This article was published in Smart Soldier 67, February 2022.

It is no secret that as a soldier, you are cumulatively exposed to higher degrees of physiological and psychological stress through your career compared with more conventional employment roles. The compounding effect of this stress can have serious and detrimental long-term impacts on your health and well-being. This is a broad and complex topic; however, the aim of this article is to focus on physical stress at an individual level. In simple terms, that is exercise. Understanding the effects of exercise on the body’s capacity assists in injury prevention through effective training load management.

What is training load?

Training load is ‘the amount of physical work done by an individual’. Training load can be often referred to as stress (physical) but for the purpose of this article it will be called ‘training load’ or simply ‘load’. Apply the correct doses of training load or stimulus, as will be discussed later, and the body gets stronger or fitter depending on the stimulus. The result is a physiological adaptation which is evident as an increased capacity, perhaps more endurance, greater strength, or increased power depending on what was applied. If the stimulus or activity levels are insufficient, your body will decrease in capacity which will result in a reduction of strength or fitness capacity.

Too much training load without equal consideration of your body’s capacity to recover means you are at a greater risk of being injured. What needs to be given careful consideration is that training load and its effect on the body’s structures are inclusive of everything you did in the day. The range of load on the body can vary from sedentary office work, maintaining equipment and stores, high intensity physical training through to mission-specific rehearsals such as section attacks and patrolling. All these things contribute to the total application of physical load on your body through a given period. Every tissue in the body – whether bone, muscles, tendons or ligaments – is living tissue and has a certain capacity to cope with load and recover. If a load is applied that is much greater than a tissue’s capacity (ability to recover and adapt), then the risk of injury is increased. Generally speaking, skeletal muscle presents with soreness more commonly but recovers quickly. Conversely, connective tissue and bone may not be symptomatically sore, but recover much slower than skeletal muscle and may not have recovered between high load events. This often results in overuse injuries that may present weeks after the initial stimulus of excessive load without adequate recovery.

What is training load management?

Load management is the practice of controlling training loads in order to reduce the risk of injury and enhance performance. In athletic terminology, the practice of load management is called periodisation. In this setting, the management of load is simplified by having specified peak performance periods or competitions with designated recovery periods and consistent application of load. This load management plan would generally consist of high volume of training load initially but very low intensity in order to establish baseline capacity and reduce injury risk. The volume of training would be reduced as the intensity is increased moving towards specific performance and the competition, with each change being preceded by a recovery period. In military terms, the scope of employment often sees operational and capability training impact on the application of physical training loads, leading to an inconsistent approach to load management. This is difficult to forecast but not impossible when we look at the total load as inclusive of everything we do in the workplace.

What is adaptation?

Adaptation is the process your body goes through when reacting to load. This can also be known as the stress/recovery/adaptation cycle. When the body is exposed to a stimulus or event (eg. PT session), load is placed on the body. If the load applied is sufficiently high enough or different to what the body is accustomed, the body is essentially shocked and in order to protect itself it responds in a myriad of physiological ways, potentially becoming fitter or stronger in preparation for the next event or stimulus. Conversely, if the training load has insufficient intensity or is not different to what the body is already accustomed, then the stimulus will not be adequate enough to result in any significant adaptation and no increases in capacity will occur. The most important part of the equation is the recovery. After the load is applied, time and resources are needed to repair cell damage and restore the body. Many factors affect how efficient your body is at recovering, with the key ones being sleep, diet and stress (psychological). During deep sleep the body rejuvenates itself. When in high periods of training, adults should aim to sleep at least 7 – 9 hours per night. The body relies on sufficient and quality macro and micro nutrients in our diet to enable the repair and recovery of damaged tissue. If we are mentally stressed, the brain will assess that we are under physical threat and divert the body’s resources into being ready to cope with a threat, which diverts resources away from recovery. The key takeaway is that adaptation to load occurs during the recovery phase - not in the gym or on the track - and as a result of sufficient load which stimulates the body to protect itself by becoming stronger, fitter or better.

Real world example – what not to do!

