There has been much discussion over the need to be ready for an alarming number of emerging threats posed by new domains, technologies and the speeds of event changing the character of war at an accelerated rate. Much of this is captured by Army’s new adoption of the Decisive Action Training Environment (DATE) adversary framework. However, exactly what these threats are remains vague. This is likely because joint land combat is not expected to be declared, but instead may erupt rapidly from our adversary’s extensive use of coercive diplomacy and competitive political, economic, informational, humanitarian and unconventional forces employed in non-attributable ways. These ambiguous methods are encapsulated by the elusive term ‘hybrid warfare’; a broad concept that warrants detailed exploration if it is be of any use to the tactical practitioner. Global conflicts have proven how devastating ‘hybrid’ tactics can be against even the most powerful and professional militaries. Reading doctrine, developing a broad awareness of trends, and possessing a general desire to be ‘ready’ for emerging adversary tactics is not enough. We are now challenged with how we might replicate this in our live training so that our strategic observations may translate to readiness at the soldier level.

EX TALISMAN SABRE 19

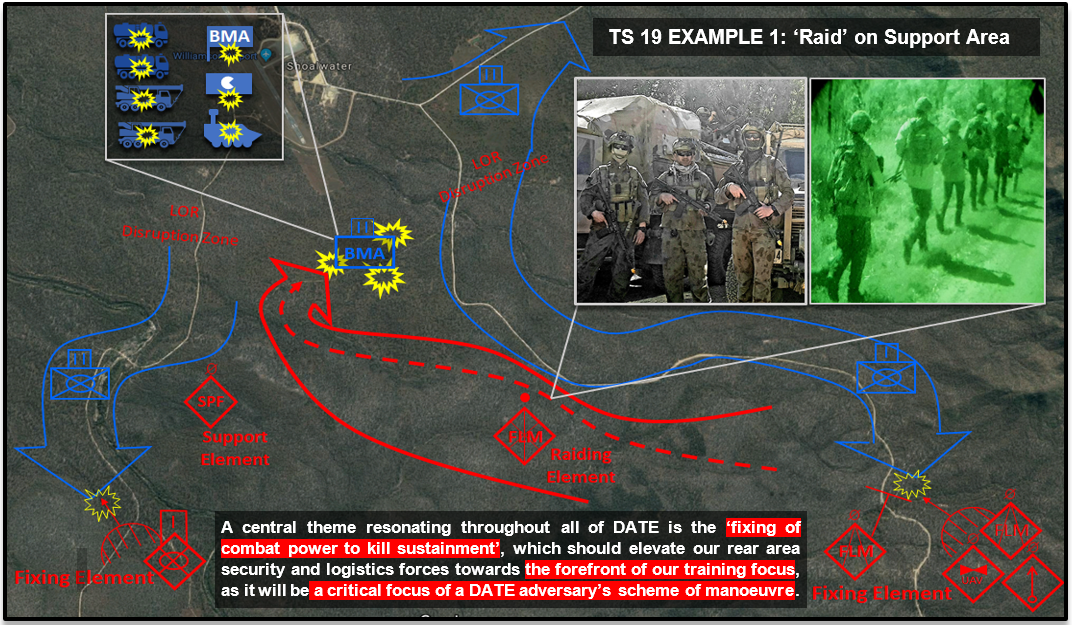

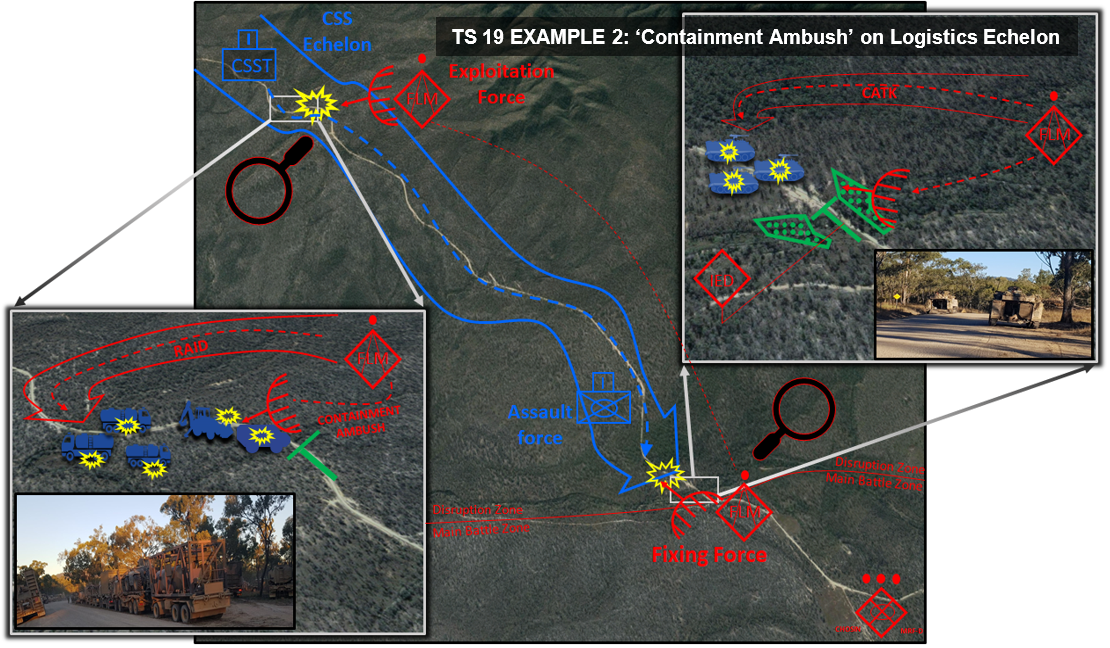

Over the course of Exercise Talisman Sabre 19 (Ex TS 19), the Combat Training Centre’s (CTC's) Conventional Operating Environment Force (COEFOR) PL joined the 7th Australian Brigade’s ‘Kamarian’ Brigade Tactical Group in representing a DATE hybrid adversary to support the 1st Australian Brigade’s training scenario. The COEFOR PL is CTC’s dedicated enemy force comprised