We’re all talking authentic leadership and how important it now is.

I’ve known this for a while, but it was brought home to me suddenly last week. A young friend of mine had a career defining interview, this was a role she wanted badly, a pivotal promotion in her organisation. As the interview progressed, she talked openly about her upbringing, cultural prejudice, depression, growth, shame, overcoming doubt, progress – not topics she was planned to explore but where the interview went.

Assessment: ‘Not Ready’.

For my generation, the 50-year-old largely Caucasians in our Army, I’d argue we have an inbuilt suspicion of authenticity. We like the idea, but only if it empowers the individual and the team. Too much authenticity is a problem for us. It distracts and disables. The right amount is a genuine enabler but too much and it becomes a blocker to mission success.

This paper will argue that Army’s attitude to authenticity presents a clear and present risk to attracting and retaining today’s talent in our institution. Young Australians are far more comfortable, far earlier in their career to adopt authentic leadership traits, but our systems reject them when encountered. These traits, whilst confronting to ‘we in our 50s’, in fact need to be honoured and encouraged, not red flagged.

The Old Model of Authentic Leadership

Let’s be honest, authentic leadership might be a new title but it’s an old idea. Who reading this blog doesn’t think they have incorporated the idea of being authentic into their work, family, education and spiritual development? Of course you have.

But let’s remember how we came to adopt these authentic traits.

First, we learned how to fake it. In the absence of any first-hand knowledge of your new organisation, your team, your Army – your first instinct was to fit it. It makes sense. Do what others do, wear what they wear, behave as they do – figure out the rules and norms of your new organisation and try to do so without stuffing up too badly. Calling it ‘fake’ isn’t really doing it justice I know. A better way might be to describe this phase of your career as ‘learning’. You were adopting the behaviours of an officer, an NCO where you were inculcating the values of Armoured Corps, or logistics - you were ‘becoming’ a member of the ADF. You engage with that process of growth authentically, I think that’s true for most of us, but it’s hard to say – early in your career – that you were being your authentic self. The process of becoming is an assimilation, forces from outside of you and within you are churning to figure out what type of soldier you will be, what matters to you, how you interpret rules, how you exhibit and model military behaviours. Each of us travel that path differently and arrive at different conclusions, different points of emphasis, as we frame our personal ‘leadership style’. But I would argue at some point in your career you felt educated, informed, experienced and confident enough to say, ‘this is my leadership style’. It’s a style I understand, which has comparative strengths and weaknesses and one that is different to those around me. It is an authentic expression of me. When I employ this style, I bring my whole self to the role.

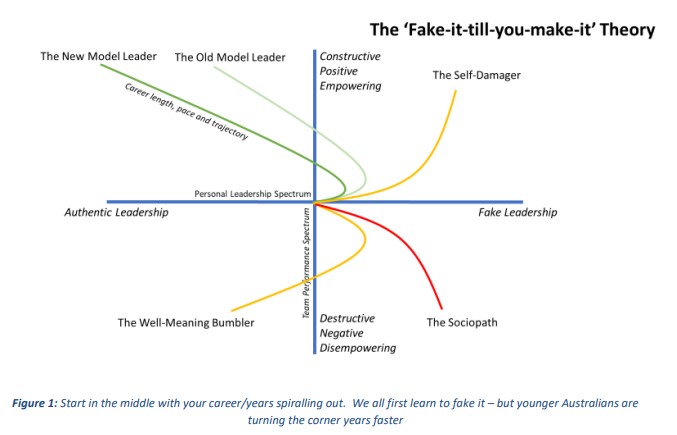

The Old Model is the path I walked, perhaps you feel the same way. Starting at the centre of Figure 1 above, maybe you can recall when you ‘crossed the divide’ (where the green lines cross the Y Axis) and felt comfortable to express an informed opinion on your personal leadership style, when you had reflected sufficiently on all those elements of leadership, all those theories, and had come up with ‘your take’. For me, I think ACSC was a key moment, where I put pen-to-paper and mapped out my thinking. Early thirties.

The New Model of Authentic Leadership

The New Model I’m proposing is in play for our more junior colleagues and follows roughly the same path, but at increasing speed, and with an ‘even more authentic destination’ than we that are older. Where I started building confidence in my own thinking, our junior officers and soldiers (maybe we can call them Generation Y and Z) are racing along that pathway much faster (the dark green v the light green line).

