This article is part one of what I hope will be a series of articles about the soldier combat system. In this first article I examine the concept of the soldier as a system. Assuming I don’t receive too much abuse in the comments section or from my peers at work, a second article will talk about the vital topic of integration and a third article will discuss the system life cycle and adaptive acquisition. These articles are aimed at the warfighter community: and as much as possible, I will avoid complex technical language and provide examples of how these concepts will benefit the close combatant.

The 'Christmas Tree' Effect

Every soldier has been there. Another piece of equipment emerges from the Q store and it’s up to you to carry it. More ammunition, pyrotechnics, night fighting equipment, radios, batteries, electronic counter measures or any of seemingly hundreds of different items that are deemed essential to the mission. Of course, you also need to carry your primary weapon, water, rations, wet weather and sleeping gear. In most situations combat body armour and helmet must also be worn. Having loaded up with all this equipment, you are expected to 'seek out and close with the enemy, to kill or capture him, to seize and hold ground and to repel attack by day or night, regardless of season, weather or terrain.'

When this happens our soldiers are treated like a 'Christmas Tree'. More and more equipment is hung off them without adequate thought as to how that equipment integrates with other equipment that is already carried. This approach may not adequately consider the flow on effects of all this weight carriage. The adverse effect of load carriage on soldiers includes reduced tactical mobility and increased chance of both acute and chronic injuries. A better approach is to think of the soldier as a system.

What is the Soldier Combat System?

There are many definitions of a system, one of the simpler but still authoritative definitions is: 'A system is a construct or collection of different elements that together produce results not obtainable by the elements alone.'[1] Systems are made up of sub-systems which are in turn made up of components. Each of these sub-systems and components are optimised towards achieving the mission of the system as a whole and each sub-system must integrate with the other elements that are part of the system.

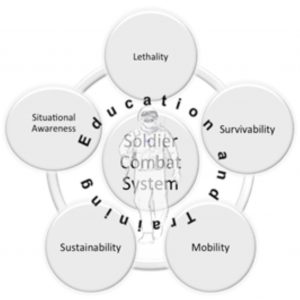

The Soldier Combat System is all the elements that together allow an individual soldier to have an effect on the battlefield. It is the equipment used by a soldier to apply lethal or non-lethal effects, communicate and gain situational awareness, survive, sustain, move and operate within the close combat environment. These elements must integrate together and they must also integrate with the human being who forms the core of the Soldier Combat System. In this way the equipment is part of a system, not an aggregation of individual components. The individual pieces of equipment must also be designed to optimise the achievement of the mission.

The sub-systems of the Soldier Combat System

Optimising the System, not the Sub-system

Let’s have a look at two example sub-systems designed to achieve survivability. This will demonstrate the difference between an optimised sub-system and an optimised system. Consider the Modular Combat Body Armour System (MCBAS) that was introduced in to service in 2008. The purpose of MCBAS was to provide protection to the soldier wearing it. MCBAS was designed to optimise the level of protection. It provided 'the highest level of protection we could afford to give our people and what was technically available at that time[2].' It weighed 12-16 kg depending on the configuration, and as a result it dramatically reduced mobility, agility and decreased endurance. Australian soldiers wearing MCBAS could not keep up with the Afghan soldiers they were mentoring[3]. MCBAS was an optimised sub-system, but did not allow for optimisation of the Soldier Combat System as a whole.

Contrast this approach with the Tiered Body Armour System (TBAS), which was designed, not as an optimal sub-system for providing protection, but as a piece of equipment that would optimise the operation of the Soldier Combat System as a whole. TBAS weighs 6-8 kg less than MCBAS. The coverage offered by the soft armour inserts in TBAS is less than in MCBAS, however this is balanced by increased mobility, agility and endurance. Put simply, a soldier in TBAS has slightly less physical armour coverage, but is more able to move and seek cover on the battlefield. Essentially TBAS is designed not as an optimised sub-system, but to optimise the performance of the Soldier Combat System as a whole.

