In response to Australia’s most challenging strategic circumstances since the end of the Second World War, Australia’s Government recently adopted a strategy of denial.[i] This strategy seeks to negate an enemy’s prospects of success, thereby dissuading them from attempting to threaten or coerce Australia. As the Australian Defence Force (ADF) adjusts its operational concepts to execute this strategy, one area worthy of consideration is ‘depth.’

Depth is an operational tenet where friendly forces extend the battlefield in time and space to attack uncommitted enemy elements and thereby limit an enemy’s freedom of action.[ii] ADF interdiction in depth will reduce an enemy’s potential to project and sustain military power in Australia’s immediate region – thereby enabling a strategy of denial.

Concurrent to adopting a strategy of denial, Australia also signalled its intent to pursue emerging technologies as a means of increasing military effectiveness.[iii] In particular, the Australian Government identified that Robotic and Autonomous Systems (RAS) are key emerging technologies that may enable the ADF to achieve an advantage in future conflict.[iv] As a broad overarching term, RAS are systems that comprise of physical (robotic) and/or cognitive (autonomous) elements.[v]

Unfortunately, Western militaries often acquire such technologies with a blind optimism that they will result in positive battlefield outcomes.[vi] Without a theory that guides the employment of RAS in Australia’s strategy, there is a risk that the ADF’s interest in RAS could follow a similar path.

The ADF lacks a theory that explains the relationship between RAS and depth, and this article fills that gap by linking the technology with Australia’s operational requirements. Looking forward, ADF force designers and operational planners should use RAS to achieve depth because limiting an enemy’s freedom of action is necessary for Australia’s strategy, and RAS operations that are daring, persistent, and adaptive will allow the ADF to generate superior depth.

Why should the ADF fight deep?

As an operational tenet, depth refers to the extension of the battlefield in time and space.[vii] By attacking uncommitted enemy elements in the deep area, a force reduces a threat’s freedom of action and opens windows of opportunity for decisive action. This is not a new concept. Soviet theorists during the interwar period arguably had the most significant impact on the theory of deep attack, and the Red Army effectively achieved depth to overwhelm German forces in the latter part of the Second World War.[viii]

For the United States (U.S.), depth has been at the core of their warfighting philosophy since 1982. In seeking to overcome Soviet numerical superiority, U.S. General Donn Starry envisaged extending the battlefield to engage uncommitted Soviet forces in the deep area, thereby opening windows of opportunity for decisive action by units of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).[ix] This approach was executed with prodigious success during Operation DESERT STORM in 1991,[x] and remains a tenet of U.S. Army operations to this day.[xi] Yet, depth is not a prominent theme in ADF doctrine – in fact, the ADF’s planning publication only briefly mentions the role of depth as part of sequencing operations.[xii] Notwithstanding this omission, achieving depth is a way of supporting Australia’s strategy of denial.

Australia’s strategy of denial aims to alter “any potential adversary’s belief that it could achieve its ambitions with military force at an acceptable cost.”[xiii] An enemy’s prospects of successfully coercing Australia are enabled by three factors. First, Australia’s primary area of military interest is a vast maritime space.[xiv] Second, Canberra cannot rely on a ten-year warning for a possible attack against Australia.[xv] Third, the ADF is of modest size and capability when compared to some other regional militaries.[xvi]

