2021 Cove Competition – 2nd Place

I am a 51-year-old woman who joined the Army as a challenge in my mid-20s. It was 1997. My only options as a female soldier were to join intelligence, transport, or signals. I was an accomplished journalist, having returned from photographing the Atlanta Olympics in 1996. I was up for something totally different and chose to be a radio operator. My story isn’t dissimilar to many others, particularly those who join the Reserve force – I have met doctors who join as infantrymen and scientists who sign up to drive trucks. The diversity of our people has always amazed me.

I rose to the rank of Lance Corporal as a Reserve soldier before commissioning as a public affairs officer, while professionally I moved into academia. I observed that parallels between military and the academic world are understated. Both are hierarchical and highly structured. Both have a history of gender inequity in senior roles, and both are – at heart – learning institutions with deep respect for knowledge and reflection. Senior rank in both requires an acquisition of knowledge and experience that is hard to achieve or replace, born of time in rank and exposure to diverse experiences.

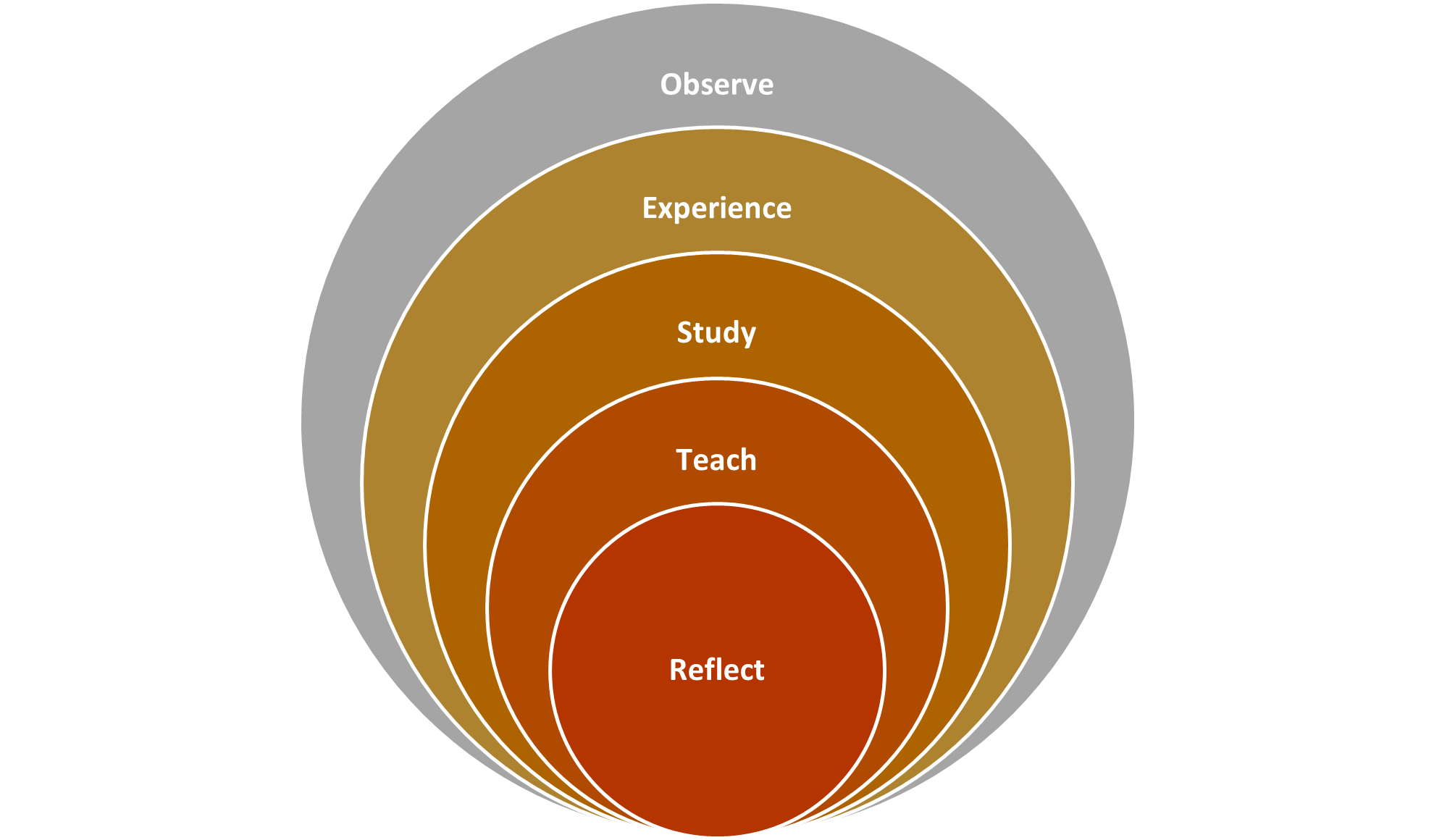

Australia has 43 universities. Army has three divisions. I was repeatedly reminded through experience that it’s competitive to get to the top of any level. As I matured, I learned to take a ‘marathon’ view – be prepared, be competent, build and sustain relationships, pick battles carefully, engage in critical self-reflection without succumbing to imposter syndrome, learn how to have hard conversations, and keep perspective. I created my own leadership development model [Fig 1] as I learned to lead through a repeat cycle of observation, experience, study, and teaching – with reflection embedded at each stage.

Image 01 / Personal Leadership Development Model, developed by the Author.

After decades of service, I’m now a Lieutenant Colonel, and a Professor of communication and education in my academic role where I study, teach, and lead innovation and curriculum design teams working in a conservative and unstable sector environment. Technically, I am at ceiling rank in both professions. I have settled on having no specific career ambitions; rather, I aim to enjoy what I do – create and be open to opportunity, and build others up so that I can step aside knowing that my legacy may be their success. This position – being comfortable to run your own race when you’re surrounded by highly competent peers or offered exciting opportunities – didn’t come easily. It was influenced by three key themes I have embraced: balance, congruence, and competence.

