Introduction

The Chief of Army recently published his guidance, Army in Motion, which declares that the Australian Army will need to build a more agile and sustainable workforce through adopting Total Workforce initiatives. This will require the implementation of modern organisational work practices as well as finding ways to attract personnel with needed skills to fill current gaps and in emerging capability areas.[1] It acknowledges that Army needs to adapt to compete for, and retain, talent through changes in work organisation and demographics. To this end, it is prudent to understand some of the different military service models being utilised in other countries in order to identify opportunities and options.

Singapore recently introduced a new service model called the Singaporean Armed Forces Volunteer Corps (SAFVC). This model was designed to engage and provide a service option for sections of the population that previous had limited or no opportunity to provide part-time military service. This article will outline the context and features of the SAFVC and discuss opportunities for the Australian Army.

Context

Singapore, a sovereign nation state since 1965, has a population of approximately 5.6 million. This is comprised of approximately 3.5 million citizens and 0.5 million permanent residents, with the balance being non-permanent residents (including a large ex-patriot workforce). Notably, the proportion of females to males has been steadily increasing and now represents 1000 females to 959 males.[2]

The Singaporean Armed Forces (SAF) are based on a National Service system where all eligible male citizens serve full-time for 2 years (on completion of high school) then a further 10 years part-time. At the core of the SAF is a full-time cadre, known as the ‘Career Military Force’, that consists of 39,000 personnel that fill most of the senior ranks. This is augmented by about 47,000 personnel serving their 2 years full-time National Service duty. The ‘Main Force’ consists of a further 400,000 personnel serving part-time for 10 years after their National Service. They are subject to annual training cycles and routine training commitments.

The well-established Singaporean National Service model has, until recently, provided very limited options for individuals to serve in the Armed forces outside of the National Service framework. Females, new citizens and older citizens were effectively excluded from part-time military service. In 2013, the Government of Singapore initiated a review aimed at strengthening the National Service model. This review made a number of recommendations, including the formation of a Volunteer Corps designed to engage these previously underutilised portions of the population. Critically, the SAFVC was not introduced in isolation; it was part of a suite of other complimentary recommendations aimed at increasing the effectiveness of the National Service program such as expanding opportunities for National Servicemen with relevant civilian skills to contribute in their areas of expertise.[3]

A Volunteer Corps for the SAF

The SAFVC was established in 2015 with the dual aims of directly contributing to national defence and indirectly strengthening support for the National Service program. The new part-time military service option was open to women, first generation Permanent Residents and new citizens. It also has a higher age limit than the National Service program (45 years versus 40 years). The SAFVC is coordinated and administrated by a formation level SAFVC Headquarters. The SAFVC also functions as a Training Establishment for the SAFVC Basic Training.[4]

SAFVC Volunteers undertake an initial two weeks of Basic Training. This can be completed over a continuous period of ten weekdays or across a series of weekends and provides basic military skills and values. After Basic Training (usually in their second year of service) the Volunteers complete a two-week period of Qualification (trade) training in their allocated specialisation with some trades requiring an extra two weeks of Advanced training.[5] SAFVC Volunteers volunteer for 10 Active Volunteer Service Years (AVS) but can resign at any time with three months’ notice. SAFVC Volunteers are expected to serve for at least two weeks a year and will typically be called up for training / deployment three to six months prior to the commitment. Their civilian employment is protected in legislation in the same way as that for National Service duty.[6]

Volunteers can nominate from approximately 30 specialisations[7] including:

- Auxiliary Security Trooper

- Bridge Watchkeeper

- C4 (Command, Control, Communication and Computers) Expert

- InfoMedia Staff

- Army Infrastructure Inspector

- Dangerous Goods Expert

- Specialist professions such as doctors, lawyers and psychologists.[8]

