Warning. This article discusses mental health issues, including suicide, which may be triggering for some. If this article elicits a response, please contact your nearest Mental Health professional or resources such as Life Line and Beyond Blue.

“Look after your soldiers and your career will look after itself” – Anonymous

I first came across the above quote as a young lieutenant in the Corps & Advanced Training Wing of the Defence Force School of Signals during my Regimental Officers Basic Course. It has sat with me as a founding ideology for my leadership style and has served me greatly. Whilst I will continue to embody that ideal into the future, there comes a point where one must ask themselves "but at what cost?".

I live and breathe a servant leadership style that, for me, typifies what military leadership is, or should be, about. But it can be hugely taxing if you don't know how to manage your own personal self-care. Despite discussing the importance of self-care in a previous article I wrote, my failings manifested in a severe mental and emotional breakdown.

For context, I'm a father of two school age boys; married for over a decade to an incredible woman who is a long serving and highly capable Army Warrant Officer. To date, I have served over 20 years in the Australian Defence Force (ADF), with stints as a Maritime Warfare officer, and for the last 12 years a Royal Australian Corps of Signals officer. From a career perspective, I've spent the last decade in high tempo (read: extremely busy), high stress roles both domestically and internationally, like much of the ADF. The impact of these roles has led me to some pretty dark and turbulent places, which I'll now highlight.

Picture this: it's 7am, I've just dropped my boys at before school care, grabbed some coffee beans from the local cafe 100m up the road and started walking back to my car. As I do, some work-related thoughts enter my mind and I'm instantly and (somewhat unexpectedly) triggered. My heart starts racing, my breathing shortens and intensifies. Then, I feel emotions rising so quickly that I race for my car to avoid public judgement/embarrassment. Once I get into the driver's seat, I immediately lose control. Tears stream down my face, I struggle for air, I can't focus or ground myself and all I want is for these feelings to stop. For over 20 minutes, I sat shaking, sobbing and stranded in my car that morning before calming myself enough to get home, where I was catatonic for the rest of the day.

Though the above example is certainly not the worst I've experienced, those feelings, and that panic/anxiety attack, are an all too common occurrence for me these days. For the last 12 months I've been dealing with the aftermath of significant burnout stemming from the past decade of pushing myself too hard, for too long, and with little to no regard for my own mental health or self-care. It's the all too common "I didn't think it would happen to me", or thinking I knew better. I've spent more than 20 years in the military, traversed war zones, seen the devastation nature can cause, and was capable of managing significant workloads and dealing with numerous conflicting priorities. I saw myself as a resilient person and that I knew my limits. I was wrong.

For those unsure "Burnout", in an occupational context, is defined by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as "a syndrome conceptualised as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed". It may seem like a new concept, something the workforce is pushing in a post-Covid world, but burnout has been a psychosocial risk for some time now. Most of us probably know or have heard of it as "hustle culture": long-term exhaustion to achieve productivity, or doing things like wearing busyness, high levels of fatigue, and long working hours as badges of honour. In an attempt to constantly improve and move forward as an individual, for my team(s) and for the enterprise, I did those things myself. As you've just read, it eventually came at a huge cost. One that almost included my life as I came extremely close on multiple occasions, to committing the act of suicide. *If this has caused any concern, or your own feelings / thoughts of self-harm, please reach out to your nearest Mental Health professional or call Lifeline on 13 11 14.

Burnout within a professional context can stem from a few sources. I would posit most people, including myself, are familiar with the burnout resulting from significant mental and emotional fatigue i.e. "Overload". There are at least another two primary sources known as "Under Challenge" and "Neglect". Burnout from "Under Challenge" is the literal opposite of the "Overload" subtype, where you lack stimulation, leading to a demise in motivation. "Neglect" on the other hand relates to a lack of direction, purpose, guidance, or structure in your work. While my experiences relate almost entirely to "overload", I have been exposed to and heard of the other subtypes throughout my career.

Given the varied sources, it might be hard to rationalise how burnout presents. In my experience, the resultant feeling of (overload) burnout is hard to describe. It's being so tired that you have to think to breathe. That your every day is essentially an out of body experience; you're a passenger in your own life. You get to a point where you're pushing so hard that whilst the workload seems insurmountable, you strive to get it done, regardless the cost. Taking time for oneself seems irrelevant when you are in this mindset, though. I promise you, I took time off when I felt I could. This included Long Service Leave, stints of recreational leave (up to 2 months at a time), and other extended breaks. The thing with burnout is that it creeps up on you. You're like a frog in slow boiling water, unaware that you are cooking from the inside (due to the build-up of stress and other emotions) until it's too late. Then, BAM! It hits you like a freight train. If the leave, or rest, you are taking is not actually restorative, your metaphorical cup isn't filled, and you continue to drain an already empty container. Depending on the type and/or cause of burnout and an individual's resilience levels, this manifestation could take months or even years which can greatly exacerbate the symptoms and other effects.

As indicated earlier, my battle with burnout and the associated mental health conditions took more than a decade to develop. Others may be longer or shorter and their associated symptoms and conditions may also differ. For me, the catalyst was my wife highlighting my moods, temperament, and most importantly – that the way I was interacting with her and our children had severely degraded. After this turning point, it still took another six months before I sought professional help through ‘Open Arms’. The point being, everyone's path will look different and it's important to be compassionate towards yourself (something I still struggle with) by taking each day as it comes.

What can we do as individuals?

As mentioned, my experiences are largely from "overload", but I have also observed that Defence (certainly from my respective Navy and Army careers) also suffers significantly from "neglect". Though "under challenge" may be present, it's not something I've come across regularly enough to consider it more deeply or as a significant enough risk. The point I'm making by highlighting my own observations is that we need to understand the threat and how it comes about, and how it impacts us before we can start to tackle it. Briefs on mental health have been a part of ADF annual training for at least the past decade, Defence also introduced annual mental health awareness days, and multiple supportive courses, but are they enough?