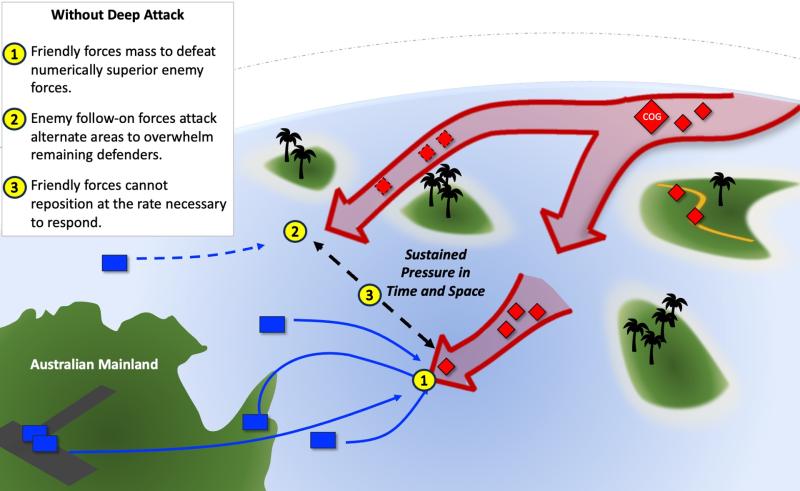

When combined, these factors present military planners with a challenging problem: how does a small military defend a large space with limited warning if attacked by a capable, numerically superior opponent? Unless Australia fights deep, a larger opponent can concentrate combat power at multiple points at a rate that cannot be matched by the ADF’s defensive capability. This problem is conceptually illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1: Defending Australia without Deep Attack.[xvii]

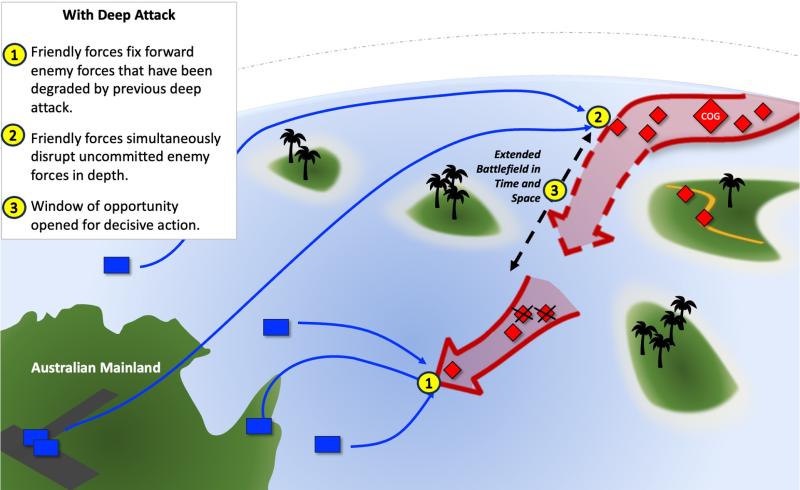

Just as General Starry wrestled with the prospect of larger Soviet forces overwhelming NATO defences in Europe during the Cold War, focusing ADF resources to attack an enemy in depth will disrupt an opponent’s ability to project and sustain forces in Australia’s immediate region (see figure 2). These disruptions will translate into windows of opportunity for even a small ADF to seize the initiative and act decisively to defeat elements of a larger opponent. The Australian Government’s emphasis on increasing the “range and lethality of the ADF” is consistent with an operational approach that fights deep,[xviii] and one specific technology area that could achieve depth is RAS.

Figure 2: Defending Australia with Deep Attack.[xix]

How do RAS achieve depth?

RAS are fundamentally different from human or crewed systems, and these distinctions present novel opportunities to extend the battlefield in time and space. The attributes that distinguish RAS from human or crewed systems are unique RAS characteristics, such as human safety, reach, signature, mass, and robustness.[xx] The unique characteristics of RAS allow a military force to affect uncommitted enemy forces in depth in ways that are normally regarded as infeasible due to human limitations or unacceptable because of the risk to human life.