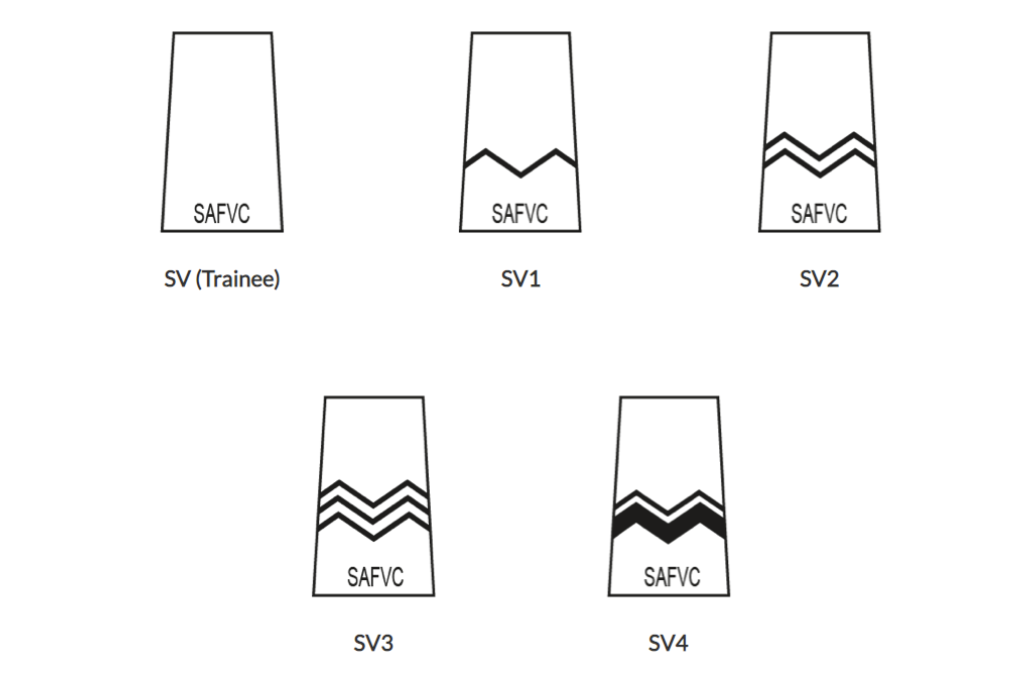

SAFVC Volunteers can choose to re-role in another specialisation at any time (if they meet role requirements) but need to undergo the required qualification and advanced training. There is also a SAFVC specific rank structure and insignia consisting of 5 levels (SAFVC Volunteer through to SAFVC Volunteer 4).

Compared to the relatively large National Service program the numbers in the SAFVC so far are very small: they currently number about 700 with 100-150 recruited per year.[9] However, the implementation of the SAFVC has not been without controversy. Some issues have been raised in the media, including security concerns regarding the loyalty of new citizens, the implications of the varying training levels when SAFVC Volunteers are operating alongside National Service members, and how much capability the SAFVC will actually contribute given its relatively low numbers.[10] Whilst there is supportive media around the deployment of SAFVC Volunteers there is little published information to date on any frictions associated with their employment and integration with the Career Military Force and National Servicemen.

At first glance, establishing a new administrative structure, service category and rank structure for such a small force seems like a lot of effort for few, relatively insignificant, capability outcomes. However, the Singapore Government has created a part-time military service option for a whole range of its population that was previously excluded. This approach has not compromised the current National Service structure and provided a potentially fast and scalable means to draw valuable skills and talent from a broader national talent pool.

Opportunities for the Australian Army

The Chief of Army, via his 2019 Commander’s Intent and Army in Motion, has challenged the organisation to look for opportunities across a range of areas into order to ensure the force is Ready Now and Future Ready. One of the challenges is making the most of the talent available in the population... 'Army must focus employment principles to meet demographic and societal change. This includes building an agile and sustainable workforce through embracing Total Workforce models, implementing contemporary practices and identifying what skills Army’s future workforce needs and how these should be organised and distributed.' [11]

The Army Reserve is one means to reach deeper into the Australian population to explore and procure emerging capabilities and skills. However, the current predominant service offering is based on a traditional service model of entry level recruitment and ‘recruit to retirement’ generalist careers. Recruits must submit to lengthy periods of initial and trade training before earning basic qualifications. Military trades and the Army Reserve organisational structures are largely traditional and bear more similarities than differences to those at the turn of the century.[12] The Army Reserve is becoming increasingly metropolitan-centric and most 2nd Division units operate on a Tuesday night and Weekend training model. The Force Generation Cycle commitments in the 2nd Division are delivering a more combat ready force but are increasing training requirements and putting pressure on individual availability and development needs. These demands are taxing the part-time workforce and potentially affecting retention of individuals as their civilian work and family circumstances change. The Specialist Service Officer (SSO) avenue offers an alternate path but is limited to a few traditional professional areas in the commissioned ranks only.

