Training programs associated with strength, conditioning and maximal power are being recognised as important components of military fitness. Historically military fitness has had a significant focus on aerobic endurance style activities. This may be due to the simplicity of implementing training programs, periodisation, or a follow on from the ‘base’ military style adaptation needed at Kapooka.

As a training outcome, the current tests associated with physical training programs revolve around biannual or annual assessments and are not necessarily specifically tailored or designed to meet the intent of the ever evolving, high-end war fighting requirements. 'There is no doubt that a war fighter's maximal strength and power will dictate the magnitude of force and power in submaximal high intensity endurance performances, literally translating into better performance on the modern day battle field.' (William J. Kraemer and Tunde Szivak, 2012).

Discussion

Although professional sport and soldiering are two different disciplines there is a correlation between specific training outcomes. Traditionally, muscular endurance training programs have used moderate loads lifted for 12-15 repetitions. 'Any form of training must mirror the specific demands of the sport or intent. In resistance training, this means that the load used should match the resistance that must be overcome while competing. The number of repetitions or the duration of exercise bouts in a session should approach that during the event. Muscular endurance training makes up only one part of an annual strength program – even for endurance athletes. It should follow a phase of maximal strength training because the greater their potential for strength endurance, the more force they will be able to apply over a prolonged period. Heavy strength training has also been shown to improve exercise economy in endurance athletes.' (Bompa TO. 1999).

In the modern soldiering environment, a soldier performs up to five sessions a week dictated by operational tempo. This is exclusive of any training that the individual soldier may do in his or her own time. Why is this relevant…? A professional sporting organisation generally will train five days per week with multiple sessions that revolve around recovery, recuperation and rest with a weekly focal point (Game Day). A soldier may train 1-5 days per week with a focal point of a deployment, exercise, return from injury or to just be a functional, athletic soldier capable of anything, anytime. The difference is that we train our soldiers without the support of nutrition, massage, recovery sessions, and pre, during and post workout supplementation.

Digiarnie / Lance Hohaia running into the Papua New Guinea defence while representing New Zealand during the 2008 Rugby League World Cup. Group A match NZ versus PNG on 01-11-2008 at Skilled Park, Gold Coast, Australia.

The intent of being physically fit, mentally resilient and emotionally intelligent to win a game, battle or war suggests that the correlation between high-end war fighting and elite athletes is more familiar than we recognise.

During an eight week period in early 2017, 8/9 RAR conducted a specifically designed high performance program that revolved around increasing strength and power as Phase 1. The intent is that Phase 1 will lead into a 12 week program (Phase 2). 8/9 RAR provided 26 candidates to conduct Phase 1 of the strength/power program.

The 8/9 RAR command team were interested in conducting a specifically designed elite sports program that had tailored military goals associated with high-end war fighting to see if a correlation could be made. The program itself revolved around six compound movements: back squat, floor press, high pull, push press, snatch grip deadlift and dumbbell lunge. It also included a battle beep test which was specifically designed to test the association between strength, power, agility and coordination under fatigue while utilising fine motor skills such as a magazine change.

In the work The Psychological Effects of Combat as cited in (Grossman and Siddle, 1999) the following information is relevant to the battle beep test:

- 60-80 BPM normal resting heart rate

- 115 BPM fine motor skills begin to deteriorate

- 115-145 BPM optimal complex motor skills, visual reaction time, cognitive reaction time

- 145 BPM complex motor skills deteriorate

- 175 BPM cognitive processing deteriorates, loss of peripheral visual, loss of depth perception, loss of near vision and auditory exclusion

- 175+ BPM irrational fighting or fleeing, freezing, submissive behavior

The battle beep test focused on controlling the candidate’s heart rate whilst developing the compound movements associated with strength/power relevant to the job specificity of conducting a short burst, taking a firing position and conducting a magazine change under test, time and progressively fatiguing conditions.

The results

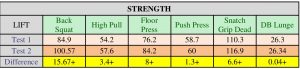

The individual strength movement and average strength gains can also be seen in fig 1.