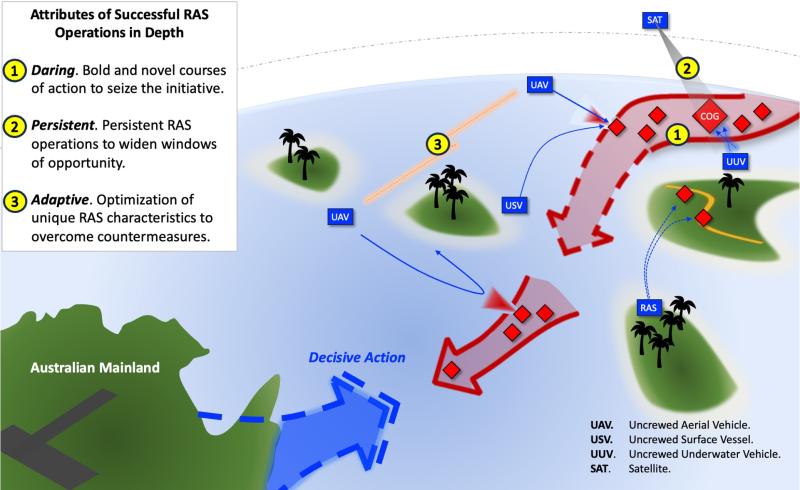

With this wider scope of options, a RAS-enabled military can wrest the initiative from an opponent earlier and open wider windows of opportunity for decisive action – an outcome that would otherwise be unachievable if they did not embrace these technologies. The relationship between RAS and depth is modelled in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Achieving Depth with RAS.[xxi]

Two unique RAS characteristics underpin the advantage offered by RAS in depth: human safety, and reach. All RAS have ‘human safety’ attributes because they can be employed as a substitute for humans in threat environments.[xxii] It follows that RAS allow militaries to pursue ‘daring’ courses of action and attack high-risk, high-reward enemy capabilities in the deep area because such actions do not endanger human lives. ‘Reach’ is a unique RAS characteristic because RAS are not restricted by human life support requirements.[xxiii] Long-range, long-endurance RAS allow militaries to achieve more persistent effects against uncommitted enemy forces in depth, which translates into wider windows of opportunity for decisive action in the close fight.

However, war is an interactive phenomenon. In recognising the advantages generated by RAS, the enemy will seek to implement kinetic and non-kinetic RAS countermeasures. To overcome these countermeasures, a military can emphasise three other unique RAS characteristics. First, RAS can exploit the characteristic of ‘signature.’ Signature is a system’s ability to be detected, and RAS have signature advantages because they can be designed to maximize mission performance without the need to account for human life support systems.[xxiv]

Through signature, RAS can deceive or infiltrate enemy countermeasures to conduct deep attack. Second, a military can use RAS en masse because these systems can be manufactured at a speed and scale that is difficult to replicate with human mobilisation, particularly in states with small populations.[xxv] Through mass, RAS can outnumber and overwhelm RAS countermeasures. Third, militaries can focus on the ‘robustness’ of RAS to withstand the effects of countermeasures. RAS have different physical and cognitive strengths and weaknesses when compared with humans,[xxvi] and RAS can undergo physical and electronic hardening to reduce their vulnerability to enemy effects.

Over the course of a conflict, the contest between friendly RAS and enemy RAS countermeasures will drive further adaptation as both parties seek to regain an advantage. Operations that are ‘adaptive’ will allow a force to rapidly reconfigure its RAS to accentuate the signature, mass, and robustness necessary for success. Thus, in totality, the underlying distinctions between RAS and human or crewed systems allow a force with an effective RAS capability to fight differently and achieve superior depth. The relationship between RAS and depth highlights that successful RAS operations in depth will be ‘daring,’ ‘persistent,’ and ‘adaptive.’ The Second Nagorno-Karabakh War and the Russo-Ukrainian War provide recent examples of this theory in practice.

During the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War in late 2020, Azerbaijan used its impressive fleet of uncrewed aerial vehicles (UAVs) to degrade Armenian military capabilities in depth and set the conditions for victory.[xxvii] Initially, upon the outbreak of conflict, Azerbaijan used the human safety and signature characteristics of its UAVs to destroy Armenia’s air defence capabilities in the disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh. In some instances, Azerbaijani pilots converted aging An-2 biplanes into UAVs, which they subsequently flew on daring flight paths to stimulate Armenian air defence systems.[xxviii]

Perhaps more importantly, Armenia’s disjointed air defence network was unable to detect Azerbaijan’s smaller one-way attack (OWA) UAVs,[xxix] which infiltrated and destroyed most of Armenia’s countermeasures. With a permissive airspace, Azerbaijan used the reach of its long-range long-endurance TB2 Bayraktar UAVs to achieve near persistence surveillance on Armenia’s lines of communication.[xxx]

The TB2 Bayraktars destroyed uncommitted Armenian artillery, transport, and armoured reserves, which created critical supply shortages for forward Armenian defenders. In total, at least forty-three percent of Armenia’s total equipment losses can be attributed to Azerbaijan’s UAVs.[xxxi] As Armenian capacity to fight degraded over time, Azerbaijan opened wide windows of opportunity for its ground forces to make rapid territorial gains. After just 44 days, the conflict ended in Baku’s favour.

