Introduction

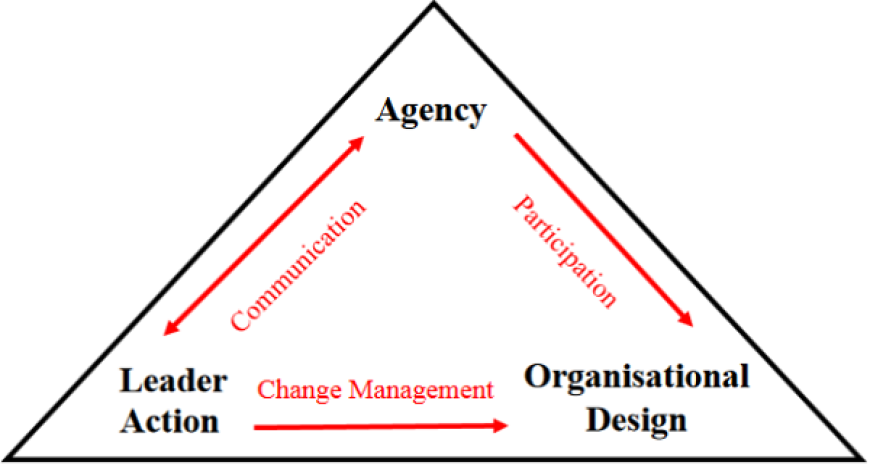

The proposed Engagement Triad Model (Figure 1) shows the interaction between the workforce, leaders and organisational design. Encouraging open and integrated relationships at work stimulates opportunities resulting in job satisfaction and positive workplace engagement. Gallup (2021) defines engaged employees as those ‘who are involved in, enthusiastic about and committed to their work and workplace.’ Having a positive, fulfilling work-related mindset allows people to feel they can deal with the demands of their jobs (Schaufeli, Bakker and Salanova, 2006) in an intentional, absorbing and energetic way (Joo and Lee, 2017). The opposite of this is low engagement where people are not able to apply their ‘preferred self’ to create connections to work and others while fulfilling their role and tasks in a meaningful way (Kahn, 1990). Using this narrative of workplace engagement, the Engagement Triad – Agency, Leader Action and Organisational Design – is a model that can connect people to an organisation’s purpose.

Figure 1: Engagement Triad – Elements Influencing Workplace Engagement

Fluctuation of engagement levels

High levels of engagement require people feeling they can communicate their needs and for organisations to be responsive to employee requirements. However, the foundation of military service is hierarchical and commonly viewed as transactional and mission-focused, which can undermine a people-focused culture. On the contrary, contemporary global leadership practices promote a transformational approach that encourages:

- responsiveness to people’s needs and desires

- an organisational design that is integrated and adaptive, and

- individuals being empowered, innovative and communicating widely.

It is the conflict between transactional and transformational approaches, obscured by underdeveloped or unresponsive leadership, that opposes high levels of engagement at work. Adding to this organisational dilemma, individuals have subjective views of satisfaction, success and well-being that also influence levels of engagement at work (Joo and Lee, 2017). This melting pot of behaviour informs and psychologically challenges a person’s commitment (Murch, 2021; Rousseau, 1989), causing employees to reconsider their organisation, job or role (Weiss, 1982). Consequently, workplace engagement can fluctuate depending on the:

- leadership climate

- emphasis on people-focused outcomes

- understanding and acceptance of the organisation’s purpose

- expectations of individuals

- implications of performance and achievements, and

- perceived and actual pressure at work.

These elements vary amongst servicemen and women and are difficult to measure, especially when change pressures are compounded by Army’s regular posting cycle.

So, what does disengagement at work look like? Whether a person is continuously disengaged or life circumstances cause temporary disengagement, individuals may not recognise the symptoms or may attribute them to factors outside of their control and therefore assign blame elsewhere.

Hudson (2010) describes an aspect of Attachment Theory (how attached/committed a person is to an organisation) that categorises negative, cynical, dissatisfied, ambivalent, preoccupied or dismissive people as disengaged employees with negative mental models of the organisation. Broadly, these insecure-attachment tendencies are emotional responses and biases that restrict clarity – leaving individuals either not motivated to work at the organisation’s standard or moved to actively undermine the organisation’s purpose.

Engagement Tcoriad

The Engagement Triad is a model that proposes Agency, Leader Action, and Organisational Design as being essential to encourage positive workplace engagement. The following section describes the Triad.

Agency. Phenomenal Will (Libet, 1999) or Self-agency (Wegner, 2002), herein referred to as agency, acknowledges that a person’s will to act is central to human psychology and is a preoccupation. Preston and Wegner (2005) capture the notion of innate human engagement using the activities of sensing, processing and acting to describe the engagement process. Limiting or controlling this intuitive process undermines the human desire for autonomous work. Autonomy is widely known as a condition that contributes to improved performance (Linley, Nielsen, Gillett and Biswas-Diener, 2010). Often falling short of perfect agency (Preston and Wegner, 2005) and succumbing to frequent errors due to biases (Kahneman, 2011), inadequate sensing, processing or acting – and can further deteriorate if not enhanced with education, practice or development. Agency requires competence and a safe environment to learn from mistakes (Murch, 2020) as an essential step in building trust and a climate of autonomy.