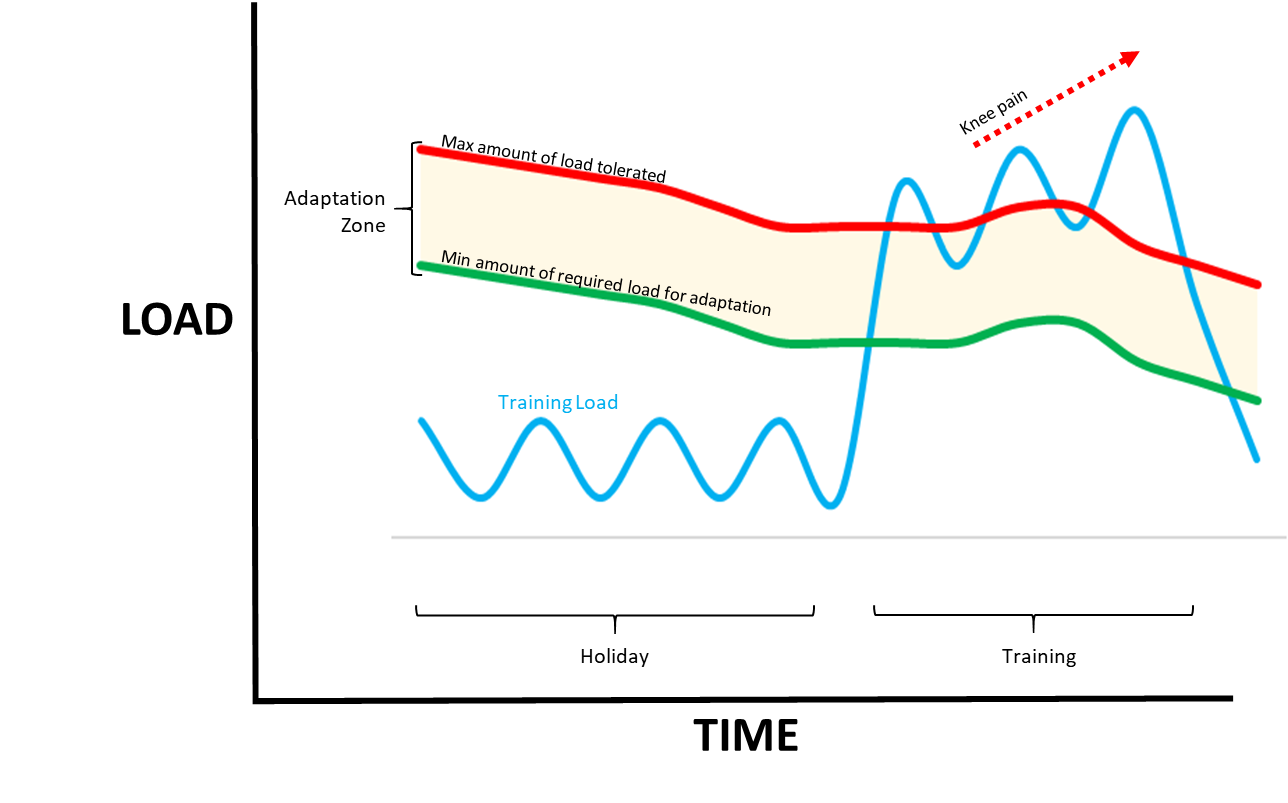

PTE Smith returns to work after Christmas leave and decides to get back into running after a month of travelling around Europe (obviously pre-COVID) which involved a bit too much partying and little in the way of exercise. He has gained a bit of excess weight and feels rather guilty about it, so he decides he will get back into running and going to the gym every day, doing the same thing he was doing before his holiday. The first week he feels very sore from training but isn’t worried because as they say, no pain no gain! After a week he starts to feel a bit better overall so pushes himself even more and is training every day. His knee has started to ache a bit when he starts running but it goes away after a while, so he still isn’t worried about it. This slowly gets worse over the following week, but he is able to push through the pain when running as he is on a roll with his training and doesn’t want to lose the gains he has made. Then one morning, he gets out of bed and can barely walk due to the pain in his knee and has to stop training completely.

This is a common example of how an overuse injury can occur when going from a period of little to no physical activity to a period of high amounts of physical activity. This can occur over a reasonably short period of time or over many weeks or months. The load PTE Smith was putting his body through greatly exceeded his body’s capacity (maximum amount of load tolerated) and his knee happened to be the weakest link.

Notice that while he is on holiday his capacity is decreasing, as he is applying very little stress to the body. When he gets back, he starts training every day just like he was before his holiday. But now that his capacity has decreased, he is exceeding it with the same training he was doing a month earlier. He may initially increase his capacity a bit, but without giving his body sufficient rest it starts decreasing while his training load continues to increase until he has to completely stop training due to injury.

Real world example – what to do!

What PTE Smith should have done is slowly progress his training, starting at 2-4 sessions a week and gradually increasing difficulty a little each week. Difficulty can be how hard you train (intensity – speed, weight, heart rate) or how long you train (volume – time, distance). When increasing difficulty, as a general rule, you should increase one parameter at a time (eg. each week you may increase the time you run by a few minutes, but don’t increase the time and speed in one go).

