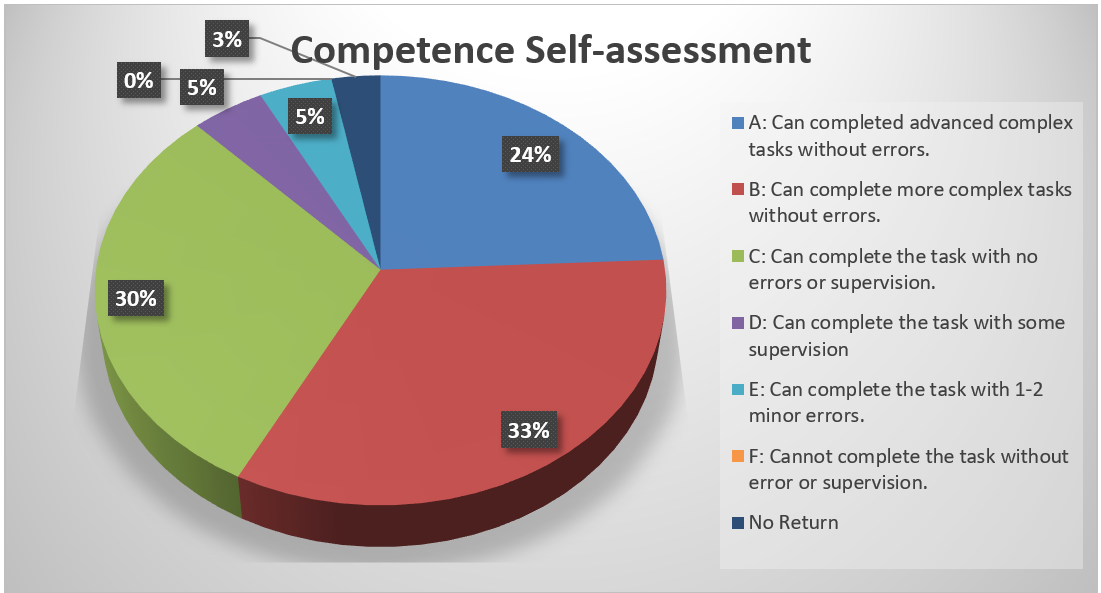

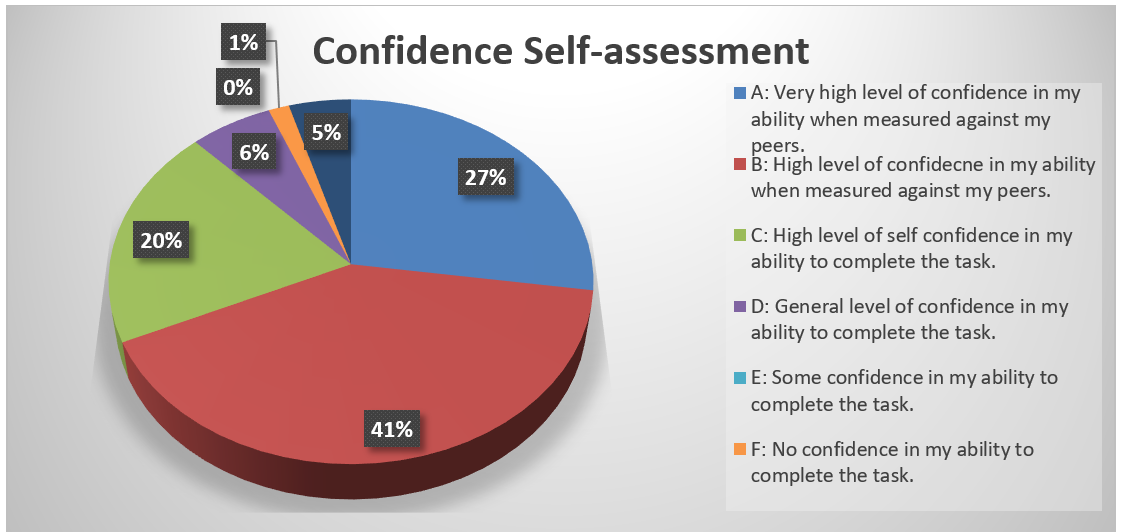

Tables 8 and 9 show the respondents' self-assessed competence and confidence in effectively resolving the example. Respondents self-assessed both elements very highly with 87% rating their ability to complete tasks without error and 88% having high or very high self confidence in their ability.