of selected members from RAINF, RAE and RAA. For Ex TS 19 it formed the ‘Free Legais Militia’ along with soldiers from the Royal Military College - Duntroon's training support platoon, Special Operations Command, Information Operations specialists, and Explosive Ordinance Disposal personal, all combined under command of the 7th Brigade.

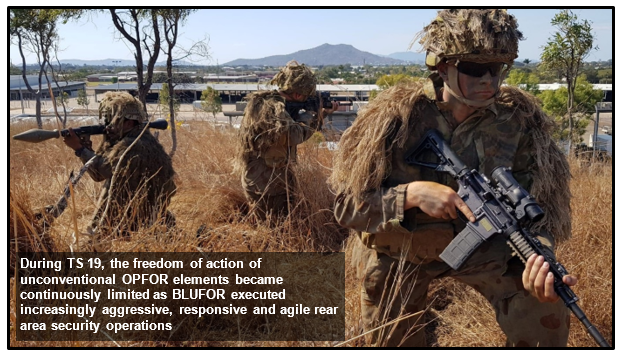

This enemy force leveraged time-proven clandestine and covert tactics, such as unconventional and criminal methods, to screen, block, raid and ambush key friendly force systems and vulnerable high value equipment and troop concentrations. The cumulative degradation caused by these elusive groups supported the greater 7th Brigade plan to strike key assets and inflict delay whilst avoiding exposure of the preponderance of the enemy's main body to avoid destruction. Unconventional elements, such as COEFOR PL, fit accurately within the DATE adversary framework as Individual Mission Detachments tasked to conduct Disruption or Exploitation tasks ahead of, or alongside, stronger conventional Battalion Tactical Groups operating in the Main Battle Zones. It is no new thing to observe that the ‘continental’ schools of thought on which our tactics are based, with strict hierarchical structures and prescribed planning processes, at times leave us ill-equipped to comprehend, and thus combat, unconventional adversaries[1]. In our efforts to fully incorporate DATE across Army, we should understand that whilst ‘hybrid warfare’ is not new, it departs in key ways from previous ‘linear’ opposing force doctrine (which in the Australia Army was based on the fictional Musourian Armed Forces) in its incorporation of more potent and complex elements from both past and present warfare.