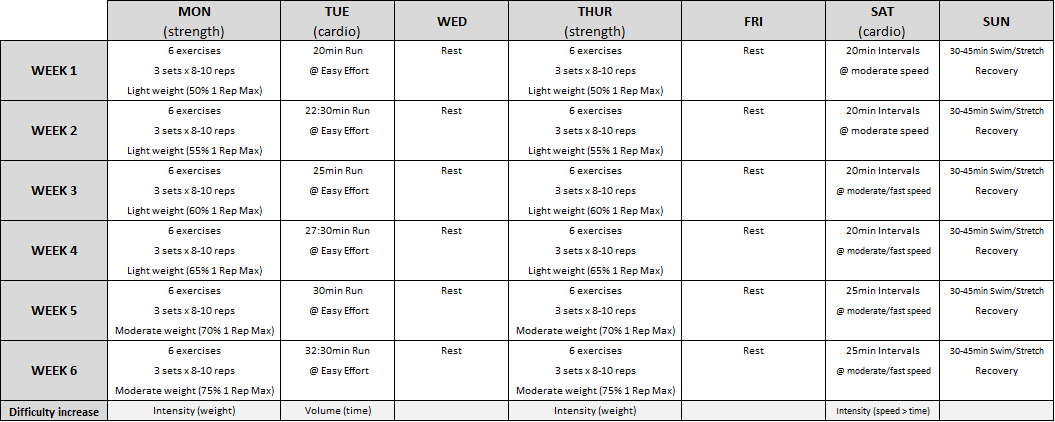

Below is a generic training program demonstrating a slow and steady progression in difficulty over a 6-week period.

*1RM = The hypothetical maximum weight you could lift for one repetition for a given exercise (Bench Press, Deadlift etc.)

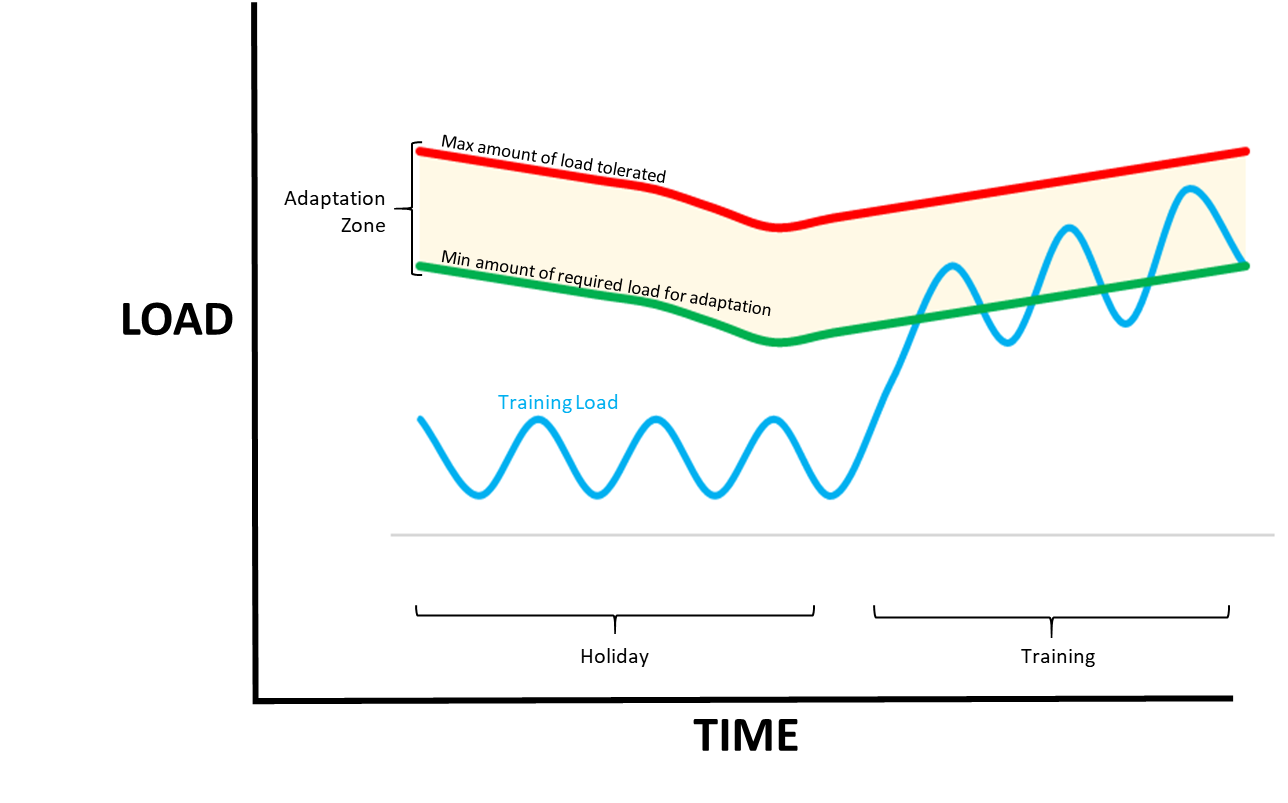

If PTE Smith followed a program like this, it is much less likely he would have developed his knee injury. Let’s take a look at what the same load/capacity graph would look like if he had followed the above program.