Limitation

A key limitation of the questionnaire is that it is self-reflective and not a 360° review of each example. A 360° review provides numerous perspectives from a range of people who were part of, or witness to, the incident. This enables the respondent's experience to be compared against the experiences of others and a weighting or value can be assigned based on the accuracy of the compared experiences. All examples are only from the viewpoint of the respondent and this has been taken into consideration when reviewing the results. As such, this paper does not seek to make categorical judgements, rather to generate hypotheses, thoughts and discussion.

Observations

The first observation is more of a confirmation of what is commonly known; that Warrant Officers and Senior Non-Commissioned Officers, who are rarely placed in positions with command authority, mainly deal with incidents relating to management and leadership. Given that the Australian Army mission statement is “to prepare land forces for war,” it is no surprise that the examples are centred on administration, including military justice, and training from individual to collective sub-unit. It is critically important that Warrant Officers and Senior Non-Commissioned Officers are effective and efficient at administrative and training management to ensure that the force is ready, trained and capable to achieve the commander’s intent. Without positional command authority, Warrant Officers and Senior Non-Commissioned Officers need to rely more on their leadership ability to create willing followership within the organisation. They need to be effective at not only leading their subordinates but also their peers and superiors through job competence and building strong working relationships. Many respondents stated that the formal training they received was adequate to more than sufficient to meet the needs of the example, which highlights the importance of the all-corps soldier training continuum.

The second observation gained from the data is that nearly all the examples had a positive self-assessment on the outcome and the respondent rated their competence and confidence highly. Given the number of respondents and the average length of service, it is improbable that the respondents have only had positives experiences throughout their career, yet they only shared positives examples. This is an interesting observation and not something that was expected when the questionnaire was designed. There are several perspectives that could be considered regarding this observation. This paper will focus on the reflective self-awareness and the willingness to share personal insights. These elements can be considered important attributes of a good instructor.

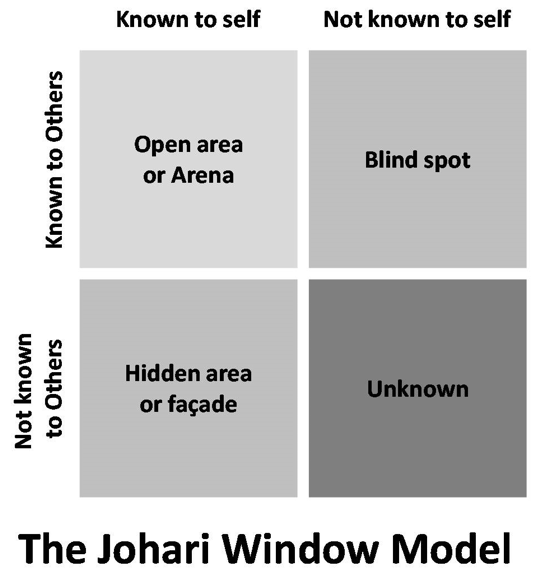

The Johari Window is a simple psychological tool developed by Joseph Luft and Harry Ingham in 1955, which can be useful in illustrating and improving self-awareness, as well as increasing mutual understanding between individuals and groups. As detailed in figure 1, the Johari Window is a 4 pane model that looks at what information is known by you and others (the open area or arena), what information you have not shared with others (the hidden area or facade), what information others have not shared with you (the blind spot) and what information in unknown to you and others (the unknown).

The size of each pane changes depending on the individual or group. A person will have a larger open pane for close family and friends but might have a smaller open pane with work colleagues. The size of the open pane largely comes down to the level of trust you have in the individual or group you are with and the level of trust the individual or group has in you. The more you trust the person the more you are willing to share, so you increase the open area and reduce the hidden area by telling people things about yourself. To reduce your blind spot you ask people to provide information about yourself. The more trust there is the more likely people are willing to openly share information about you. Telling and asking are key to increasing the open pane.

Reflective self-awareness is limiting when only looking at something from your own perspective; by asking others for feedback you increase the level of reflection and increases what can be learnt from the experience. Sharing this reflection allows others to gain a better understanding of yourself, but also provides a second loop of learning for the person or people who you have shared this information with. The Kolb Experiential Learning model that is explained in the LWD 7-6 Adventurous Training (Chapter 3) highlights that an experience alone is insufficient to ensure learning takes place. Reflection is essential to determine which of the methods employed to address the problem set worked best and those which should be abandoned as ineffective. It is important to note that getting things wrong is part of the learning cycle and it is better to get it wrong in a training environment rather than during operations.

