Tactical success in any engagement will favour the side who is able to generate some form of relative advantage or superiority and use this to strike their enemy at a place of weakness. Relative advantage is underpinned by gaining and retaining the initiative in a conflict. Having the initiative enables the commander to act – as opposed to react – in a battlespace by providing time, space and information. The initiative, therefore, provides a commander with relative advantage, most often taking the form of either material or decision superiority. Material superiority is concentrating a greater mass of combat power or effect relative to the enemy, while decision superiority is concentrating a greater rate of relative action over the enemy, otherwise known as tempo. Decision superiority is usually more effective at deciding the outcome of offensive action than material superiority. A commander that possesses the initiative, and therefore decision superiority, may advance against a more powerful opponent as they are able to compel their materially superior adversary to react defensively to a greater rate of attacks, feints, or demonstrations at the expense of the opponent’s battle plan. Both material superiority and decision superiority are ways to measure who can gain the initiative, but to develop a deeper understanding of how to employ initiative, a commander must understand the inherent difficulty in obtaining it and the ease with which it can be lost. As junior leaders in 1915 and 1991, Leutnant Ernest Rommel and Captain H.R. McMaster, respectively, encountered situations where they took decisive offensive action in conflict and achieved tactical success. Both commanders used an aggressive attack to gain the initiative for their forces, which enabled their decision superiority in a situation where their enemy had material superiority.

Leutnant Ernest Rommel fought multiple battles as part of the invading Imperial German Army in France during WW1. Rommel chronicled his experiences in the 1937 book, 'Infanterie Greift An', which was widely read by both Allied and Axis commanders before and during WW2.[1] Rommel discusses his actions as a company commander in a battalion attack in the Argonne Woods on 29 January 1915.[2] His company, the 9th Company of the 2nd Battalion, 27th Division, was attacking a position of the French defensive line as part of a battalion offensive. The 9th Company had exploited approximately a mile past their line of departure through three major wire entanglements and defensive lines with minimal enemy resistance. At each obstacle emplacement, the enemy forces saw the advancing German infantry and withdrew, allowing the 9th Company to capture each successive defensive position. The remainder of the battalion met heavier resistance and only achieved limited success through the first defensive line. Rommel identified and occupied a strong defensive position which had been developed by the French defenders, approximately half a mile ahead of the remainder of the battalion, with mostly unbreached obstacle lines between the battalion and his company.

Rommel knew he needed ammunition and reinforcements from the battalion if this position was going to be maintained and his success exploited. He sent a runner for reinforcements and supplies and began developing the bridgehead. During this time, withdrawing French forces sporadically harassed the 9th Company, ultimately surrounding and attempting to retake the position with a battalion’s worth of men. The defence of this position was difficult with limited ammunition and no heavier tools to break through the icy ground. Rommel simultaneously received a contact report that the French were attempting to retake their positions from the west and the verbal message, 'Battalion is in position half a mile to the north and is digging in. Rommel’s company to withdraw, support not possible.' He quickly identified three possible actions since maintaining the position was untenable: surrender, withdraw, or attack. Rommel determined that surrender was not an option and assessed that the encircling French forces would cause 50% casualties on his company if they withdrew across the defensive works in their current situation. He decided the best course of action was to attack the French forces, then withdraw after successful offensive manoeuvre. Rommel quickly issued orders for the attack and used his reserve platoon to attack the right flank of the advancing French to the west, surprising and confusing the French, forcing them to withdraw. The 9th Company then withdrew through the three wire entanglements under sporadic fire from the eastern French forces and re-joined the battalion in their new position, suffering only five wounded throughout the entire withdrawal.

Rommel knew he needed ammunition and reinforcements from the battalion if this position was going to be maintained and his success exploited. He sent a runner for reinforcements and supplies and began developing the bridgehead. During this time, withdrawing French forces sporadically harassed the 9th Company, ultimately surrounding and attempting to retake the position with a battalion’s worth of men. The defence of this position was difficult with limited ammunition and no heavier tools to break through the icy ground. Rommel simultaneously received a contact report that the French were attempting to retake their positions from the west and the verbal message, 'Battalion is in position half a mile to the north and is digging in. Rommel’s company to withdraw, support not possible.' He quickly identified three possible actions since maintaining the position was untenable: surrender, withdraw, or attack. Rommel determined that surrender was not an option and assessed that the encircling French forces would cause 50% casualties on his company if they withdrew across the defensive works in their current situation. He decided the best course of action was to attack the French forces, then withdraw after successful offensive manoeuvre. Rommel quickly issued orders for the attack and used his reserve platoon to attack the right flank of the advancing French to the west, surprising and confusing the French, forcing them to withdraw. The 9th Company then withdrew through the three wire entanglements under sporadic fire from the eastern French forces and re-joined the battalion in their new position, suffering only five wounded throughout the entire withdrawal.

