‘Augmented’ long-range fires (LRF) are an inherent and vital capability of Australia’s Combined Arms Fighting System. LRF are defined as an attack initiative conducted at distances significant enough to produce strategic effects – aligned with national deterrence and defence goals – rather than merely tactical or short-range engagements.

As a result, human-machine teaming (HMT), which involves the synergy of human and machine-based analysis to expedite decision-making processes, and the use of artificial intelligence (AI) to conduct ethical target acquisition, must be understood to meet the rising strategic competition presented by our adversaries.

The utility of HMT in target acquisition must not come at the cost of Australia’s ethical decision-making processes and reputation within the international community. Where technology can enhance our abilities to apply discriminatory and precision strikes, Australia must uphold the Laws of Armed Conflict (LOAC). We can do so through the observation and analysis of other key states’ employment of AI-enhanced targeting processes.

This article aims to engage the audience on the ethics of targeting amid technological advancements and their application in modern conflicts. It will conclude by offering considerations for the ADF’s future ethical approach to targeting processes.

A Case Study: The Israeli Defence Force

The Israeli Defence Force’s (IDF) ‘Lavender’ and ‘Gospel’ target acquisition platforms illustrate the rapid integration of AI into traditional battlefield sensors and intelligence-gathering methods. Accelerating a commander’s OODA loop and understanding of the ‘kill-chain’, augmented fires facilitate command decisions by delivering intelligence through computer vision, pattern recognition, and algorithmic targeting.

In Al Toam and Rafah City along the Gaza Strip, precision strike has been utilised to target both essential and non-essential ‘military designated’ targets that, upon identification by AI computer vision and algorithms, have contributed to the 62,000 Palestinian deaths since August 2025. AI use by the IDF, however, is not a new concept. Its most prominent anti-air capability, the Iron Dome, utilises AI to disrupt missile threats, including those from Iran, in 2024 and 2025.

AI is not only reserved for strategic assets like anti-air capabilities, but has also integrated itself into the tactical decision-making processes of individual soldiers through AI-enabled scopes such as SMASH by Smartshooter.

Akin to an ‘auto-aim’ function in popular video games, the system utilises ubiquitous image processing algorithms to select targets and affords a more efficient engagement sequence to individual soldiers. This then feeds into a large database of pattern recognition and characteristics that are attributed to ‘typical belligerents’, including characteristics of uniform, combatant weapon systems, and even patrol formations.

Here lies our first problem: What does a combatant belligerent look like?

‘The Gospel’: The Hand of God

The IDF ‘Gospel’ system, designed to target infrastructure and buildings, is built on both historical databases of traditionally ‘Palestinian areas’ of cultural significance and militant locations within the Gaza Strip. Using software called ‘Alchemist’ to categorise and sort imagery and surveillance data, Alchemist distributes information to multiple intelligence and targeting departments of the Israeli Ministry of Defence. This data is fed through the ‘Fire Factory’ and disseminated to land, air, space, and joint commanders to decide on appropriate targets.

The Fire Factory categorises these targets into one of four types:

- Tactical targets: denoting armed militant cells, warehouses, launchers, and cell headquarters.

- Underground targets: ‘Hamas’ or ‘Jihad’ tunnels.

- Family Homes of ‘Hamas’ or ‘Jihad’ operatives.

- Power Targets: residential homes and other targets.

The Gospel consolidates these targets and offers potential ammunition types and collateral damage percentages to commanders for execution.

In essence, these targets have been rationalised to the international community as an opportunity to exert civil pressure on Hamas due to its militant cell structure. However, targeting exact locations of Hamas or Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) without targeting essential civilian infrastructure and culturally significant sites has become scrutinised by the international community.

The Gospel’s ability to categorise based on outdated and oftentimes inactionable intelligence, as well as biased cultural preconceptions, has highlighted both its innovation in doing so and the consequences of relegating ‘military necessity’ and ‘humanity’ LOAC considerations.

Here lies our second problem: when does military necessity outweigh humanity in the operational context?

‘Lavender’

Similarly, built upon large data models based on historical records and surveillance that combines facial recognition with the over 100 checkpoints currently operating in the Gaza Strip, 'Lavender' seeks to target specific militants or groups.

Lavender targets are engaged with 90% accuracy. However, context is vital to understanding why this system has garnered backlash from the international community.

First, you must understand that Hamas have and continue to exert enormous control over the Gaza Strip. This influence extends across all areas of governance and civil society, as well as essential occupations such as doctors, teachers, and the police force. As a result, IDF discriminate targeting platforms must contend with the intertwined nature of Gaza society with militant cells.

Lavender identifies ‘suitable’ targets, pairing specific people, groups and vehicles with their homes and frequented locations, including hospitals, markets and Mosques, subsequently recommending a weapon to analysts based on their rank and status. Unguided missiles are used to neutralise targets of a lower rank due to their mass production and relatively cheaper cost. Lavender’s output of a single potential high-value Hamas operative allowed for up to 100 civilians to be rendered as collateral damage.

Here lies our third problem: does a limit on ‘collateral damage’ exist if it achieves the mission?

The Human Approval

AI used within all major IDF AI initiatives depends upon the quality, validity, and understanding of the humans analysing and collecting the intelligence vital to the platform’s effective prosecution of targets. Both Gospel and Lavender require final human approval for execution; however, the inherent cultural and racial biases that underpin the conflict must be reflected upon to fully appreciate the system that is increasingly relied upon to enact a commander’s will.