The Past

The primary colours are only five in number but their combinations are so infinite that one cannot visualise it…in battle there are only the normal and extraordinary forces, but their combinations are limitless; none can comprehend them all. – Sun Tzu [2]

As far back as the Peloponnesian War and the writings of Sun Tzu in 5th century BC, irregular fighters have proved the bane of numerous conventional militaries, having a significant impact on the broader conventional campaigns they were a part. Finnish snow infantry during the 1939 Winter War, lacking anti-armour weapons, instead utilised felled trees, ditches, boulders, small arms, IEDs and winter itself to halt entire Soviet armoured divisions, killing over 200,000 in just 3 months[3]. Viet Cong (VC) guerrillas during the Vietnam War delivered a decisive blow right into the heart of United States’ Centre of Gravity when the effects of their 1968 Tet Offensive morally dislocated the American people’s perceptions of success, trust in their leadership and their will to endure[4]. Chechen separatist fighters defending Grozny from Russian invasion were able to attrit 789 Russian infantry in the opening 60 hours of barbaric urban combat, including the destruction of 20 out of 26 Russian tanks, and 102 of 120 Russian BMPs[5]. In the 2006 Lebanon War, Israel, the premiere military power in the Middle East, was shocked after it suffered repeated tactical defeats inflicted by Hezbollah militia fighters equipped with IEDs and AT-14 Kornet ATGMs, despite the overwhelming advantages of their most advanced Merkava battle tanks, fire support and ISR [6]. Even the Australian Army's operations in Afghanistan and Iraq have highlighted the difficulty of defeating determined irregular fighters, who have often outpaced us in their improvisation of cost-effective weapons, and pioneering methods to manipulate the internet, social media and news to multiply the effects of their combat successes.

The use of irregular, unlawful, uncivilised and even barbaric methods of fighting, including murder, looting, pillage, kidnap and extortion, are older, darker and more widespread forms of war which have prevailed for the longest periods of human history and are an anathema to stronger conventional forces. Unsurprisingly these tactics have even been turned by civilised states for their own use at times through the common practice of recruiting irregular practitioners as uniquely skilled warriors, light cavalry and infantrymen to patrol, reconnoitre and skirmish; the Auxilia of the Roman Legion’s, 16th century Hussars, 17th century Bashi-Bazouk, and 18th century Cossacks, Highlanders and Borderers are but some examples. In the past ‘the officers of 18th century civilised states averted their gaze knowing that the well-drilled armies of the Clausewitzian kin would scarcely have been able to operate’ without these more unlawful warriors, as noted by John Keegan[7]. Western military doctrines, which optimise the use of paid and disciplined forces by professional bureaucratic militaries, still remain susceptible to irregular fighters who readily exploit our prevailing codes of ethics, diplomacy, legality and structured conceptions of tactics. Recognition of the way these irregular ‘hybrid’ forces have influenced large conventional operations in the past frames our appreciation for their enduring effectiveness in today’s conflicts and future training.

The Present

‘Regular, irregular, terrorist, and criminal groups who decentralize and syndicate against us and who possess capabilities previously monopolized by nation states… it is for these threats we must prepare’ - General George Casey [8]