Despite Azerbaijan’s overwhelming success in employing RAS, Ukraine’s RAS were less effective in depth just three years later. In 2023, Kyiv initiated a long-anticipated counteroffensive as part of the Russo-Ukrainian War.[xxxii] As part of its operations in depth, Ukraine used RAS in two ways. First, Ukraine struck cities and airfields within Russia through the reach of long-range OWA UAVs and forward deployed covert operators with short-range UAVs.[xxxiii] While the attacks probably disturbed Russia’s sanctuary for military operations, many of the long-range OWA UAVs were destroyed by Russian countermeasures and the operational benefit of the deep strikes was unclear.

Second, Ukraine used air and maritime RAS to degrade Russia’s operational support in Crimea and the Black Sea. The signature and human safety characteristics of Ukrainian uncrewed surface vessels enabled daring deep attacks that successfully degraded Russia’s Black Sea Fleet.[xxxiv] However, Ukraine’s attacks against Russian military capabilities and lines of communication on land were less effective. Successful deep attacks against land targets often only occurred when Ukraine used exquisite RAS and/or combined different RAS to overwhelm Russian countermeasures.[xxxv]

Although the cumulative effect of Ukraine’s attacks in Crimea and the Black Sea likely opened a narrow window of opportunity for decisive action in August and September 2023, there was probably a misalignment between Ukraine’s deep operations and their capacity to exploit the resulting advantage in the close fight.[xxxvi] The ultimate failure of Ukraine’s 2023 counteroffensive illustrated that practitioners of operational art must align their operational approach with the opportunities presented by new technologies. It is in the context of these recent examples that the ADF should examine how it intends to employ RAS in support of Australia’s strategy of denial.

What actions should Australia take to fight deep with RAS?

If one accepts, as this article contends, that Australia requires the capability to extend the battlefield in time and space to execute a strategy of denial, then it follows that it would be prudent for the ADF to consider the opportunities presented by RAS in achieving depth. This conclusion does not mean the ADF should immediately acquire cutting-edge RAS technologies. In fact, it would be counterproductive to purchase or develop new RAS for the sake of innovation without the underlying logic that translates the unique RAS characteristics into military advantage.[xxxvii] Instead, the ADF should start with re-examining its operational concepts with the perspective that successful RAS operations in depth will be daring, persistent, and adaptive.

As an illustration of how RAS operations in depth may reshape Australia’s operational approach, one could conceive of the ADF deploying long-range, long-endurance RAS along Australia’s lines of communication prior to conflict to mitigate Australia’s loss of strategic warning time. In the event of conflict, ADF RAS could present a persistent threat to enemy power projection capabilities and lines of supply. Moreover, the ADF could employ RAS in daring attacks on enemy centres-of-gravity and critical vulnerabilities in the early stages of a campaign to wrest the initiative and cause an opponent to re-distribute their combat power to protect their rear areas.

Using an adaptive approach, the ADF could use interactions with the enemy to detect their countermeasures and reconfigure RAS to accentuate the right combination of unique RAS characteristics to overwhelm enemy defences in successive actions. By emphasising the unique characteristics of RAS to fight in ways that are daring, persistent, and adaptive, the ADF can open wide windows of opportunity for decisive action against remaining enemy elements. This conceptualisation is in figure 4.

Figure 4: Conceptual Depiction of ADF RAS Operations to Achieve Depth.[xxxviii]

This paper does not seek to dictate Australia’s operational concepts. However, looking forward, the ADF should:[xxxix]

- Recognise the unique characteristics that RAS affords militaries to fight in novel ways.

