The roles and responsibilities of a general duties medical officer (GDMO) in the Australian Army present a unique set of challenges. From commencing uniformed service as a general practice (GP) registrar, to attaining fellowship and progressing to more senior roles, there is an expectation that is not often placed upon civilian counterparts in a similar phase of their training continuum. The majority of the role in the deployed environment is bread and butter primary healthcare complaints, which understandably explains the choice of training college for GDMOs as The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP). However, with the doctrinal health effect of a Role 1 treatment team being able to provide damage control resuscitation, there is an expectation that the individual GDMO in charge of the treatment team is able to coordinate, facilitate, and lead this resuscitation – a function which is not necessarily part of the day-to-day skillset of the standard civilian RACGP registrar or fellow.

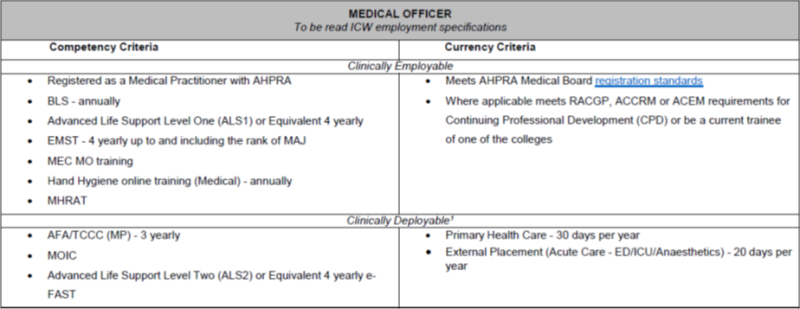

As part of the competency criteria to achieve employability, there is the requirement to maintain currency in Advanced Life Support (ALS) and Early Management of Severe Trauma (EMST). However, exposure to real world, high fidelity, clinical experience is necessary to put these foundations in place and work upon increasing the muscle memory required to perform certain emergency – often time critical – clinical skills. The current mitigation for this is for the GDMO to do 20 days per year of critical care placement at a civilian hospital – ideally one that sees a high proportion of critically ill trauma patients – in either an emergency, intensive care, or anaesthetic department. This is a specified currency criterion to achieve deployability, as outlined in the table below, drawn from the Army Standing Instruction (Personnel).

However, due to operational, exercise, or unit demands this is not always possible and is often waivered. Furthermore, there is difficulty in negotiating the opportunity to be released for a two-week period, and hence this placement block is often split up into standalone days spaced out across many months or even the entire year. In this scenario the training value is lost for a multitude of factors: skills are perishable, and one can lose proficiency unless performing them day after day; non-technical skills such as communication and personnel management suffer from discontinuity; and arguably most importantly, any rapport established with clinical supervisors, and the trust that accompanies this, may be lost if extended periods go by without contact. Additionally, 20 days of annual critical care placement is likely still inadequate for the expected level of clinical capability expected without direct supervision in remote, austere, and under-resourced operational environments.

As a solution to some of the problems outlined above, the concept of a three-month clinical placement block at a tertiary trauma hospital was explored, with the assistance of a military specialist program anaesthetist working at this hospital. This clinical placement consisted of being incorporated into the roster with a team of other hospital employed trauma registrars, as well as operating in a non-supernumerary capacity; something that is not often the case whilst on Defence associated clinical secondment. Naturally this consisted of after hours, weekends, and night shifts on a regular basis, all of which are necessary to foster autonomous clinical decision making and allow full exposure to the gamut of trauma presentations.

When considering the unique requirements of the GDMO, key benefits of the three-month clinical placement block include:

- Increasing comfort and competency in the initial assessment and management of the critically unwell patient. Through daily repetition of the primary survey (a foundation principle of EMST), on a minimum of 8-10 patients per shift, the process becomes ingrained and starts to become muscle memory.

- Exposure to lifesaving trauma interventions on a daily basis including, but not limited to: the insertion of wide-bore, rapid infusion intravenous access; the placement of anaesthetic nerve blocks for the management of fractured legs and ribs; facilitating the reduction of dislocated joints and fractured limbs under procedural sedation; and developing increasing competency with another vital skill in trauma – and a clinically deployable skill that is often waivered due to the availability of courses – the e-FAST ultrasound.

- Weekly involvement in the statewide trauma audit, a multidisciplinary meeting aimed at examining clinical decision making, morbidity and mortality case discussions, individual audits and registrar research projects, the end result of which is to ensure that the trauma policies and procedures in place are optimising patient care and improving these processes wherever possible.

- The multitude of non-clinical skills that come with working in this fast paced and stimulating environment. The ability to constantly develop individual leadership of small teams, fine tune communication in high stress environments, appreciate the flow of patient transport through clinical areas, all skills that have direct relevance in the military medical context, especially as we move forward with rethinking deployable health capabilities. Spending time in civilian hospitals further strengthens the relationship between Defence and external stakeholders and affords the opportunity for the GDMO to recruit the multitude of non-GP specialists that are required in the SERCAT 5 space for the Role 2 and up.

In conclusion, an RACGP-fellowed GDMO with critical care experience is likely the best fit for the Role 1 capability when all things are considered and is evident in the decades of this being the accepted status quo. Where the disconnect lies is in the expectations placed on the individual, and their subsequent access to meaningful training opportunities to feel comfortable in delivering this capability. Naturally, access to opportunities as described above requires a professional level of understanding from command and must be considered at a time when unit tempo permits, in order to balance organisational needs with the needs of the individual. With future deployments likely requiring the deployment of geographically dispersed, forward operating, low footprint, manoeuvrable medical capabilities, equipping GDMOs with these advanced skills can only enhance individual readiness, enhance capability, and most importantly improve the outcomes for trauma casualties.