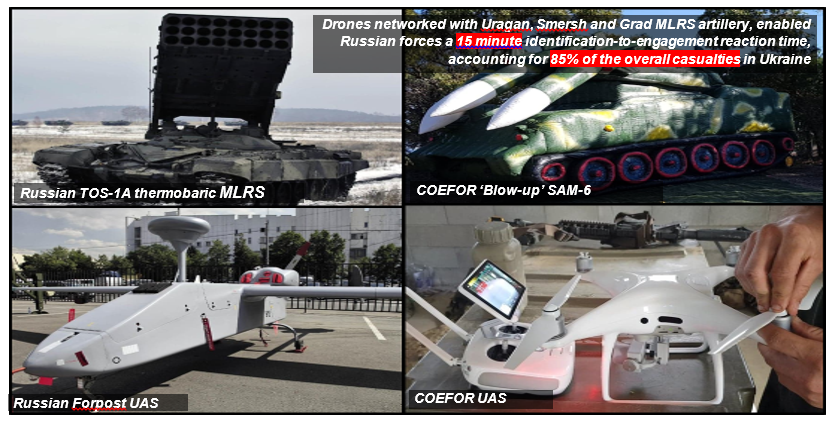

In 2014, four years after the original release of many of the current DATE publications, their relevance was confirmed after hybrid-style tactics were powerfully demonstrated during the Russia-Ukraine War. As the only true state-to-state war between European nations since the 1991 Balkan Wars, Russia’s operations against Ukraine conveyed timely lessons. Many noted the stunning future-proof design of the T-723B/T-90 MBTs; that bold offensive action by armoured forces was irrelevant without sufficient infantry to hold captured gains; the enduring survivability of dug in infantry to massed artillery; and that Artillery with improved propellants, burst-techniques and sub-munitions, now supplemented with EW and medium range target acquisition drones, was still the chief cause of battlefield casualties [9]. But the true exception was Russia’s employment of new tactics from which parallels to DATE ‘hybrid warfare’ can be drawn. Whilst hybrid warfare is a concept that defies template, the Russo-Ukraine conflict provides Army’s junior leaders with three precise examples of how it may manifest itself at the tactical level; being information operations, cyber warfare, and use of unconventional forces.

Information operations

‘The first rule of unrestricted warfare is that there are no rules’ – Colonel Qiao Liang[10]

Firstly, Russia’s military deployment to Ukraine was synchronised with equally important information shaping operations. Russia’s secretive sponsorship of anti-government protest groups within Ukraine were designed to stir violent civil unrest in response to the ousting of Pro-Russian President Yunakovych in 2014. This man-made national crisis was deliberately mis-characterised as an internal uprising against the new Ukrainian government’s ‘fascist junta’. High quality Russian sponsored fake news media produced an ‘information blitzkrieg’ effect, portraying to the world a convincing alternate reality of events that manufactured a pretence for foreign ‘assistance’ by the Russian Ministry of Emergency Situations. This narrative was used to conceal Russia’s joint force entry operations into Ukraine in order to destabilise its growing relations with the EU/NATO alliance [11]. Russian information operations were so effective that they enabled the invasion of Ukraine to take place whilst keeping foreign perceptions of its actions below the threshold that would have invited extra-regional forces to intervene in Ukraine’s defence.

Cyber warfare

Secondly, Russian cyber warfare, also classed as a form of Information Operations under DATE doctrine, was used to neutralise Ukrainian technological overmatch. Civil instability was synchronised with Russian denial of service hacking attacks which targeted the Ukrainian government’s computer network to collapse it from within. Additionally, secret deployment of BTR mounted Borisoglebsk 2, and Truck mounted Zhitel, Kvant Avtobaza, Leer and Krasukha-2/4 systems, were used to locate, intercept, jam and deceive Ukrainian broadband cellular, GPS, ground and aerial communications, which were subsequently targeted by massed concentrations of artillery [12]. At Zelenopillya, the Russian artillery supporting proxy separatist militia fighters was able to destroy two Ukrainian mechanised battalions in less than 3 minutes utilising MLRSs firing airburst thermobaric warheads - a demonstration of cyber warfare being intrinsically linked to the delivery of lethal effects [13].

Unconventional forces

Perhaps the most arresting example of hybrid warfare was the employment of unconventional forces. On 24 Feb 14, military forces without insignia, but boasting suspiciously advanced weapons, surrounded all major Ukrainian military bases in the strategically vital Crimean Peninsula. Through the threat of force these elements secured the surrender of Crimea in 20 days, resulting in only 2 casualties. These men were in fact thousands of ‘volunteers’ assembled by Russian FSB and GRU handlers; hardened criminals, mercenaries, government defectors, and thuggish looters formed into ‘local self-defence’ militia groups and backed by teams of Russian Special Forces in disguise.

Russia’s stunning seizure of the Crimean Peninsula, which based up to 22,000 Ukrainian military personnel, and critical access to the Baltic Sea, was shortly followed by similar ‘civil uprisings’ against the Ukrainian government forces by Russian-backed separatists in the Donbas and Donetsk, regions even deeper within Ukraine[14]. As Ukrainian defences consolidated, the conflict transitioned from an insurgency to large scale conventional war. Russian-backed militia fighters were directly reinforced by conventional Tank, Artillery, EW and Engineer heavy Russian Battalion Tactical Groups. Though the war remains an undecided stalemate, these hybrid forces still exist today in consolidated ‘Peoples Militia’ Brigades, with the ability to deploy tens of thousands of former separatist fighters with Russian fire support[15].