Trade Offs and The Effects Of Additional Weight

The design of the Soldier Combat System is one where trade offs are constantly considered. A trade off is a decision made to balance two desirable but competing priorities. A common trade off decision that must be made with the Soldier Combat System is adding capability at the expense of additional weight. Anyone who has carried a dismounted combatant’s load instinctively knows that more weight is a bad thing, but can we quantify what the effects are?

Defence Scientist and Technology (DST) Group have studied the issue of weight burden in depth. They have concluded that load carriage has adverse outcomes for a soldier’s health as well as reduced mobility, lethality and survivability. Specifically, their report states that “Weight load, march duration, load distribution, terrain and individual fitness levels together with load carriage equipment design contribute to the incidence of acute load carriage injuries.[4]” In addition, the cumulative effect of heavy load carriage is a likely contributor to chronic injuries such as stress fractures.

On the subject of battlefield mobility, the DST Group report concluded that every additional 1 kg a soldier has to carry, correlates to a 1-1.5% decrease in soldier performance when conducting agility and mobility tests. They have also found load carriage causes a decrease in marksmanship and survivability. The decrease in marksmanship could be due to an inability to stabilise the weapon due to muscle fatigue. A greater concern is altered cognitive functioning. Carrying extra weight results in less vigilance, situational awareness and decision making ability[5].

This data presents system designers, along with combat commanders, complex considerations for optimising the Soldier Combat System and avoiding the 'Christmas Tree' effect. Issuing extra equipment such as a more advanced optic sight adds to capability and increases lethality. But if the advanced optic sight is heavy, it may actually decrease overall lethality: the result being the soldier experiences a net decrease in capability.

There is no easy answer to these problems. In part, the problem is owned by the capability manager who has responsibility for the design of the Soldier Combat System. However, it is the combat commander who will ultimately decide a soldier’s posture based on threat and risk tolerance in a given environment. Ultimately it is commanders who own the risk for their subordinates and their decision will be based on many inputs; but it is worth noting that they can be informed by academic studies that have quantified performance effects of TBAS and examined the trade-off between passive protection (body armour coverage and ballistic rating) and active protection (soldier mobility)[6].

User Feedback

So where do we go from here? The input of soldiers who use the equipment is vitally important to capability managers. If you have feedback or an idea about how soldiers are equipped you have two options: you can complain to your mates and it’s likely that nothing will change, or you can speak to organisations that have the ability to influence the Soldier Combat Ensemble. Diggerworks is an organisation whose mission is to identify, develop and integrate Soldier Combat System solutions to continuously enhance the capability of the ADF Land Combatant. If you have feedback you can engage with Diggerworks to help ensure the gear you are issued is as good as it can be. The Diggerworks team regularly visits ADF units or you can contact Diggerworks directly by emailing them diggerworks [at] defence.gov.au (subject: User%20Inquiry) (here).

If you have a good idea you can also submit to 'Brigade Good Ideas' expos. If you don’t believe a piece of equipment you have been issued is performing satisfactorily, submit a RODUM: a guide on how to do this is included in Smart Soldier Issue 47. Providing this user feedback will greatly increase the chance that you and your soldiers will continue to be equipped with the best possible gear and you aren’t treated like a 'Christmas Tree'.

Next article, we will look at integration of sub systems within the Soldier Combat System and with other systems that form a combined arms team.

One factor that I think has changed the game since my time is that today we (society) seem so much more adverse to combat casualties. Possibly this is the ongoing effect of the myth of DESERT STORM when in clean precise surgical war no one (on the good guy side) gets hurt because we have such a technological edge. The reality is, or course, radically different but the public perception remains that we have to do everything possible to reduce casualties and that includes providing more and better equipment for the soldier to carry...maybe a case of the whole being less than the sum of its parts...

My point is that, if we want a more effective lighter and more mobile soldier, we may have to accept risk in other areas like probability of casualties...even starship troopers get hurt and killed...

P.S Thank you for TBAS whomever signed off on it.