They have reflected more deeply, spoken more openly, shared more completely than we in Generation X or Boomers. What’s the evidence? Well, all I have are anecdotes. But if anecdote is the germ of science, I’m sharing them now to encourage the conversation and debate:

- I see Army reject/postpone recruit applicants when they reveal physical or mental injuries at initial interview (older generations learned not to reveal such weakness)

- I see Army reject/postpone in service officers experiencing PTSD or mental health episodes due to our sense of organisational risk (older generations learned to never reveal such thoughts)

- We exit/refuse re-entry to Army capable soldiers for not having exactly the right qualification or experience in their returning trade (older generations learned once out to ‘never go back’)

What I’m suggesting here is that we have built an Army that relies on its individuals employing the Old Model of Authentic Leadership to succeed and progress. Fake it until you make it far enough into our system, and only then, safely reveal your true self. If you approach our institution with naïve reveals and open acknowledgements you run the high risk of our systems flagging you, blocking you, exiting you.

What about the Yellow and Red Lines?

Figure 1 is principally about discussing the different speed and trajectory between the two green lines. But I suspect many of you reading this are equally interested in the yellow and red lines – so let’s discuss them quickly.

In practice we all know of leaders who better fit into the other three quadrants, which I’ll summarise here, but not formally explore.

- The Self-Damager. This is the leader who learned to fake it so well that either they or their team never let them evolve into a more authentic style. I fear this is a pretty common destination for Army Leaders. We learn to ‘put on the mask of command’ but never cross the divide to understanding that it should only have ever been temporary. The damage occurs when your life is one of ‘constant switching’ from officer to husband, then to school mate, then to sibling, then to sports coach, then back to spouse. At 45 years you’re anxious, short-tempered and unsure of ‘who you really are’.

- The Well-Meaning Bumbler. Authenticity does not automatically lead to improved team function. Without conjuring up images of Ricky Gervais in The Office, most of us will know of leaders who over-share, over-care or otherwise allow their need to let themselves and others self-actualise to the point where team function and effectiveness suffers.

- The Sociopath. All fans of Jon Ronson’s book ‘The Psychopath Test’ will note my simplistic equation is not accurate. A non-authentic leader + disempowered team ≠ sociopath. There is a far more complex diagnosis required here – but my simple point is that there exists in our Army an inverse to authentic empowering leadership. That inverse goes out of its way to undermine, to delude and to ruin – usually as a method to grow the leader’s reputation or career. Terrifying for an organisation when encountered – because they are so often initially very well regarded, seen as hard-working, effective leaders. Their trail of destruction quietly overlooked.

This is an interesting (and not fully developed) aside. Our key issue is what to do with the vast bulk of our new leaders who have accelerated to a ‘level of authenticity’ their seniors now struggle to comprehend. For those senior leaders, its time.

Time to take a risk

In addressing a perceived near-term risk of an individual not being fit enough, resilient enough, flexible enough to make it in our Army, we have (inadvertently) created a larger system risk that our target population of young, diverse Australians are no longer able to join us, grow and stay.

What needs to change in your Authentic Leadership approach? We all need to more open to conversations with recruits, new and returning people that reveal far more than we traditionally felt comfortable with. And we need to more ready to accept the entire person into our team. Perhaps oddly, this is really a challenge on you – the more senior leader – to be more resilient. When you encounter what you assume to be frailty, why not pause, reflect and re-invest in that individual, rather than walk away.

Remember, the New Model isn’t saying our younger generations have new/additional risks – it’s only saying they are quicker to reveal them than we who grew up with the Old Model were. We all suffer from the same quantum of injuries, depressive episodes, maladies and complexities – but Gen X learned to keep it to themselves! This new generation have learned its ok to share, and that the act of sharing won’t be held against them. For we that are old, this is a new rule.

This is an insightful article written with much frankness and humility. I have used it for my digital communication analysis assignment. I have only two points of possible improvement to offer:

1. The X-Y plot graph should appear bigger or have the ability to expand by clicking.

2. Key messages in the article could be highlighted using a larger font in a different colour (like in The Economist). This would capture readers who skim-read your article.

Kind regards,

Jonathan