Some demographics that could perhaps be better targeted with a different service offering include rural based populations, students, the underemployed in the service industry, young parents balancing their career, corporate leaders or under-represented (in the army workforce) ethic groups. Army in Motion confirms that new skills will be required in the future force.[13] The Army Reserve could be a flexible means to capture and nurture talent to develop emerging capabilities. Future oriented skill targets could include data scientists, UAV operators, marketers, and artificial intelligence engineers. An Other Ranks scheme, equivalent to that which SSOs are employed under, could include ‘in demand’ trades where there is a strong correlation between civilian skills and military employment, such as carpenters, plumbers, diesel mechanics, armourers, plant operators and linguists.

To drive engagement with a wider talent pool, the current ADF service processes would require more flexibility but, based on some earlier attempts, it is noted this may prove challenging. Those challenges notwithstanding, increased flexibility could include things such as shorter recruit and trade training, recruiting into trades or roles that do not have an equivalent in the current forces structure, creating more dynamic team structures, and/or setting different medical/fitness requirements. However, organisational suspicions to changing the current workforce paradigms are often strong, as indicated by the fate of previous programs that have not been sustained, such as the Reserve Response Force, High Readiness Reserves and the Ready Reserve. The Singaporeans appear to have subverted at least some of this obstacle by creating a new organisation that can operate without some of the constraints of the current framework yet still be a part of the Total Force.

Whilst not a declared outcome of the Singaporean program, it provides a means to rapidly put civilians into uniform with a baseline of sufficient military training in order to: meet specific operational or organisational needs; acquire expertise to develop emerging capabilities; or test innovative ideas. It is also a means for targeting specific demographics by shaping a task that suits availability, skills and preferences while contributing a capability outcome.

It is important to note that none of these concepts integrated into the SAFVC are completely novel for the Australian Army and a number of these ideas have been proposed in the past or exist in some way already (such as the arrangements for the new cyber workforce, Regional Force Surveillance Units (RFSU), the SSO scheme and the volunteer officers of the Australian Cadet Corps). Each of these programs is celebrated individually but the wider potential and lessons they offer seem lost in the pervasive organisational paradigms.

Conclusion

The SAFVC provides a useful example of an alternative workforce model for voluntary, part-time military service. It was introduced to reinforce the existing national service structure and provide an opportunity for previously ineligible people to serve part-time in the military forces. It has widened the potential recruiting pool and enabled more rapid procurement of priority skill sets for military employment. It features aspects such as short training/qualifications times, specialist (rather than generalist) focus, a specific rank structure, annual duty requirements that are known well in advance, a base of two-week training blocks and a dedicated Headquarters / training centre. The SAFVC implementation has been declared a success by the Singapore Government but it is still small and there are concerns such as the about integration of SAFVC Volunteers and National Service on deployment given different training levels and possible security risks regarding new citizens.

The Australian Army has been challenged to embrace different pathways to generate capability and to change its approach to the workforce in ways that better align with contemporary demographics and civilian employment demands. The Army Reserve is well placed to be at the forefront of this change. The traditional service offerings have been effective in the past but are not necessarily the complete solution for future demands. Paradigms such as Tuesday night and weekend training, lengthy residential recruit and qualification courses, generalist orientation, and significant training requirements in the Force Generation Cycle have produced a more combat ready Army Reserve but may have limited the recruiting pool and denied the Australian Army skills it needs for specialist areas and emerging capabilities.

The SAFVC offers the Australian Army some potentially valuable lessons on the establishment of a new service offering designed to engage a previously underutilised portion of the population. Many of the features are not unfamiliar to the Australian Army. However, the opportunity now exists to find the means to revitalise recruitment and improve engagement with under-utilised portions of the Australian population base in order to help meet the strategic challenge to become an Army that is ‘Future Ready’.

Perhaps an Australian version could be called the Citizen Military Force? There is plenty of historical material on how a force dedicated to a limited task, such as local defence of its home areas, could be organised and trained.