Peter Bowles recently wrote a great article on ways to enhance the way we train our future combatants. His article is a useful starting point to ensure that we keep discussions on the improvement of the shooting continuum going, so that we as an Army can meet the Chief of Army’s intent of Ready Now, Future Ready. We personally believe that as an Army we are heading in the right direction when it comes to training an All Corps Combatant in the shooting continuum.

Blocked Training

The Rifle Practices (RP’s) and close shooting techniques that are currently taught at ab initio training establishments are utilising the blocked training method as described in the article. We are achieving superior results compared to the previous Live Fire practices. Here at the Royal Military College, the cadets complete the initial weapon qualification and then the Rifle Practices up to Rifle Practice 3A with over 80% achieving first time pass rates. The blocked training method is the only way we can achieve the desired results of the shooting continuum within the training establishments.

The RP’s were introduced to replace the live fire practices, which were not meeting the standard required to test a combatant when engaging and neutralising threats at different ranges whilst utilising cover. As we know Rifle Practice 1 – 6 are designed as stages of progression to further the shooters' abilities prior to attempting the combative shoots of Rifle Practice 3A or 6A

Rifle Practice Assessment Table

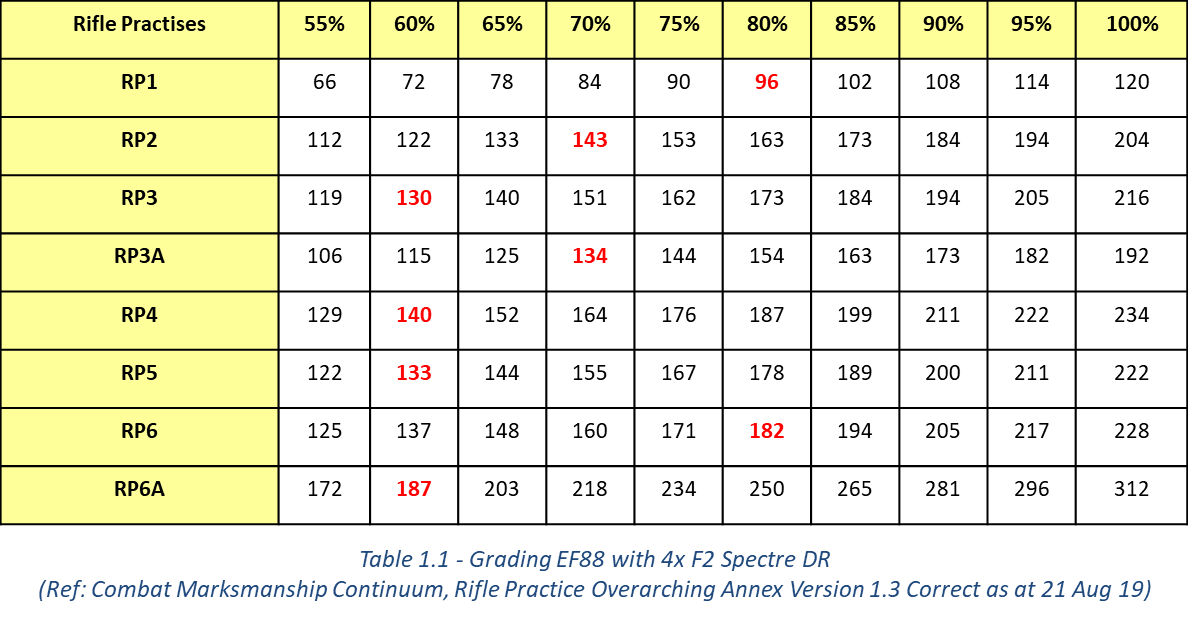

Table 1.1 demonstrates the percentage standards a firer should meet during the Rifle Practice as a sliding scale,. It is up to the commander’s discretion on the standard that they want their subordinates to achieve during that period of training.