- Acknowledge militaries with an effective RAS capability will generate greater depth.

- Design new concepts that use RAS in depth in ways that are daring, persistent and adaptive.

Despite these recommendations, the ADF should not ignore exploring the utility of RAS in the close and rear areas. The ADF’s promising research and development in fields such as autonomous logistics and optionally crewed combat vehicles will certainly enhance the ADF’s capability in the future.[xl] Nevertheless, the deep fight is critical to the ADF’s capacity to meet Australia’s recent strategic guidance and RAS offer an advantage in the high threat environments beyond the front lines. Without a dedicated focus on the deep fight, there is a risk that Australia’s military thinking will be disproportionately influenced by combat footage of quadcopters in Ukraine, rather than the realities of Australia’s strategic environment.

Conclusion

As it transitions to meet the Australian Government’s recent strategic guidance, the ADF should not assume that emerging technologies will solve Australia’s military problems. However, it would be equally unwise to dismiss the role these technologies may play in future warfare. This article contends that the unique characteristics of RAS will allow the ADF to fight in novel ways. With RAS operations that are daring, persistent and adaptive, the ADF can limit an enemy’s ability to project and sustain military power near Australia. The resulting windows of opportunity will support the ADF’s efforts to fight and win in challenging strategic circumstances.

More broadly, this article highlights that emerging technologies can inspire original thought on the application of military power. The best militaries use emerging technology as an intellectual stimulus to design new operational concepts that guide the transformation necessary to overcome their adversaries. Thought, not just technology, will be essential for the ADF to prevail in these uncertain times.

Bibliography

Australian Army, Robotic and Autonomous Systems Strategy (v2.0, Canberra: Australian Army, August 2022).

Australian Defence Force, Concept for Robotic and Autonomous Systems (version 1.0, Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2020).

Australian Defence Force, Joint Military Appreciation Process, Australian Defence Force Procedures 5.0.1 (ed. 2, Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, August 15, 2019).

Australian Government, National Defence: Defence Strategic Review (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023), https://www.defence.gov.au/about/reviews-inquiries/defence-strategic-re….

Australian Government, Integrated Investment Program (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2024), https://www.defence.gov.au/about/strategic-planning/2024-national-defen….

Australian Government, National Defence Strategy (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2024), https://www.defence.gov.au/about/strategic-planning/2024-national-defen….

Baker, G., ‘Ukrainian Drone Destroys Russian Supersonic Bomber,’ BBC News (August 22, 2023), https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-66573842.

Barber, N., ‘Beyond Human: Achieving Depth with Robotic and Autonomous Systems,’ master’s thesis [unpublished], U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, KS, 2024.

Bruscino, T., ‘American and Joint Origins of Operational Depth,’ Expeditions with Marine Corps University Press (July 23, 2021), https://doi.org/10.36304/ExpwMCUP.2021.05.

de Pury, K. ‘It’s Not the Drone Strikes That Hurting Moscow, It’s the Traffic Jams,’ The Economist (September 22, 2023), https://www.economist.com/1843/2023/09/22/its-not-the-drone-strikes-tha….

Department of Defence, ‘Army’s Autonomous Truck Convoy a First,’ Defence Australia, accessed August 13, 2023, https://www.defence.gov.au/news-events/news/2023-06-09/armys-autonomous….

Dortmans, P. et al., Supporting the Royal Australian Navy’s Strategy for Robotics and Autonomous Systems: Building an Evidence Base (Canberra: RAND Australia, 2021), https://doi.org/10.7249/RR-A929-1.

Erickson, E., ‘The 44-Day War in Nagorno-Karabakh: Turkish Drone Success or Operational Art?’ Military Review Online Exclusive (August 2021), https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/img/Online-Ex….

Glantz, D., ‘Soviet Operational Formation for Battle: A Perspective,” in J. Kem, ed., Deep Operations: Theoretical Approaches to Fighting Deep (Fort Leavenworth, KS: Army University Press, 2021), 59–74.