Defining Hybrid Threats

‘When the enemy advances, we retreat. When he escapes, we harass. When he retreats, we pursue. When he is tired, we attack… when he pursues we hide, when he retreats, we return.’ – Mao Zedong[16]

With the example above as a model, the DATE hybrid threat is seen to depart from previous adversary doctrine in its incorporation of ‘Regular-Irregular Synergy’. The basic definition outlined in TCN 7-100 DATE ‘Hybrid Threat’ provides the premise: a diverse and dynamic combination of regular forces, irregular forces, and/or criminal elements all unified to achieve mutually benefiting effects [17]. More explicitly, hybrid warfare sees unconventional forces as a critical component, and not just secondary to, the campaigns conducted by conventional forces. Irregular forces reap the benefits of their conventional ally’s ISR, logistics, firepower and operational pressure forcing the opposition to operate in a consolidated manner. In return, conventional adversaries receive unconventional support in killing sustainment, negating technological overmatch and controlling tempo. The introduction of infinite variations of corrupt, criminal, insurgent and guerrilla groups alongside a conventional adversary allows us to acknowledge the Diaspora of deeper social, political, economic and information motivations that define a realistic and changing operating environment in our training.

Increasing our incorporation of DATE adversaries into our training will allow us to train for an opponent that possesses a diverse mix of threat groups with the ability to scale their strategy to change the character of a conflict. The same tactic of symbiotically mixing such diverse groups can be seen in Alexander the Great’s Macedonians, the Roman Legions, Mongol Hordes, Napoleonic Corps, German Panzer Divisions, and even current-day Brigade Task Forces [18]. As TC 7-100-2 DATE Opposing Force Tactics outlines, ‘Regional’ strategies emphasise overmatch via conventional battle, ‘Adaptive’ strategies leverage asymmetric defence and economy of force tactics, and ‘Transitional’ strategies bridge the two when a more powerful extra-regional opponent enters or withdraws from the campaign[19]. For example a ‘Regional’ strategy of conventional overmatch was utilised by the Russians against Ukraine in 2014. Alternatively a more defensive ‘Adaptive’ strategy was adopted by North Vietnam during its transition to an insurgency against more conventionally powerful US forces supporting South Vietnam from 1964. The VC utilised a method called ‘One Slow, Four Quick’ to initiate the majority of combat actions, leveraging maximum surprise and tempo to defeat the US’s overmatch in offensive manoeuvre, shock action and firepower. A typical operation would consist of a dispersed infiltration, then a sudden concentration for a massed attack followed by a swift withdrawal to draw defenders into well-prepared ambushes. Often the VC were able to devastate their conventionally superior Western adversaries without actually ‘meeting’ them, ‘subduing their enemy without fighting them’ as Sun Tzu alluded long ago [20]. These are real world examples of the functional tactics outlined within TCN 7-100. Whilst hybrid adversaries now incorporate new advantages in organisational complexity to change the character of conflicts, these advantages can be dislocated through targeting of the adversary’s strategy.

Defeating Hybrid Threats

‘Now the troops of those adept in war are used like the ‘Simultaneously Responding’ snake of Mount Ch’ang. When struck on the head its tail attacks; when struck on the tail, its head attacks, when struck in the centre both head and tail attack – Sun Tzu [21]

Hybrid tactics do not just emerge; they serve specific ‘Regional’, ‘Transitional’ and ‘Adaptive’ strategies, all of which can be isolated and dislocated. In Vietnam, US forces learned to refuse attacking VC positions head-on and implemented ‘semi-guerrilla’ jungle-swamp raid, ambush, booby trap, and recon techniques to combat the NVA’s ‘Adaptive’ strategy. Using their superior mobility and firepower, they pioneered tactics such as mobile fire-basing, air assault, and area ambushes to draw the VC into ‘sacks’ for their destruction in detail; learning how to ‘Out G the G’ [22]. A more modern example of this can be seen in the infamous Find, Fix, Finish, Analyse, Exploit, Disseminate (F3EAD) targeting cycle utilised to degrade the brutal Al-Qaida in Iraq (AQI) insurgency in 2009. Only after heavy losses did the US learn to adapt by eliminating enough of its institutional boundaries to forge its military and inter-agency forces together into an relentless intelligence-fused hunting ‘network’, targeting AQI’s ‘Adaptive’ strategy directly[23].

