As a company with a strong interest in training development and simulation integration, we were keen participants and delegates at the recent Australasian Simulation Congress 2017 where there was a large focus on the rise of simulators and simulated training options for Australia’s Defence Force (ADF). One of the key talking points throughout the congress from both uniformed and industry personnel centred on the requirement for Defence to begin taking an holistic approach in the integration of simulation technology to its training.

Over the past 13 years, both in uniform, and as part of a company who has embraced the use of simulation within training, we have developed a unique perspective and lessons learned on this mostly underutilised training method. During this time we have watched ADF simulation grow in physical size, quantity and, more significantly, quality. However, the introduction of these systems hasn’t necessarily seen the commensurate improvement in training efficiency, value and outcome. So, the question becomes, why?

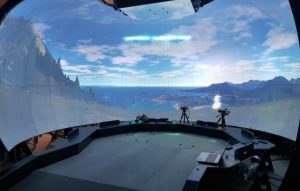

A key lesson is that technology in itself does not equate to capability, it is simply a tool. It’s how you implement that tool that makes it effective. Technology is fast encroaching on, and sometimes engulfing, the profession of arms and we are starting to see more and more simulators and emulators in the hands of our Defence Force members. From near perfect replications of aircraft cockpits wrapped in 270° projected screens, to closed network online courses in basic navigation, to advanced military tactics, almost anything is possible with the help of good multimedia tools and a software company. We have seen, both in industry and within Defence, examples of shiny, new, high-end pieces of kit that work, fill a need and can be a combat multiplier, simply left in the barracks, forward operating base (FOB) or storeroom when it comes time to deploy on exercise/operations or training. There can be many explanations as to why this may be the case: the natural human reluctance to, and fear of, change; generational gap between instructors and students exacerbated by digital vs analog technology; inadequate hands on training; equipment unsuitable for operational use; and laziness or unwillingness to learn new things.

However, in our experience, the most common influence as to why technology is discarded or dismissed, is the inability to adequately train and contextualise the technology within unit 'training, techniques and procedures' (TTP) and operational employment. If a soldier can’t see how he’ll use this in real time operations, why bother learning it? This is where the message is becoming lost. The temptation is to become focused on the technology rather than the capability, hindering both Defence and industry’s ability to fully exploit simulation systems. The resultant capability provided by the technology will only be generated through the implementation of tailored, designed, and most importantly, relevant training, provided by dedicated staff who fully understand both Defence requirements and the technology.

The common refrain (and with good reason) is that nothing can replace live training. This is a notion that, while undoubtedly true, has its flaws. There needs to be a shift in the mentality that simulation based training is a threat to live training. It is simply, training that is linked to competencies, proficiencies and realistic outcomes that exists to support and enhance live training. Picture you’re on an exercise, part of a company level assault on a tree-line, or adjusting indirect fires onto a particularly dangerous ghost gum in the Shoalwater Bay Training Area. How much realistic tactical appreciation are you actually conducting on the battlespace? While this has immense value training basic soldier skills and technical drills, how realistically are we assessing a commander’s decision-making cycles and their application to real time battle formations and capabilities in a proactive/reactive environment? Utilising in-depth scenarios and immersive training through simulation, in conjunction with live training to develop the decision makers' technical and tactical skillsets, needs to be the focus, allowing for the next step in training development. The willingness to have all training contextualized and immersive is critical to pushing and testing the boundaries of training delivery.

So how do we use simulation to better prepare our soldiers and maximise our resources once we are ready to ‘go live’?

In order to answer this question, we have identified two key areas that we believe are important to understand in order to move forward.

Firstly, simulation training requires dedicated staff to manage the capability. During the Australasian Simulation Congress, Director of Air Force Ranges, Darren Manser, noted that in working with a 'live, virtual and constructive' environment, he wanted “a persistent workforce of people who can develop scenarios, manage accreditation, and take care of modelling and the security of facilities" – that work force does not exist in the scale needed both now and in the future. Dedicated staff who can fully support and integrate the system into training continuums is essential to the effectiveness of that system. Simulation staff require in-depth knowledge of the equipment and software so there is a clear picture of exact capabilities and limitations that can be linked with training outcomes.

Colonel Spencer Norris, director of Army’s Capability Operations and Land Simulation, talked about the need to 'get industry to understand what our capability is'. This is a critical point. The effective integration of simulation in Defence training is a two-way street - Defence must understand the technology and Industry must understand the capability requirement. Only with that mutual understanding can we fully exploit existing and emerging opportunities. Simulation staff must understand how the system is to be used for multi levelled training and operational employment if they are to develop robust, relevant training scenarios and outcomes that integrate with the ADF’s holistic capabilities.

Secondly, there needs to be a cultural change within Defence on how to approach simulators and training. Staff not willing to fully embrace newer methods of training, whether they be via simulation, transferring from analog systems to digital or any other method, should not be developing and leading training. This mindset can be detrimental as it does not set the conditions for a modern, fast moving, digitized and continuously advancing ADF. Even with analog systems sometimes being kept in service as redundancy, illiteracy towards up-and-coming technology can only be seen as neglect towards the advancement of the ADF as a whole. This change in culture will take some time and involve losing some old habits, while also increasing the understanding of staff and students of what simulation can provide.

Training staff need to ‘think outside the box’ when it comes to designing, developing and implementing simulation training. All too often, simulated training is just a rehash of what has been done before, without any of the innovation that has made Australian service personnel so renowned around the world. By continuing to push technology, new and enhanced techniques can be developed to ensure that training is as relevant, targeted and efficient as possible.

We look forward to continued opportunities, such as the Australasian Simulation Congress, to continue the progress being made on the effectiveness of simulation technology. It is essential that Defence and industry continue working together alongside trainers in order to push the boundaries and enhance Defence’s capability. With a simulator’s ability to provide complex and immersive environments, while requiring significantly less resources, coupled with skilled and experienced trainers to produce realistic, targeted and relevant training outcomes, the conditions are set for optimising the training of future generations.