The Rifle Practice Overarching Annex states that:

The Rifle Practice Overarching Annex states that:

Scoring requirements are based on the Mounting HQ requirements, or on the Formation Commander requirements. Consideration to the setting of standards should be given to the primary role of the combatant (either being an All Corps Combatant, Combined Arms Combatant or Dismounted Combatant), and their operating role. Specifically:

• All Corps Combatant (ACC): Neutralise threats at 100 m and suppress threats out to 300m

• Combined Arms Combatant (CAC): Neutralise threats out to 300m

• Dismounted Close Combatant (DCC): Neutralise threats out to 300m and suppress threats out to 600m

For example, upon determining the threat level the formation (or unit) will be operating in, the Commander may determine (due to the low threat nature) that its ACC only require a 50% grading, that its CAC require a 60% and its DCC require 70% of RP3A. Alternatively, the Commander may determine that (due to the high threat profile), its ACC will be operating in secure FOBs and require 55% of the banding of RP3A, but its CAC and DCC personnel will be exposed to a higher level of threat and require 70% of RP3A and RP6 respectively.

To provide context to the table, the example practice being fired is on a Marksmanship Training Range (MTR) with 200m moving targets. The scores in red are the minimum standard expected of a trainee at an ab initio training establishment.

The Rifle Practice grouping practice, which is utilised as the AIRN shoot, has been tiered as suggested in the Peter Bowles article. This is the standard to be used when the practice is fired as a test (i.e AIRN) as is described within the Rifle Practice grouping brief (1).

EF88 with Enhanced Day Sight (EDS):

1. All Corp Combatant (ACC) – 150mm or less

2. Combined Arms Combatant (CAC) – 150mm or less

3. Dismounted Close Combatant (DCC) – 100mm or less (75mm or less for a designated marksman)

In regards to providing feedback to the shooter on how they went during the conduct of the all Rifle Practice shoots, this can be done by implementing a small arms coach or another firer to provide feedback whilst also assessing combat behaviours, as we never fight alone. This technique is described within the Rifle Practice 3A Combatant assessment brief (2).

I would argue that Rifle Practice 3A is a mix between the two training methods that is described in the Peter Bowles article, as the firer is only given the initial combatants brief and then told to adopt different positions from the OIC during the practice. The firer then needs to engage targets as they appear at ranges from 100-300m, prioritising the engagement with the most dangerous threat first.

Interleaved Training

In reference to the examples of interleaved training in the article, a review of LWP-G 7-7-8 Train the Battle Shot will show that the rifle practices are only stage two of the shooting continuum (being elementary application of fire) and form the basic requirements that a combative must achieve before moving onto the next stages (3).

Stage four and five, being individual and team battle shooting, are where I believe the Interleaved Training method can be achieved. Current range doctrine, being both LWP-G 7-3-0 and 7-3-1, allow user-designed ranges to occur that would meet the example within the article of providing the soldiers with very little information before they engage the targets (4, 5).

An example of this is a range that we designed this year at RMC-D. We developed a user-designed practice by submitting a range danger trace utilising a firing line and then placed out mechanical targets at various ranges from 50 – 400m. The firing line was on the side of a hill with the targets being in the low ground. The cadets were utilising M4 rifles with iron sights and had to guess the range of all the different targets within their sectors prior to engaging them. This was a good way to incorporate judging ranges into the practice as well.

This basic range took very little time to plan and organise and would meet the intent of training soldiers in the Interleaved Training method. It can even have the same user-designed training conducted within the WTSS and on Permanent Basic ranges by speaking with the operators, noting the caveat of complying with Range Doctrine and Training Area Standing Orders (TASO).

Conclusion

We have a lot of freedom when it comes to designing training for our subordinates and at times doctrine is viewed as a constraint to being able to train effectively without having a full understanding of what can actually be achieved safely. The article by Peter Bowles described an effective way to train; the our aim of this reply is to provide further guidance on how this can be achieved within the current shooting continuum.

This article was co-authored with Warrant Officer Class Two Peter Turnbull