In 2012, AQI’s offshoot organisation, ISIS, after shattering the moral cohesion of Iraq’s Coalition-trained security forces, would establish massive semi-conventional Motorised Infantry, Armoured and Support Corps in their shift to an offensive ‘Transitional Strategy’ to secure a ‘Caliphate’. Their highly coordinated phased campaign of surprise IED ambushing, artillery, urban assault, and small-unit armour and infantry manoeuvre re-used the Western ‘clear-hold-build’ model to seize successive cities. ISIS were able to overcome Syrian forces at Tabqa, Menagh, Deir-Ez-Zor, and Palmyra and Iraqi forces in Mosul, Tikrit, and Ramadi [24]. It took four years for Iraqi, Kurdish, Lebanese and Syrian forces, with training, advice and fire support from international coalitions including the US and Australia, to encircle and commit ISIS forces to close combat. There they adapted to new realities, such as the impossibility of isolating a modern city, the immediate loss of initiative that occurs upon entering a city in the assault, and that operational reach is only proportional to population support [25]. As at the time of writing, ISIS has been degraded to a mere 1% of its former territory[26].

Even Ukraine, after recovering from the salutary shock of Russia’s invasion, redeployed 16 newly modernised Infantry, Tank, Artillery and Aviation Brigades alongside its hybrid militia forces to overcome Russia’s ‘Regional’ strategy of political intimidation. The anti-Kyiv militias were found to lack the necessary C2, logistic support and combat power needed to hold terrain, both as a consequence of poor discipline and the need for Russia to maintain its deniability. Currently Russia remains fixed within a quagmire of its war-ravaged ruins, unable to advance further against a resurgent wave of Ukrainian nationalism. International confidence in Russian-backed media has disintegrated, and it is forced to subsidise its devastated captured territories to an estimated cost of $3 billion a year[27]. Hybrid threat solutions cannot be templated, but notable successes have already been achieved globally by forces who adapted their tactics to target the hybrid adversary’s core strategy.

Australia’s Hybrid Threat

Tactics that do not serve strategy are wasteful at best, and counterproductive at worst – B. A. Friedman[28]

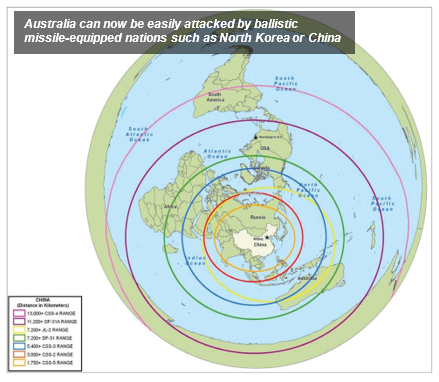

It is clear to see how Hybrid Warfare will be relevant to our current strategic reorientation as the global power balance rapidly shifts from the unipolar dominance of the US to a multipolar order of emerging powers. Russia's ‘New Generation Warfare’ has displayed impressive capabilities for de-stabilisation, be it in Ukraine, US election meddling or hyper-sonic missile technology. Great power competition has returned as the US-China Trade War destabilises global economies and Global Defence spending increases[29]. Australia has dropped from being the second largest economy in all of Asia in 1980, to now the equivalent of a mere 5% of China’s, and predicted to rank well behind most major South East Asian countries, including Indonesia’s, by 2050 [30]. To date Army’s cultural identity as a middle-weight expeditionary force specialising in small unit tactical excellence has remained reliant on strong alliance frameworks alongside the UK and US. With US dominance in Asia predicted to gradually recede, the unrivalled conventional dominance we have enjoyed for so many years may diminish, and our strategic isolation from our traditional allies may increase.