Headquarters, Department of the Army, Operations, Field Manual (FM) 3-0 (Fort Belvoir, VA: Army Publishing Directorate, October 2022)

Hecht, E., “Drones in the Nagorno-Karabakh War: Analyzing the Data,” Military Strategy Magazine, 7/4 (Winter 2022), 31-38.

Institute for the Study of War, “Ukraine Daily Conflicts Updates 2023,” (December 31, 2023), https://www.understandingwar.org/ukraine-conflicts-updates-2023.

Isserson, G., “Foundations of Deep Strategy,” in J. Kem, ed., Deep Operations: Theoretical Approaches to Fighting Deep (Fort Leavenworth, KS: Army University Press, 2021), 15-40.

Kofman, M. & R. Lee, ‘Perseverance and Adaptation: Ukraine’s Counteroffensive at Three Months,’ War on the Rocks (September 04, 2023), https://warontherocks.com/2023/09/perseverance-and-adaptation-ukraines-….

Office of the Secretary of Defense, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China, 2023: Annual Report to Congress (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 2023).

Prysiazhniuk, V., “The SBU Confirmed the Attack on the Saki Military Airfield in Occupied Crimea,” Suspiline Crime (September 21, 2023), https://suspilne.media/577137-v-sbu-pidtverdili-udar-po-vijskovomu-aero….

Rubin, U., The Second Nagorno-Karabakh War: a Milestone in Military affairs (Mideast Security and Policy Studies 184. Ramat Gan: The Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies, 2020).

Sauer, P. & H. Sullivan, ‘Drone Strikes Moscow Building as Region Hit By Sixth Successive Night of Attacks,’ The Guardian (August 23, 2023), https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/aug/23/central-moscow-building-h….

Schneider, J. & J. Macdonald, ‘Looking Back to Look Forward: Autonomous Systems, Military Revolutions, and the Importance of Cost,’ Journal of Strategic Studies (January 24, 2023), https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2022.2164570.

Starry, D., ‘Extending the Battlefield,’ in J. Kem, ed., Deep Operations: Theoretical Approaches to Fighting Deep (Fort Leavenworth, KS: Army University Press, 2021), 107-128.

The Economist, ‘Is Ukraine’s Counter-Offensive Over?’ (November 09, 2023), https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2023/11/09/is-ukraines-counter….

The Washington Post, ‘Miscalculations, Divisions Marked Offensive Planning by U.S., Ukraine,’ (December 04, 2023), https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/12/04/ukraine-counteroffensiv….

Torossian, B. et al., ‘The Military Applicability of Robotic and Autonomous Systems,’ in Capstone Report: Robotic and Autonomous Systems in a Military Context (Hague: Hague Centre for Strategic Studies, January 2021), https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep29554.4.

United States Army, US Army Robotics and Autonomous Systems Strategy (Fort Eustis, VA: United States Army Training and Doctrine Command, March 2017).

Velimmadov, M., ‘Air Force, Air Defence, and Electronic Warfare in Second Karabakh War,’ Caliber (October 07, 2022), https://caliber.az/en/post/113722/.

Watling, J., ‘MWI Podcast: The Conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh is Giving Us a Glimpse into the Future of War,’ in J. Amble, Modern War Institute, podcast, 35:22 (October 14, 2020), https://mwi.westpoint.edu/mwi-podcast-the-conflict-in-nagorno-karabakh-is-giving-us-a-glimpse-into-the-future-of-war/.

End Notes

[i] Australian Government, National Defence Strategy (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2024), 22, https://www.defence.gov.au/about/strategic-planning/2024-national-defen….

[ii] Headquarters, Department of the Army, Operations, Field Manual (FM) 3-0 (Fort Belvoir, VA: Army Publishing Directorate, October 2022), p. 3-12.

[iii] Australian Government, National Defence Strategy, 15, 63-65.

[iv] The Australian Government plans to invest billions of dollars in RAS over the next decade. See Australian Government, Integrated Investment Program (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2024) 21, https://www.defence.gov.au/about/strategic-planning/2024-national-defen….

[v] Australian Defence Force, Concept for Robotic and Autonomous Systems (Version 1.0, Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2020), 71.