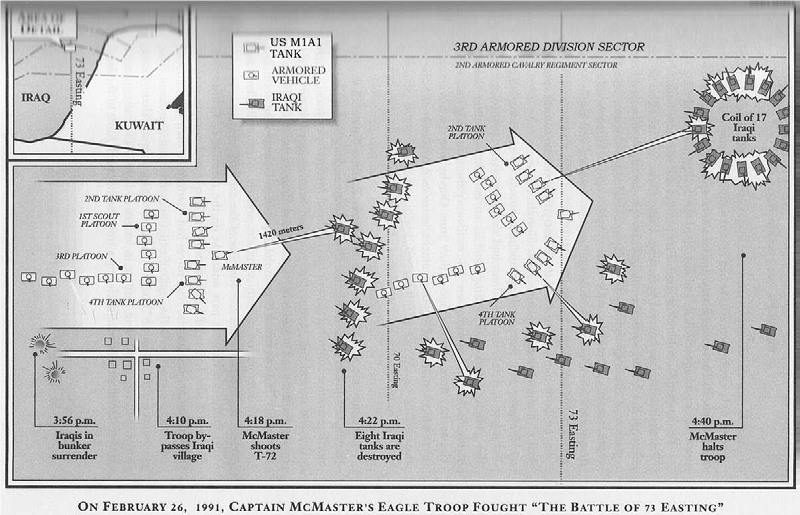

Some 76 years later, the US-led coalition intervened in the Iraqi annexation of Kuwait. There was a significant concern that the Iraqi Republican Guard (IRG) would provide a determined resistance to counter the US forces. According to the intelligence reports, the planning casualty estimates for the first major conflict for the US forces since Vietnam were considerably high.[3]In late February 1991, the 2nd Armoured Cavalry Regiment (2 ACR), part of a corps-sized manoeuvre, crossed the Saudi-Iraqi border and moved west to east to cut off IRG units retreating from Kuwait. On the afternoon of 26 February, Eagle Troop[4] of 2 ACR was given a limit of advance of the 70 Easting and a task to find the IRG units, but not to engage them in combat. The 2 ACR intent was to find the IRG and provide a hand-over to the armoured units of the 1st Infantry Division for destruction. Eagle Troop moved up to a small village just to the west of their boundary and received ineffective RPG and small arms fire from the village and quickly returned fire.  The commander of Eagle Troop, Captain H.R. McMaster, assessed that contact with IRG T-72s was imminent and reorganised his forces with tank platoons in the lead to provide the most firepower and protection on their advance.[5] At 1618 hours, Eagle Troop crested a low rise and encountered eight T-72 tanks in a dug-in defensive position on the 70 Easting, which they engaged with 120mm HEAT and SABOT rounds, destroying all eight in four minutes as they reached the 70 Easting. After this encounter, McMaster’s lead platoons identified further targets in depth and, determining that Eagle Troop was already in the close fight and wishing to exploit his success, McMaster ordered his troop to continue across their limit of advance. At the 73 Easting, they encountered 18 more T-72s in prepared positions and engaged them. By 1640 hours, Eagle Troop had destroyed these tanks and their mechanised infantry support before adopting a defensive position on the 74 Easting. In 23 minutes of combat, Eagle Troop had destroyed 28 Iraqi tanks, 16 personnel carriers and 30 trucks without a sustaining a single casualty[6]. Once having assumed the defensive position on the 74 Easting, Eagle Troop, as part of 2 ACR, then facilitated a forward passage of lines for the 1st Infantry Division before moving into reserve for subsequent operations.