The most recent examples of hybrid warfare can be seen in China’s philosophy of warfare. China’s trajectory towards achieving leading global power status by 2050 has been accompanied by its aggressive territorial posture at sea and global ‘soft power’ engagement. Its ‘Ring of Pearls’ and ‘Belt and Road’ strategies are backed by rapid military growth and economic dominance. It is inappropriate to posture fatalistically about war with China or any other nation, but China’s interests are extending to its attempts to supplant Australia as the dominant economic and security partner of choice in our immediate region: the South Pacific. Consequently our ‘Pivot to the Pacific’ has seen our Defence strategy return to one of denial of external influence in our near region, similar to our historical defences against Germany, Japan, and the Soviet Union, or in addressing instability in East Timor, the Soloman Islands and Bogainville [31]. Both China’s ‘National Military Strategic Guidelines in the New Period’ and its famous 1999 military publication ‘Unrestricted Warfare’ call for use of asymmetric tactics where ‘nothing is forbidden’ [32].

As an example, tactics used in Ukraine such as computer hacking, subversion of global banking systems, currency manipulation, media disinformation, territorial coercion, foreign espionage and ‘Legal Warfare’ and loan-trapping are hybrid tactics already in use by China globally [33]. These actions reflect an understanding of the weaknesses of the societies, and by extension the militaries, of Western nations such as Australia’s, which are highly reliant on technology, resources and information. In Septemeber 2019, ASIO Chief Duncan Lewis, warned that Australia’s greatest existential threat today is not terrorism, but the growing every day interference of foreign espionage efforts against Australia[34]. Australia’s reinforcement of its historical position as the economic, governance and security leader to our closest neighbours, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Fiji, Tonga and Samoa, is being matched by our unprecedented strengthening of our defence capabilities. If the aim of Australia’s new ‘Pacific Pivot’ is to maintain stability and deter potential threats in our near region, it is fitting then to assume that Army’s role is to train its forces to such an extent that our adversaries are convinced that they are likely to be tactically defeated if they choose to employ hybrid tactics against us. Exercises such as Hamel and Talisman Sabre are ideal opportunities for the Army to continue achieving this emerging strategic role, at the soldier-level upward, and in an alliance setting.

Conclusion

The potency that hybrid tactic’s have had globally, and on exercises such as Ex TS 19, indicate that there is a great myth that exists among many Western military thinkers who believe that by mastering the challenge of the 'worst case scenario' – that is all-out full scale conventional warfare with a peer enemy – we will then be able to manage the ‘lesser’ tasks of small scale, asymmetric and unconventional conflicts. This claim is false. Each type of military operation, be it conventional war, counter-insurgency or HADR, needs to be treated as its own worst case scenario, with its own independent potential to bankrupt, exhaust or militarily defeat a nation's will to fight. The changing global power balance may increasingly force Australia into conflicts we would normally have deemed too ambiguous, competitive or ‘dirty’, and with potentially less international support than we have grown accustomed to.

Whilst DATE hybrid tactics are not new, their techniques and modes of employment are. This is something that can be incorporated into training, from Sect through to Coy level now, and up to Brigade level training as demonstrated by the 7th Brigade on Ex TS 19. Too often it is tempting to ignore this reality in our training for the sake of ease and simplicity, and our soldiers and junior commanders are left with a frustrating incoherence between the ‘watered down’ enemy we sometimes train against, and the potential adversaries that currently exist in the world. If ignored, we could end up possesses the most potent Army in Oceania without a single enemy against which it will be suitable to fight. Historically Australia has not been good at preparing for its next war, and often future wars take on a character that is different to what we envisaged in our training. However, what is certain is that Army will deploy again, and when it does it will have to engage in violent, callous and unforgiving close-combat against forces employing a mixture of high-tech, or more enduring low-tech methods, in ways that render our perceived strengths irrelevant. CTC and its COEFOR PL are organisations that are dedicated to supplementing Army’s Battlegroups and Combat Brigades to replicate the contemporary operating environment by providing the wicked hybrid dilemmas necessary to facilitate honest and unemotional self-assessment of our own capabilities. Victory will go to the Army whose junior leaders test their doctrine against lethal enemy tactics, adapt creatively, and at a faster rate than their adversary.

Dyan.