As night began to fall on the 30th of November 1917 in Western Belgium, Australian soldiers of the 39th Battalion waited anxiously in an assembly point in no man’s land armed with nothing but their Lee Enfield rifles and helmets. The Germans ‘stood to’ in their trenches ready to receive some kind of attack, even if they were not yet aware of what this would look like. However, little did the Germans know that in less than seven hours, Australian soldiers of the 40th Battalion would be waiting in the exact same place, with the exact same equipment, ready to conduct the exact same raid. This is the story of one of the most well-planned and successful Australian trench raids of the First World War – the forgotten double raid of Warneton.

After months of bitter fighting in the area, Lieutenant Colonel Lord of the 40th Battalion conceived one simple idea: repeating the exact same raid one after the other. The target of the operation was a short stretch of trench west of the village of Warneton. The trench lay immediately north of the railway linking Warneton to La Basse Ville.[1] Warneton was a difficult target for the Allies (protected by the River Lys to the west and north), and it remained under German control throughout 1917.[2]

Scheme of Manoeuvre

Through the years of the war, it was learnt that time spent in extensive planning and preparation is not wasted. The preliminary phase of the raids started on 14 November 1917 with the 40th Battalion being allocated to the sector in front of Warneton, from the River Douve to the railway. From occupation, detailed reconnaissance ahead of the raid soon began with effort focussed on the identification of defensive locations, routines, the extent of obstacles, and possible routes across ‘no man’s land’. The Warneton Track was also constructed the night before the raid providing raiding parties a quick and defined withdrawal route.[3]

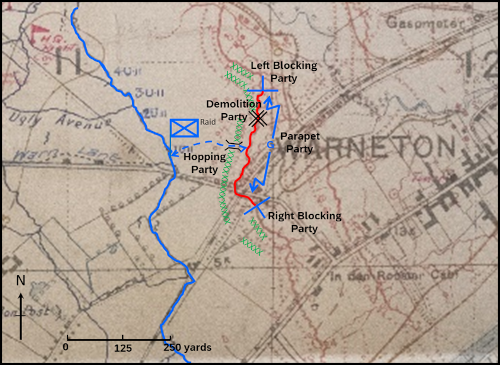

Raiding parties consisted of approximately 70 men who undertook nine days of dedicated training ahead of the raid. Both the 39th and 40th Battalion raiding parties were broken up into left and right assault, hopping, demolition, and parapet parties. The number of personnel in each party, led by a non-commissioned officer (NCO) or junior officer, varied slightly but each included soldiers allocated to specialised roles of scouts, bayonet men, thrower/bombers, signallers, runners, and stretcher bearers.

Their roles within the raids and the scheme of manoeuvre were well practiced. The raiding parties from both battalions were allotted much needed rest on 30 November 1917, the day immediately preceding the operation.

Everything was well planned and well thought through. The timings for the many different moving parts were well established but more importantly, critically followed. The 39th Battalion’s raiding parties’ ZERO hour was 1715 on 30 November 1917 – shortly after last light, and the 40th Battalion’s ZERO hour was still in darkness – seven hours later at 0115 on 01 December 1917. Timings relative to ZERO hour are shown in Table 1 to create a better picture of this.

| Timing | Description |

| ZERO -10 min | Raiding parties entered no man’s land and reached the assembly point clear of Allie wire. |

| ZERO | The artillery barrage began on the front line of enemy trenches as the assaulting parties moved from their assembly areas. Mortars were used for obscuration of the battlefield and counter-battery fire also commenced on targets in-depth. |

| ZERO +3 min | The artillery lifted and the raiding parties rushed forward through gaps cut in the wire. The raid was conducted supported by machine gun fire. Artillery was shifted to form a box 100 yards on the flanks and 200 yards in the rear of the objective. |

| ZERO +23 min | The withdrawal of troops began on order by the OC of the parapet party and was echoed by all those who could hear. |

| ZERO +30 min | Mortar smoke screen and machine gun fire lifted. |

| ZERO +40 min | The artillery barrage began to slacken. |

| ZERO +45 min | The main artillery barrage ceased. |

| ZERO +50min | The counter-battery barrage ceased. |

Table 1: Timings for each of the raids relative to ZERO hour.

The raids proceeded like clockwork, a textbook infantry attack. An artillery barrage, followed by the rushing forward of raiding parties through pre-determined routes under the cover of machine gun fire, followed by a withdrawal and reorganisation.

Raiding parties carried as little as possible to increase their mobility across ‘no man’s land’ and for more rapid movement when clearing the enemy trench. No webbing was worn, and men were not permitted to carry identification, maps, diaries, or to wear unit patches. Normal weapons plus steel helmets were worn; those without rifles carried ‘nut-crackers’ for hand-to-hand combat. Some specialist equipment was also employed: scouts, searchers, bombers, and signallers carried revolvers; and bayonet men, searchers, and bombers also carried electric torches.

The 39th Battalion history makes reference to raiders being given different uniforms (possibly uniforms without unit patches) for the raid. This was so that the Germans would ‘gain no accurate information if any were killed or taken prisoner.’[4] Finally, the raiding parties wore white arm bands (which were covered with sand bagging until ZERO Hour) in order to clearly distinguish them at night.

Figure 1: A simplified scheme of manoeuvre of the raids represented on the 1917 trench map but using contemporary military symbols.

Both raids were successful. The first raiding party from the 39th Battalion, led by Captain Norman Booth, were reported to have killed 30 Germans, with likely more killed by the opening artillery barrage.[5] This initial raiding party also captured two prisoners.[6] Sources suggest that the casualties during this raid range from three to five Australians killed in action, with a further 10 sustaining minor wounds, and one other with major wounds.

The 39th Battalion’s intelligence report the following day lists one soldier killed during the raid and another soldier and an officer dying of their wounds, while the battalion diary records that four soldiers and one officer were killed.[7] The 39th Battalion’s raid had such a great effect that a reinforcement garrison from the 12th Pioneer Battalion and the 103rd Regiment had to be brought up to support the German line.[8] They were attempting to repair the damaged wiring and dugouts from the 39th Battalion’s raid when the 40th Battalion’s raiding party struck them in complete disarray.

The raid of the 40th Battalion was described as the ‘most successful raid ever carried out by the battalion’[9] and the 40th Battalion history notes that ‘the whole plan was well thought out and carried out.’[10] The second raiding party was led by Lieutenant Henry Foster, consisted of three other officers and 73 other ranks, and killed 70 German soldiers with additional killed by mortar fire.[11]

A further three prisoners were captured, two of whom were wounded.[12] The right storming party, led by Lieutenant Ronald Swan, was met with no resistance and was faced with a ‘line full of bewildered Germans’ making their task relatively simple.[13] All parties were reported to have worked well, fiercely using bayonets, bombs, rifles, and revolvers resulting in a fearful enemy ‘scrambling’ out of the trenches and trying to escape by ‘running back overland.’[14]

Conclusion

This paper has reconstructed a little-known but very successful action of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) in Belgium in late 1917 – the Warneton Double Raid. The reconstruction has demonstrated the success possible following detailed preparation and planning and its violent execution by well-trained and well-practiced raiding parties.

The concentration of overwhelming force on a relatively limited objective and the innovation of near-identical attacks on the same stretch of trench several hours apart demonstrates innovation within the AIF. Despite the raids being highly efficient and successful, strangely they receive very limited attention in the Australian Official History. It is hoped that this paper addresses this omission and highlights the skill-of-arms that the raids represent in Australia’s WWI history.