Balance: The higher you get in any position, the greater the perspective. Some people focus on the risk of falling from height and narrow in on their stance or view. They hold to and compete heavily for positions (including their role). This can be alienating and promote toxic and competitive behaviour. Balanced leaders are listeners and engage with competing positions. They realise that taking time to build a solid base rather than climb a single ladder will help foster stronger relationships and better judgement. I watched talented peers who climbed ladders quickly fall off early. I learned patience, sought skills and knowledge, built deep and genuine networks, and reflected on experience such as family trauma to help me keep perspective.

Congruence: Single-track experience develops expertise in one thing. While this may result in faster acceleration to leadership positions, those who live life across multiple tracks are able to apply knowledge and skills across diverse roles. You may take longer to climb, but when you do, you’ll be better at balance (see above). In addition to being an academic, manager, and military officer; I’m also a student of educational neuroscience, a mother of teenagers, and a trainer of young horses. I’m applying my knowledge of the brain (the neuroscience), horse training (the need to listen and ask ‘what’s going on?’ at every interaction) and raising independent children (where I apply skills from both other areas every day). I use listening and patience skills gained from horse training in my workplace daily, based on the simple premise: how do I help you feel heard? Great leaders often have multiple domains in which they operate – coach of the local footy team, member of a charity group, student, and parent as examples. By exposing ourselves to diverse experiences we can critically reflect on all areas to identify and apply connections.

Competence: Leaders take many forms, but as an applied linguist by academic trade, I have observed and learned from what I refer to as ‘peacock’ versus ‘brush turkey’ interactions. The ‘peacock’ likes to be seen, and reacts to other peacocks. The beautiful tails go up across a board table. Peacocks talk at one another, listening only for opportunity to display expertise, real or otherwise. The ‘brush turkey’ isn’t pretty, focussing on the job at hand. They don’t get distracted. Anyone who has tried to win a war with a brush turkey will know that you won’t win, in a ‘give up the garden until next spring’ type of way. Brush turkey leaders are strong in their resolve, which drives them to listen and support teams; their focus is on the outcome, not the moment. Early in my career, I used to try to be a peacock, attempting to get noticed and heard. I failed a lot. It took 19 years to become a Lieutenant Colonel, and 24 years to get to Professor. I became the brush turkey. I realised that good leaders notice when you’re competent, are kind to others, and do good work. They respect that you claim your space but don’t make being noticed your modus operandi. They understand and seek opportunities for congruence and maintain balance. I sought to become that leader.

My learning leadership cycle is currently in an observe phase again. What’s next? Who knows. I’ll reflect on that as it happens.

Robyn xx