Peter Drucker (1973) says the purpose of business is to create and keep customers. If military service is looked at through a business lens, and its soldiers are considered its customers, is the purpose of an Army actually to create (recruit) and keep (retain) soldiers? Drucker’s view puts customers central and argues that by knowing who they are and what is valuable to them, a business will stay focused on why it exists and not the objectives it seeks (Vohra & Mukul, 2009). Success comes from a solid customer base that is loyal to that business. This in turn generates consistent sales. If a company has customers then sales will follow. In comparison, an Army’s role and mission to train, fight and protect the country's national interests. This becomes a commodity that can attract or detract customers (soldiers). However, fixating on these objectives can create a climate where people feel they are not central to the organisation but a means to an end. In line with Drucker’s logic, if an Army has customers (soldiers) then its role and mission will follow.

This article will open a conversation to ask the question, 'do we understand the workforce that seeks service in the Australian Army?' The aim of the article is not to assess the demographic that provides the gene pool to select from. Instead, it will provoke thought to query the methodology that determines what is important to create and keep soldiers.

Recruiting and Retention

Workforce analysis requires close attention that attracts and creates data that reflects choices made by the workforce and society. Like any organisation, a military competes with other employment options to generate interest and employee prospects. Assessing the market presents a science and art approach and requires knowledge and timeliness to achieve manpower targets. Reaching desired outcomes can be difficult and are influenced by numerous observed environmental impacts and, at times, unidentifiable conditions. Granted, specific detail may explain the atmospherics that contribute to these situations, but the focus of this article is to consider that the framework may not be optimal.

Markey (2020) reinforces the importance of tracking and disclosing customer value of a business. He reports that businesses often choose not to measure this due to cost and difficulty of gathering data. Instead, businesses rely heavily on productivity and the bottom line to identify effectiveness, which is not necessarily an indicator of workplace attitudes. Reflecting on Drucker’s view, if customers are satisfied then a business will be profitable; therefore, the bottom line will look after itself. An example of this resides within the Australian Army’s Aviation capability that has used a Snapshot climate assessment tool for several years to understand and ensure airworthiness and safety. The Snapshot gathers data on the impressions, beliefs and values of the workforce allowing commanders and leaders to investigate and apply remediation to improve the findings. In this case, listening and adjusting to employee feedback has engendered a culture of putting people first to achieve an operational output. Likewise, the Australian Army uses surveys such as the census and climate surveys that also gather data. These do inform the larger organisation but are not seen as tools that hold commanders accountable to improve work conditions. The utility of such surveys should capitalise on multiple applications, especially if an organisation considers the views of people (customers) central to addressing workplace issues.

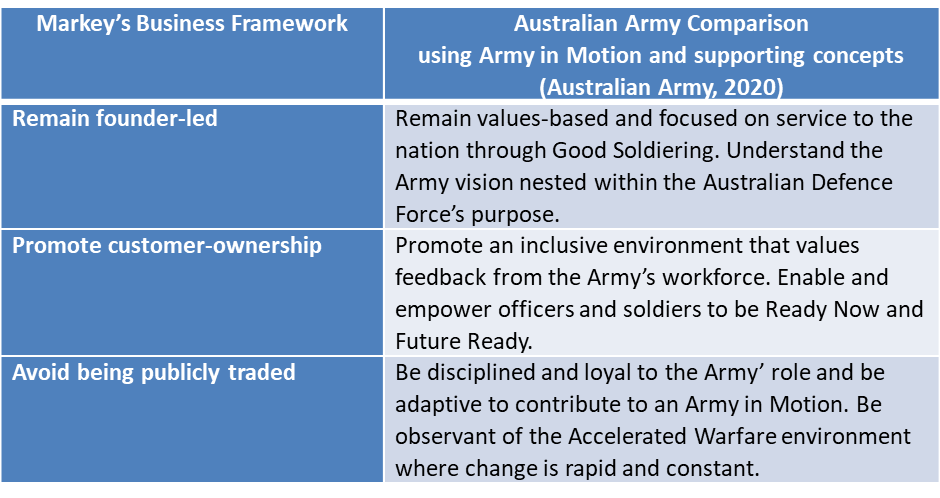

If this premise is accepted, Markey (2020) provides a simple framework that allows businesses to stay true to its customers and resist pressure from external stakeholders that seek an emphasis on structure and profit. Below is a comparison of Markey’s business perspective and the Australian Army’s 'Army in Motion' model through adherence to 'Good Soldiering':

For many, these elements may seem tokenistic and not translate into the needs and wants of individuals within the workforce. But what they do offer is a framework that is people centric. Essentially, when communicated within a consistent message of people being the best they can be to achieve understood and believable goals, then the workforce will feel they are central to the organisation.

If Army recruiting and retention is acknowledged to be under constant pressure from external influences, should the question be asked, 'is the Army message not resonating with its customers (soldiers)?' Markey (2020) makes several observations that would cause customers to feel undervalued:

- Allowing structure to put functional priorities ahead of customer (soldier) needs

- Not listening to the needs of customers (soldiers)

- Not persisting in articulating an inspiring vision, not planning a path to move towards that vision, and failing to engage the workforce

- Working in silos that inhibit seeing the environment through the eyes of customers (soldiers), which does not support rapid adjustment (Markey labels this as Design Thinking)

Reflection on Markey’s research, and its applicability to the Army’s approach to recruiting and retention, would assist to dissect the Defence Workforce Report. However, data alone does not have all the answers and should be analysed in consultation with reliable, personal accounts from across the workforce. As an example, in recent years, tempo management has emerged as a continual threat voiced by the workforce. It presents a threat to the welfare and livelihoods of individuals, the ability for teams to train and (possibly) for the organisation to retain soldiers. Much has been done to review and reduce external strains that draw people away from home locations but Markey’s observations may further assist with other elements that contribute to retention issues.

Conclusion

Conducting military training and operations is a people venture. Signs exist to raise concerns that current trends of recruiting and retention underachievement will continue. Understanding the existing workforce and the needs of recruit candidates requires awareness gained through the eyes of the workforce. Climate assessments assist to provide useable insight that allow commanders and leaders to design remediation plans. Rigid adherence to organisational structure, pressure from external stakeholders, ineffective communications, an uninspiring vision, and isolated decision making contribute to a workforce that feels undervalued. Peter Drucker sees customers as key to a business, which appropriately translates to officers and soldiers being key to an Army. Focusing on objectives and not the workforce does not prepare the Army to be Future Ready.