Figure 1

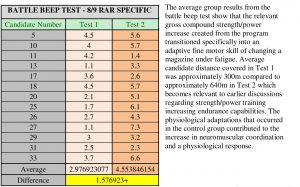

The strength/power training that was incorporated into the program was based on six primary compound lifts with supplementary power and intensity movements (as seen in fig 1). The major increase in strength occurred over the lower body plane. This suggests that current training programs in Defence focus too much on upper body strength compared to using the biggest, most powerful muscles - the legs. The training results suggest that this increase in lower body strength and power had a second order effect in the job specific battle beep test. By increasing the output of the legs, the candidates were able to lunge, power up, and move explosively and dynamically across the 7m shuttle. The increase in strength allowed for the candidate to conduct more repetitions comfortably prior to lactic acid building up or a spike in heart rate and deterioration on fine motor skills. The individual and specific battle beep test average can be seen in fig 2. Situations such as a magazine drop, not making the beep line or a weapon malfunction was recorded as a stop.

Figure 2

During the last eight weeks, 8/9 RAR have been involved in a study based around an elite sports high performance strength/power training program with a specific focus on military correlation. Although this study is in its early stages, and the data is raw, we are seeing positive results without injury.

Time, money, effort and resources are continually put into the development of high-end war fighting with a focus on gaining an adaptive edge. Put simply, it comes back to the artistic development of soldiers physically, mentally, emotionally and spiritually. Whilst science plays a role, it is the art of how we tailor a system and a program to meet the enduring developmental needs of the solider and the warfighting force element. A holistic approach is essential if we are to promote a resilient and adaptive force. A sound strength and conditioning model that is structured and contains periodisation shaped towards key performance metrics and fluidity will ensure our soldiers train to optimise performance.

Way ahead

Phase 2. The 12 week program will branch into adaptive cardiovascular response, prehabilitation, weight load walks (specific to the infantry PESA) and collation of subjective data such as energy levels. A further data analysis will be conducted at the completion of the study. This will provide the opportunity to affirm and validate the outputs of Phase 1 whilst informing the development of a sustainable training and development model for soldiers and force elements within combat teams, battle groups and combat brigades. That said, this model can be tailored for any ‘group set’ of soldiers and ECNs in order to optimise their performance relative to their strength and output requirements.

Just one example that I can directly relate to this - I deployed to Kabul as a part of a UASUV Drive Team. I wasnt originally panelled in for that position, however I ended up replacing someone partly because eventhough they were a CFL and were considered incredibly fit, they werent physically STRONG enough to pull the Team Commander (our heaviest person) out of the car with all their gear and weapons on during basic drills an I could - repeatedly. Was it all upper body strength? No! All lower body in my personal experience, so I'm not suprised by the data you listed. Look at the standardised PT session and its a no brainer that its not setup to help in scenarios like I just mentioned. And if you consider the warfare we are engaged in now, those scenarios are highly likely to continue in the coming years and thats a very basic drill without adding catastrophic circumstances into it.

Me being able to pull a 100kg+ soldier with all their gear on out of a 4WD in a scenario where their body is completely limp and lifeless can literally only be attributed to my own strength training outside of PT. Sure this other soldier was super fit, but was their fitness functional for the job they needed to do? No.

I think what you're dping is fantastic and I sincerely hope it continues to produce quality data eventually resulting in its implementation Army wide. Having been posted to 2CDO yourself, I'm sure you will remember seeing members conduct more decentralised PT. Perhaps conducting some more studies/research in that area in regards to how and why they train and utilise recovery methods the way they do would further benefit/ and improve your argument for this study. I wish you all the success, please keep us updated.

Glad to see someone utilising factual data backed by qualified results and thinking outside the box .... congrats

Excllent piece of work. Your holistic approach with sound scientific principles is a credit to you. I loved your article on how you balanced both maximum output with endurance in a periodised model. Couldn't agree more. Looks like you worked hard and also your team to do the work. Well done to you and the team. The soldiers must have been impressed by following some scientific training principles how quickly they progressed. Great program mate.

As opposed to my other comment I made elsewhere....sorry for being so conclusive and naive as I failed to appreciate the balance of your overall methodology. Once I reread your article properly I personally now think you have nailed it. Quite Brilliant I reckon....

Cheers. MD

Browny

The question of military PT and it's effectiveness seems to have gone through a number of evolutions over time but in the end it should come down to the end state. As the author rightly points out, they train for warfare and to achieve success in circumstances of high stress, high fatigue and high stakes...focussing training on passing an annual fitness test does not appear to enable successful outcomes in that primary role! An all encompassing training approach towards developing performance to enable mental/physical resilience when it is needed and developing a mental blue print or pool for soldiers to draw on is crucial. We are a product of our past experiences.

Keep up the good work!