In the next diagram you see that he hits that adaptation zone (also known as the Goldilocks zone – not too much, not too little) with the right amount of load while allowing himself enough recovery between sessions. In theory this seems straightforward, but in reality it can be a bit more difficult. It requires the discipline to consistently stick to a training program that gradually builds difficulty over time (principle of progressive overload), allows for appropriate rest and is at a level that suits your ability and goals.

One other big point to remember is things like high stress, illness, poor nutrition and poor sleep will lower your capacity. This is why it is important to listen to your body. If these factors change for the worst (they will – life happens!) then the smart decision would be to ease back on your training a bit and focus on improving those things.

Who is most at risk?

Everyone is at risk of injury if they do too much too quickly, but there are two types of people who are more likely to get injured.

The first, like PTE Smith, is someone who has had a long period of time without consistent exercise and then gets a shot of motivation and gets back into exercise too quickly (the inconsistent exerciser). The other type is someone who trains very consistently and hard without giving themselves enough recovery and rest (the over-trainer).

For the first type, it is a matter of building up slowly and not getting straight back into the same training you were doing “six months ago before you deployed” and having that discipline to hold back a bit early on. For the second type, it is remembering that more isn’t always better - you can and will reach a point of diminishing return from a performance perspective. You may get away with training like this for a while, especially when you’re younger, but it will most likely catch up with you eventually in the form of chronic wear and tear injuries. It can be hard to realise this at the time, but don’t wait until it is too late.

Where to from here?

First thing is to have a look at your current training program/exercise regime and see if you fit into the category of the inconsistent exerciser or the over trainer, and from there implement minor changes.

|

The inconsistent exerciser: If your goal is to get back into exercise, then plan it out. It doesn’t have to be anything complex. If you struggle with discipline and motivation, ensure you do physical activities that you actually enjoy doing. When it comes to planning or tracking your workouts, just write down what you did last week then write down what you want to do this week. Ensure you include roughly how long and hard a workout was and make sure you make it just a little bit harder for the coming week, following the rules of increasing difficulty as already mentioned. For a more in-depth look at returning to training after time off see the following article: https://complete-physio.co.uk/returning-to-gym-after-lockdown-tips/ |

|

The over-trainer: Some of the common signs of overtraining are:

If you tick some of these boxes, it would be worthwhile getting in touch with a PTI or someone with experience and knowledge in strength and conditioning to review your training program. If you are specialising in a certain sport/training modality, try to find someone with specific knowledge in that area. For a more in-depth look at overtraining see the following article: |

Not just 'physical training'

What is not well considered by soldiers is that it isn’t just PT that places load and stress on the body – all activities that are physical in nature contribute to cumulative load placed on the body. Over the period of a day (or weeks in some instances) we need to be aware that high activity days where we have potentially walked additional distances wearing external loads such as body armour, conducted lift and carry activities such as loading or unloading vehicles or conducted high intensity tactical training scenarios all contribute to load. What can tend to happen is that people can overlook the workplace activities and continue with scheduled training regardless of what took place in the workplace over the preceding days. This small oversight can be just enough to create an overtraining scenario leading towards the onset of an overuse injury or stress reaction. It’s important that we listen to the body and consider what we have done throughout each day. Any increases in training load of greater than per cent across a period have the potential to result in a training injury. So if you have scheduled to run a long endurance session but the preceding day at work covered a significant amount of steps at the range wearing body armour, you need to adjust your scheduled training to complement the rest of your activities in order to avoid the potential of overuse injuries.

In considering all training load we also need to consider the progression of training post injury, where an all too common example sees individuals have an extended time away from normal duties in order to rehabilitate an injury, then as soon as they are officially “rehabilitated” they are returned to work on normal duties which may see them sent straight out on exercise with little to no build up training. In instances where their role is relatively sedentary then it is probably quite low risk. However, if you are in a combat role conducting physically arduous tasks over a period of time, you are at a greater risk of getting a new injury or exacerbating the one you just had.

In short…

Be physically active, regularly. Be patient, be disciplined and play the long game. Focus on getting the basics right. Enjoy training, make it fun when you can. Get stronger, get fitter, but work smarter not necessarily harder. When it is hard though, ensure you give your body the rest and recovery it needs. A good rule to follow in the longer term is to rest at least one day a week and one week every three months. Find a knowledgeable person to assist you with designing a training program specific to your body and your goals.

Do all this and understand and practice smart training load management and you can build your physical capacity and become a more resilient and injury free human being and soldier.