As individuals we all understand education is critically important when increasing knowledge on a specific topic. This remains true for mental health, and in this instance, burnout. The Havard Business Review article I referenced earlier is but one of many resources which could help. There is access to mental health professionals, your GP, other assets such as "The Burnout Project" Community (which has a free burnout calculator), and books such as "Burnout: Breaking the Stress Cycle" by Emily and Amelia Nagoski. Spend time reflecting on your own self-care and what you can do to support yourself and others. These resources also provide additional links for self-care.

What can we do as leaders?

Again, education. Not only for yourself, but your teams as well. Understand, evaluate, and analyse how tasks and objectives are approached, what risks they present, and what their level of priority actually is. To support my teams in the past, I have enforced the following policy: unless it is operationally urgent, the CO (or respective command) requires it, or we are behind on a deadline (that we don't control); it can wait until tomorrow.

Trust me when I say I know this is easier said than done, but – as leaders – it is essential that we truly know what the limitations of ourselves and our teams are. If we don't take care of them, we will have no one left to lead. Conversely, if we don't look after ourselves and lead by example, we will fail in our leadership roles to build more capable leaders in the future, thus causing our own demise through attrition from those failures. This reinforces the point above regarding self-care and making time to reflect on where you are at both physically and mentally.

For some leaders, their desire to progress will be at odds with what, on the surface, may appear to be less productivity. De-scoping a discussion on toxic traits, I refer back to the opening quote "look after your soldiers and your career will look after itself". Without their teams (or followers), leaders have no purpose. Therefore, it is imperative we do not sacrifice them to meet our own (potentially egotistical) goals. Servant leadership is a great tool for this as it is founded on humility, servitude, and putting the needs of the team before yourself (somewhat closely aligned with the Defence value of "Service").

To this end, push back on non-essential tasks and think of the human at the end of the stick when planning exercises and activities – what do they (or you) have left to give? It may cause grief in the short-term, but the resultant cultural benefits will outlive that pain. Conversely, if there is a cultural stigma towards saying "no", there are leadership responsibilities to challenge and change that stance. Whilst I understand there is risk, accepting said risk is your duty as a leader, as is enabling your team to effectively and efficiently achieve their objectives. If they are burnt out before they start the fight, they may as well stay at home.

*I use the term "leader(s)" as a collective term for supervisors, managers and those with leadership roles whether they are in a position of command/authority or not.

What can we do collectively?

Share your experiences! Be vulnerable! There is still a massive stigma around mental health in Defence – even in the wake of the Royal Commission into Defence and Veteran Suicide. I felt and observed it when I started this process. But throughout my journey, I've made a deliberate point to be as open as I can on my experiences in the hope it breaks down walls and encourages others to either seek help or share their own stories. If I only help one person, that's goal achieved. The more we can break this cycle, the better.

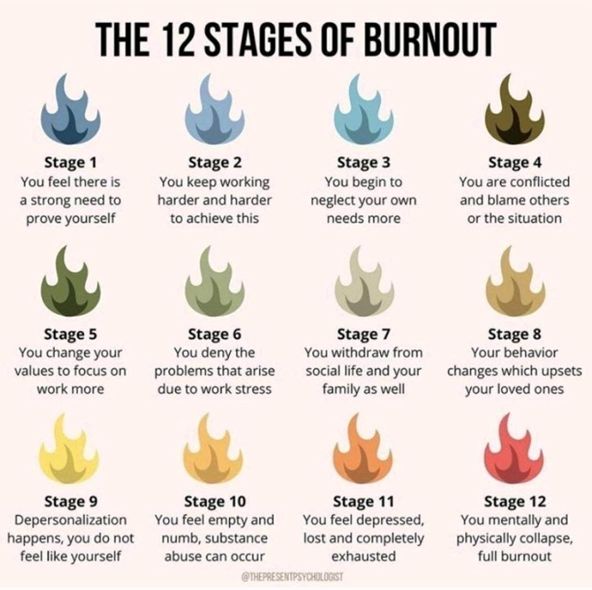

I implore you to take the time to review, research, and understand the signs and symptoms before you or a friend/colleague get caught out. In terms of signs and symptoms they are characterised in three dimensions: 1) feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion; 2) increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job; and 3) a sense of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment.” The below image depicts the stages of burnout and overarching feelings / symptoms. It’s important to note that this is one expert’s view, but it is something I found useful in understanding where I stood.

Image 1. The 12 Stages of Burnout

In addition to the calculator by the Burnout Community, Harvard Business Review published an article providing a "Two-Minute Burnout Check-up". While not comprehensive, both the calculator and article provide a starting point for everyone to make changes to their own work-life balance or to potentially seek external support. The latter is especially important to assist or mitigate the associated mental health conditions that stem from burnout such as depression and anxiety.

I hope the above sheds some light on what burnout is, how it can affect us, and what we can all do to help bulldoze the barriers to this and associated mental health conditions. For myself, I've made positive steps towards recovery in what will be a very long road, but it doesn't have to be like this for everyone. For context, I'm currently in recovery from at least 12 months in 'Stage 12' but spent the previous 4 years between 8-11 without recognising the signs. Notwithstanding my own journey, through honesty, vulnerability, and education – I'm hopeful we can all break the stigma.

If this article speaks to you in any way, please reach out to your local mental health support service like Beyond Blue or Open Arms, GP, friend(s), family, and/or supervisors.

*The views expressed in this article are my own based on lived experiences and observations. If I have caused angst in any way, I apologise but ask that you reflect upon 'why' as there may be some underlying challenges that need addressing.