The importance of sharing personal and historical experiences as part of the learning cycle was highlighted in Mission Critical Teams (Cline, 2017). Stories are 'used to collect, deposit, analyse, store, and disseminate information as instruments of socialization' (Chilisa, 2011, p. 138) 'In other words, as new Firefighters join the Fire Department-New York they are told stories of past fires to help them understand what that community values and what is expected of them in the future' (Cline, 2017 p 87). While the example used in this circumstance relates specifically to the Fire Department-New York, the lessons are easily adapted to the Army’s context. A narrative or story is an effective way to communicate lessons learnt from pervious learning evolutions or experiences, both in training and on operations. It is more likely that learners will become, and remain, engaged in the learning process when the instructor is effective at sharing personal or historical stories. Additionally, learners may also be more willing to share their own personal experiences.

Stories themselves are simply vehicles to facilitate learning. It is critical for the instructor to tie the story to the learning outcomes and facilitate the conversation to draw the lessons out. The Army is expected to operate in complex and chaotic environments where simply doing what you or someone else did last time may not guarantee success.

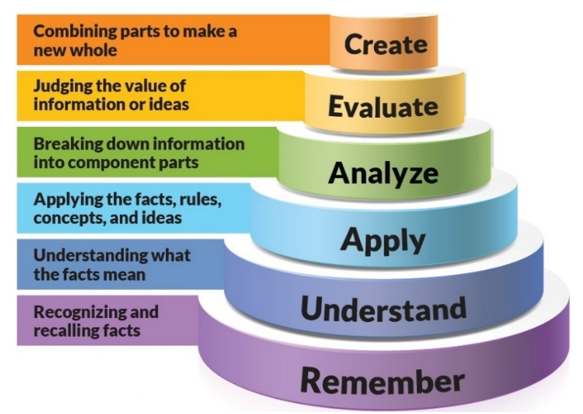

Contextualising the personal story to draw out the lessons enables the learner to apply higher learning principles to the story as explained in Bloom’s Taxonomy. The lower order learning principles of remember, understand and apply are more appropriate for technical problems where it is important to follow the process to guarantee an outcome. With analyse, evaluate and create, the focus shifts to considering the variables and how they may impact the outcome. Effectively linking storytelling and reflective self-awareness provides a sound learning framework to draw out lessons and provide context. Further information on Bloom’s Taxonomy can be found on the Australian Defence Electronic Learning Environment (Unclassified) as part of the Army Education Centre’s Instructor Professional Development course.

A further consideration is that sharing personal experiences, particularly of failure, can be both beneficial and risky. Trust is the key operating factor in every relationship and it is no different in the instructor / learner relationship. The instructor can use personal experiences to help build trust between them and the learner, but by only sharing negative personal stories there is the risk of the learner losing trust in the instructor because of perceived incompetence. It is important to balance positive and negative stories to build trust.

'Often, in poor-performing cultures, the virus that is infecting the organisation is low trust and the symptoms are wide-ranging dysfunction, redundancy, turnover, bureaucracy, disengagement, and fraud. It’s not that leaders aren’t smart or don’t care; they’re just focused on the wrong cause and they mistakenly underplay trust-building as 'soft' or secondary – when it should actually be the primary focus.' (Stephen Covey, 2016)

Establishing and building trust is an ongoing activity that takes time and effort to nurture. Instructors must be capable of quickly establishing the trust of the learner and maintaining the trust throughout the learning process. Instructors that are able to conduct reflective self-awareness on their interactions with the learner are able to adapt their actions and behaviours to effectively build trust. Covey (2006), The Speed of Trust, provides an interesting perspective on the benefits and costs inherent to a trust-based model.

It is important to note that the purpose of this discussion paper is not to conduct a deep dive into a range of concepts, frameworks and models but to provide material to generate a conversation on reflective self-awareness.

Conclusion

The survey of instructors within the Warrant Officer and Non-Commissioned Officer Academy and their experiences is important. It is these instructors that have been selected by the Directorate of Soldier Career Management-Army to lead, train and mentor Corporals, Sergeants and Warrant Officers Class Two as they prepare for promotion to the next rank. The attitudes and experiences of these instructors influence the quality and style of the training and education provided. The survey responses returned by the instructors were overwhelmingly positive. Johari’s Window may go some way to providing an explanation, however when overlayed with Preston Cline’s 2017 work on 'Mission Critical Teams' can extrapolate an interesting tension between the instructor and the learner as a result of this research. The Kolb experiential learning model, resident within Army’s adventurous training doctrine, may be an under-utilised framework for the development of reflective self-awareness and facilitation skills. Finally, Bloom’s Taxonomy, and its current diffusion through Army’s training system led by the Army Education Centre, may provide a useful framework to leverage the years of valuable service resident in Army’s instructors and enhance the training experience of the learner.

This paper and the research design was conceived by Captain Callum Waite and Major Matthew Grantham at Canungra Wing, Warrant Officer and Non-Commissioned Officer Academy.