[vi] J. Schneider & J. Macdonald, ‘Looking Back to Look Forward: Autonomous Systems, Military Revolutions, and the Importance of Cost,’ Journal of Strategic Studies (January 24, 2023), https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2022.2164570.

[vii] The official U.S. Army definition of depth is “the extension of operations in time, space, or purpose to achieve definitive results.” See Headquarters, Department of the Army, Operations,Field Manual 3-0 (Fort Belvoir, VA: Army Publishing Directorate, 2022), p. 3-7.

[viii] D. Glantz, ‘Soviet Operational Formation for Battle: A Perspective,’ in J. Kem, ed., Deep Operations: Theoretical Approaches to Fighting Deep (Fort Leavenworth, KS: Army University Press, 2021), 59–74.

[ix] D. Starry, ‘Extending the Battlefield,’ in J. Kem, ed., Deep Operations: Theoretical Approaches to Fighting Deep (Fort Leavenworth, KS: Army University Press, 2021), 107-128.

[x] T. Bruscino, ‘American and Joint Origins of Operational Depth,’ Expeditions with Marine Corps University Press (July 23, 2021), https://doi.org/10.36304/ExpwMCUP.2021.05.

[xi] Headquarters, Department of the Army, Operations,Field Manual 3-0 (Fort Belvoir, VA: Army Publishing Directorate, 2022), p. 3-7.

[xii] Australian Defence Force, Joint Military Appreciation Process, Australian Defence Force Procedures 5.0.1 (ed. 2, Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, August 15, 2019), p. 4-11.

[xiii] Australian Government, National Defence Strategy, 22.

[xiv] Australia’s primary area of military interest was described in the National Defence Strategy. See Australian Government, National Defence Strategy, 21; P. Dortmans et al., Supporting the Royal Australian Navy’s Strategy for Robotics and Autonomous Systems: Building an Evidence Base (Canberra: RAND Australia, 2021), 5-6, https://doi.org/10.7249/RR-A929-1.

[xv] Australian Government, National Defence: Defence Strategic Review (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023), 24-25, https://www.defence.gov.au/about/reviews-inquiries/defence-strategic-re…

[xvi] As an example, the People’s Liberation Army significantly outnumbers the ADF. See Office of the Secretary of Defense, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China, 2023: Annual Report to Congress (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 2023).

[xvii] Created by author.

[xviii] Australian Government, National Defence Strategy, 21.

[xix] Created by author.

[xx] The most extensive analysis of RAS characteristics can be found in B. Torossian et al., ‘The Military Applicability of Robotic and Autonomous Systems,’ in Capstone Report: Robotic and Autonomous Systems in a Military Context (Hague: Hague Centre for Strategic Studies, January 2021), 27-28, https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep29554.4.

[xxi] Created by author. See N. Barber, ‘Beyond Human: Achieving Depth with Robotic and Autonomous Systems,’ 132.

[xxii] B. Torossian et al., ‘The Military Applicability of Robotic and Autonomous Systems,’ 34.

[xxiii] Reach is a combination of range and endurance. See B. Torossian et al., ‘The Military Applicability of Robotic and Autonomous Systems,’ 34.

[xxiv] Signature is not considered in B. Torossian et al.’s study; however, it is discussed under the heading of ‘stealth’ in Australian Defence Force, Concept for Robotic and Autonomous Systems, 27.

[xxv] B. Torossian et al., ‘The Military Applicability of Robotic and Autonomous Systems,’ 34.

[xxvi] The U.S. Army and the Australian Army identified that RAS fatigue differently to humans, and could be used to reduce the physical and cognitive burden on soldiers. United States Army, US Army Robotics and Autonomous Systems Strategy (Fort Eustis, VA: United States Army Training and Doctrine Command, March 2017), 1; Australian Army, Robotic and Autonomous Systems Strategy, (v2.0, Canberra: Australian Army, August 2022), 9.

[xxvii] E. Erickson, ‘The 44-Day War in Nagorno-Karabakh: Turkish Drone Success or Operational Art?’ Military Review Online Exclusive (August 2021): 2-3, https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/img/Online-Ex….