The commander of Eagle Troop, Captain H.R. McMaster, assessed that contact with IRG T-72s was imminent and reorganised his forces with tank platoons in the lead to provide the most firepower and protection on their advance.[5] At 1618 hours, Eagle Troop crested a low rise and encountered eight T-72 tanks in a dug-in defensive position on the 70 Easting, which they engaged with 120mm HEAT and SABOT rounds, destroying all eight in four minutes as they reached the 70 Easting. After this encounter, McMaster’s lead platoons identified further targets in depth and, determining that Eagle Troop was already in the close fight and wishing to exploit his success, McMaster ordered his troop to continue across their limit of advance. At the 73 Easting, they encountered 18 more T-72s in prepared positions and engaged them. By 1640 hours, Eagle Troop had destroyed these tanks and their mechanised infantry support before adopting a defensive position on the 74 Easting. In 23 minutes of combat, Eagle Troop had destroyed 28 Iraqi tanks, 16 personnel carriers and 30 trucks without a sustaining a single casualty[6]. Once having assumed the defensive position on the 74 Easting, Eagle Troop, as part of 2 ACR, then facilitated a forward passage of lines for the 1st Infantry Division before moving into reserve for subsequent operations.

Decision superiority is enabled by initiative through the provision of time, space or information. Both Leutnant Ernest Rommel and Captain H.R. McMaster gained time and space for their elements as their key factors in gaining the initiative in their respective battles. Rommel bought time for his company through the fast and aggressive advance through the initial defensive positions and the subsequent occupation of a strong, previously developed defensive position. He then won space to allow the 9th Company the initiative to successfully withdraw by the conduct of limited offensive action. McMaster similarly gained time by the fast and aggressive assault through several IRG defensive positions before they could react, and space by occupying a significantly more advantageous position behind the initial IRG defensive line. In Rommel’s case, operational initiative was lost by the battalion’s decision to not exploit the 9th Company’s successful penetration of the subsequent obstacle belt, and instead the battalion consolidated in a defensive position on the first line of captured French defences. This decision was based on the information the battalion had at the time and the necessity to use time and space gained by the 9th Company to prepare for future offensive actions. For Eagle Troop, pushing significantly past their initial limit of advance was not as per the initial battle plan where Eagle Troop was ordered to halt and secure the 70 Easting. McMaster, apologising to his higher headquarters, passed through the specified limit of advance and continued his assault, retaining the initiative by denying nearby IRG forces the time to consolidate and effectively counter-attack. Again, McMaster’s higher headquarters lacked key information about the tactical success and situational awareness that Eagle Troop had at that time in the battle.

Rommel’s decision superiority stemmed from gaining initiative through a sound understanding of his opponent’s capabilities and their unwillingness to stand and fight. McMaster’s decision superiority was derived through speed of action, firepower, and denying time and space to an enemy who became unable to react to the situation. Rommel was at risk of losing the decision superiority and initiative when his company was culminating, and resupplies were not being sent forward. By engaging in offensive action and forcing a commander’s dilemma on the enemy he was able to create both time and space to conduct his withdrawal from an otherwise impossible situation. McMaster had passed his specified limit of advance; however, he assessed that he still retained the initiative and was well positioned to continue his assault. McMaster maintained decision superiority by denying time and space to allow the IRG to manoeuvre. The ferocity and speed of the attack resulted in the IRG being unable to comprehend their situation. If McMaster had followed his orders and remained at the 70 Easting, the IRG would have been well-positioned to counter-attack and take the initiative from 2 ACR.

Accelerated Warfare acknowledges that the contemporary and future battlespaces will be uncertain and highly contested across multiple domains.[7] Army needs to have decision superiority when operating across these uncertain domains in order to be successful in any mission. Future proofing Army will require initiative to be present at all levels, in all aspects of our work. This will enable us to remain competitive against any opponents, situations or environments that will impact our mission. If we do not actively plan on gaining and retaining the initiative in our routine training, we risk losing conflicts before they occur when material or decision superiority belongs to our opponent. Both the Battle in the Argonne and the Battle of 73 Easting exemplify a sub-unit commander’s initiative in successful exploitative manoeuvres. Similar to these examples, in Army a superior commander’s ability to empower their subordinate commanders with time, space and information will assist in enabling the decision superiority for the element. Conversely, a subordinate achieving decision superiority has the potential to create opportunities for the superior commander, but only if correctly conveyed to that commander. This is not just applicable on the battlefield, but also in barracks routine, headquarters operations and on training exercises.

This article was originally published in the CTC Live 2020 Fight to Win paper

ctc-live_2020_fight_to_win_papers.pdf