Hamas attacks on the 7th of October 2023 enabled the IDF to enact air strikes to counter and disrupt land-based Hamas cells. This has culminated in the most recent May 2025 IDF offensive, Operation Gideon’s Chariot, which has seen the dramatic acceleration of AI-enabled kinetic strikes onto designated power targets.

Israeli intelligence analysts have and continue to legitimise their targeting references of likely civilian infrastructure and personnel through these historical arguments, and have, to an extent, encoded these biases into the systems designed to remain objective.

These biases manifest in various aspects of social, religious, and political life. The training datasets of military AI systems often misrepresent certain groups of people, environments, or behaviours. In the case of over-representation, male-specific characteristics regarding body shape, stature, and mannerisms may be equated to a universal representation of all people, both combatant and civilians.

Further to this, AI Decision Support Systems (AI-DSS) continue to adapt their data models based on intelligence reporting. However, where AI continues to enable command decision, that decision still sits with the human operator.

Herein lies our final problem: Does liability for targeting ever transfer from human operator to machine?

Australia’s Long-Range Strike

Australia’s contemporary air and missile defence architecture remains in a phase of modernisation, designed to provide both protection to deployed forces and layered defence of the continent. At the tactical level, the Army has transitioned from the legacy RBS-70 system to the National Advanced Surface-to-Air Missile System (NASAMS), delivered under LAND 19 Phase 7B. Operated by the 16th Regiment, Royal Australian Artillery, NASAMS batteries are mounted on Hawkei and HX77 platforms and integrate CEA Technologies’ active electronically scanned array radars alongside other sensors.

At the strategic level, the Jindalee Operational Radar Network (JORN) continues to provide long-range over-the-horizon detection, extending surveillance coverage up to 3,000 kilometres. JORN’s feed into the broader Integrated Air and Missile Defence (IAMD) framework underpins situational awareness across the approaches to northern Australia.

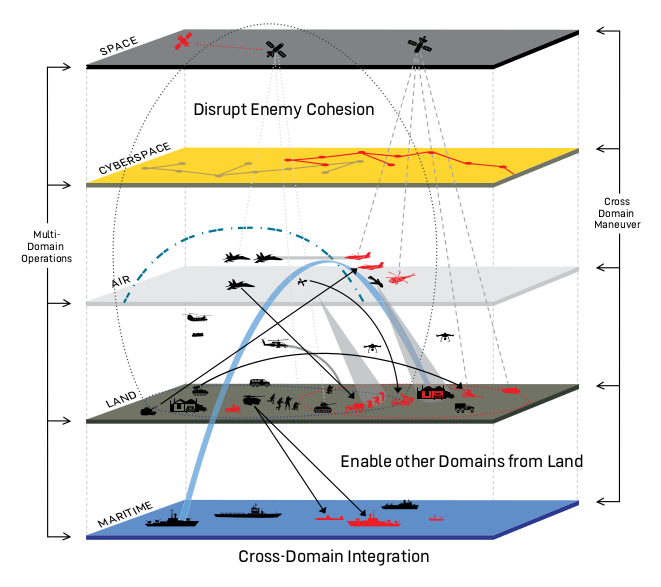

The effects of kinetic and non-kinetic targeting are compounded when conducted within a multi-domain operating environment (OE). Contemporary OE’s and the kinetic effects prosecuted within them rely upon the efforts of a joint intelligence, surveillance, and target acquisition (ISTAR) system. This system is a synchronised and orchestrated platform which involves capabilities at the tactical, operational, and strategic levels of command.

Targeting intelligence processes within the Royal Australian Air Force further complements these ground-based systems. The F-35A Lightning II, with its advanced sensor fusion and data-linking capabilities, provides critical real-time ISTAR, feeding into joint targeting cycles. This is coupled with the acquisition of advanced munitions such as the AARGM-ER anti-radiation missile, enhancing the suppression of enemy air defences, and the AGM-158C Long-Range Anti-Ship Missile (LRASM), which extends strike reach against maritime targets. The Royal Australian Navy complements this posture with the fielding of the SM-6 long-range interceptor aboard Hobart-class destroyers, offering fleet-wide air and missile defence.

These capabilities are tested and refined through multinational exercises such as Talisman Sabre 2025, where NASAMS and HIMARS were integrated into high-tempo joint operations. Exercises in which opportunities to utilise a unified, joint command system enable the ADF’s forward movement toward a layered and interoperable targeting architecture capable of countering sophisticated air and missile threats in concert with allies.

In Conclusion

Collectively, these developments demonstrate that Australia’s surface-to-air and targeting systems are both nascent and rapidly advancing. While they provide growing precision and reach, the doctrinal challenge lies in integrating these platforms within an ethical targeting framework that retains compliance with the LOAC. In this sense, they serve as the foundation upon which any future integration of AI in targeting must be carefully layered.

While the IDF’s use of systems such as Gospel and Lavender illustrates the speed and scale benefits of AI-enabled target generation, academic analyses stress that these remain decision-support systems, not autonomous weapons. Their legality and morality depend entirely on how commanders employ them within the LOAC, and whether safeguards mitigate the risks of automation bias, data error, and systemic civilian harm.

The ADF may face similar ethical challenges as previously mentioned. Primarily, to leverage AI’s usefulness in speeding up targeting acquisition while maintaining its reputation for ethical conduct in future conflicts. Where the IDF has received international criticism for excessive civilian harm, Australia must show that AI-enabled systems can be employed to enhance, rather than undermine, compliance with the LOAC. This approach ensures that human-machine teaming becomes a force multiplier that is effective in operations, legally compliant, and ethically justifiable within Australia’s strategic framework.