[xxviii] M. Velimmadov, ‘Air Force, Air Defence, and Electronic Warfare in Second Karabakh War,’ Caliber (October 07, 2022), https://caliber.az/en/post/113722/.

[xxix] U. Rubin, The Second Nagorno-Karabakh War: a Milestone in Military affairs (Mideast Security and Policy Studies 184. Ramat Gan: The Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies, 2020), 9.

[xxx] J. Watling, ‘MWI Podcast: The Conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh is Giving Us a Glimpse into the Future of War,’ in J. Amble, Modern War Institute, podcast, 35:22 (October 14, 2020), https://mwi.westpoint.edu/mwi-podcast-the-conflict-in-nagorno-karabakh-….

[xxxi] E. Hecht, ‘Drones in the Nagorno-Karabakh War: Analyzing the Data,’ Military Strategy Magazine,7/4 (Winter 2022), 31-38.

[xxxii] ‘Miscalculations, Divisions Marked Offensive Planning by U.S., Ukraine,’ The Washington Post (December 04, 2023), https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/12/04/ukraine-counteroffensiv…; ‘Is Ukraine’s Counter-Offensive Over?’ The Economist (November 09, 2023), https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2023/11/09/is-ukraines-counter….

[xxxiii] K. de Pury, ‘It’s Not the Drone Strikes That Hurting Moscow, It’s the Traffic Jams,’ The Economist (September 22, 2023), https://www.economist.com/1843/2023/09/22/its-not-the-drone-strikes-tha…; P. Sauer & H. Sullivan, ‘Drone Strikes Moscow Building as Region Hit By Sixth Successive Night of Attacks,’ The Guardian (August 23, 2023), https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/aug/23/central-moscow-building-h…; G. Baker, ‘Ukrainian Drone Destroys Russian Supersonic Bomber,’ BBC News (August 22, 2023), https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-66573842.

[xxxiv] Institute for the Study of War, ‘Ukraine Daily Conflicts Updates 2023,’ (December 31, 2023), https://www.understandingwar.org/ukraine-conflicts-updates-2023.

[xxxv] See for example V. Prysiazhniuk, ‘The SBU Confirmed the Attack on the Saki Military Airfield in Occupied Crimea,’ Suspiline Crimea (September 21, 2023), https://suspilne.media/577137-v-sbu-pidtverdili-udar-po-vijskovomu-aero….

[xxxvi] Ukrainian units chose a deliberate, dismounted offensive when confronted with strong Russian defensive fortifications. See M. Kofman & R. Lee, ‘Perseverance and Adaptation: Ukraine’s Counteroffensive at Three Months,’ War on the Rocks (September 04, 2023), https://warontherocks.com/2023/09/perseverance-and-adaptation-ukraines-….

[xxxvii] J. Schneider & J. Macdonald, ‘Looking Back to Look Forward: Autonomous Systems, Military Revolutions, and the Importance of Cost,’ 162.

[xxxviii] Created by author. See N. Barber, ‘Beyond Human: Achieving Depth with Robotic and Autonomous Systems,’ 138.

[xxxix] These recommendations should be accompanied by other measures to integrate RAS into a broader operational approach. See N. Barber, ‘Beyond Human: Achieving Depth with Robotic and Autonomous Systems,’ 138-139.

[xl] See for example Australian Army, Robotic and Autonomous Systems Strategy, 8; Department of Defence, ‘Army’s Autonomous Truck Convoy a First,’ Defence Australia, accessed August 13, 2023, https://www.defence.gov.au/news-events/news/2023-06-09/armys-autonomous….

For this technology to be as useful as is hoped in this article, a steady stream of components, especially microchips, will need to come from the same direction as the adversary. There is a reasonable chance that the friendly nations we rely on, Taiwan, South Korea and Japan, will themselves be busy and not able to supply us in the event there is a regional conflict.

Hence, the very scenario that would require RAS for a depth effect, simultaneously precludes the extended use of RAS.