Risking a description of agency as an out-of-reach aspiration, soldiers must recognise the conscious effort required to connect with and be active within their organisation’s purpose. Wegner (2003) emphasises agency requires that a person’s thought and action must give priority, consistency and exclusivity to an event. When combined, these criteria ensure self-motivated contributions. Likewise, agency is not an ad-hoc occurrence or an event of coincidence; rather, each criterion is required for agency to exist:

- Priority – Action is planned and decisions are based on suitable information. Alternatives, consequences, and constraints are considered when planning.

- Consistency – Action must match what is intended. Deviation from the expected plan (unless planned) lowers satisfaction and undermines self-efficacy. Disconnection from the solution or purpose may occur when intended outcomes or achievements are not evident.

- Exclusivity – It is the person’s effort/contribution/performance/achievement that delivers the outcome/output/result.

Within a military context, the Australian Defence Force operates within an environment of mission command. This leadership philosophy works best when individuals exercise – and organisations expect – agency. However, indiscriminate agency or independent free-will that does not support an established mission, purpose, or goal undermines unified action. Like mission command, disciplined initiative (or disciplined agency) allows people to work within organisational intent and guidance.

Leader Action. Leader Action drives organisational design and connects, inspires and motivates people to believe in and contribute to the organisation’s purpose. Howell (2017) is adamant that engagement starts and ends with leadership. Further, according to Lewin (1946) simply collecting information without taking action or admiring a problem is inadequate. Encouraging positive agency reinforces the need for action and creates change momentum. However, without Leader Action mapping the way, the following implications exist:

- vision and goals will not be established

- people will not be suitably employed and developed

- resources will not be apportioned well

- integration of training will lack coherence, and

- engagement will fluctuate.

Leaders are expected to make decisions and act in ways that support individuals, teams and the organisation – each hierarchical level has responsibilities but requires a ‘people first’ outlook to ensure a leader’s mindset understands the impact on people. Decisions made and actions taken have a direct effect on the workforce and how engaged individuals feel. As an example, during 2021, the Australian Army conducted the Warrant Officer Support Pilot incorporating the Gallup Q12 Engagement Survey. The survey highlighted three essential areas that impact on the engagement levels of Army’s Warrant Officers Class One; namely, opportunities to learn and grow, encouragement to develop, and receiving feedback and recognition. Whether measuring senior soldiers or a global benchmark, Gallup identifies disengagement at work as an issue for all leaders, employees and organisations. The following lists offer reflection points or observations about a leader’s impact in the workplace:

- A leader’s effect on individuals to improve engagement:

- Provide frequent feedback on progress and achievements – this should be weekly and does not need to be formal. In trusted relationships feedback can be conversational and anecdotal.

- Communicate frequently – this provides role clarity.

- Encourage people to learn and grow and provide them time to develop – this can be professional mastery development or opportunities to immerse in other interests.

- Care for people by being involved in their development – a mentoring and coaching approach allows leaders and followers to learn together.

- The leader must be an example of self-development.

- Design learning and training that nests with team development and established goals and is aligned with the organisation’s purpose.

- Listen to background conversations (Ford, Ford and McNamara, 2002) to identify and understand individuals’ observations, experiences and issues that may oppose recent decisions.

- Observe for disengagement tendencies.

- A leader’s effect on teams to improve engagement:

- Participate in team and group activities – this builds inclusivity and trust.

- Communicate and follow up quickly to solve ambiguity.

- Seek input from the team to support training design and to improve future activities.

- Set challenging goals that stretch individuals, align to purpose and improve group cohesion.

- Empower emergent leaders to exercise leadership skills.

- Publicly recognise and reward the desired performance and standards that contribute to high performance.

- A leader’s effect on the organisation to improve engagement:

- Encourage consultation and collaboration across the organisation. Knowledge transfer is essential – a learning organisation does not restrict itself to silos of excellence.

- Frequently circulate amongst units, teams and individuals to identify and understand problems.

- Implement and support a reward and recognition system that reinforces the behaviours and values of the organisation.

- Encourage mission command (and agency) and accept mistakes as learning opportunities.

- Review organisational design ensuring the workforce functions effectively at work and grievances are listened to.

The meaningful efforts of leaders across organisational levels directly contribute to how people feel and perform at work. Leaders that accept this and communicate openly with their people provide the best opportunity to create change and improve organisational design.

Organisational Design. The third element of the Engagement Triad is Organisational Design. Design describes an organisation’s form, function, and required performance to conduct short and long-term activities while having capacity to respond to planned and unplanned change (Alter, 2010). Central to successful design is the need to integrate people with work processes and systems enabled by technology. A military achieves this when alignment with purpose and mission is clear and soldiers and teams are suitably resourced – enabling their efforts as contributions to collective outcomes. Design incorporates the general, characteristic and goal-oriented structures, processes, and policies that describe what an organisation provides and how work is done (Alter, 2010). This is determined with top-down direction using Leader Action, informed by workforce communication, to provide relevance and practicality. Importantly, frontline and mid-level leaders should have confidence and agency to apply design factors and inform decisions that support the nuanced needs of their people.

For many, the subject of Organisational Design would probably not grab their initial interest, but when contextualised as the doctrine of an organisation’s work systems- realisation of its importance escalates. Design is created by people for people; made difficult when not every person has the same needs. Nel and Little (2015) highlight the interplay of cause and effect when implementing design detail, so attention to human behaviour, social sciences, and positive psychology is warranted. Organisation and enterprise-level leaders must:

- understand the organisation’s strategy

- anticipate how planned interventions should work

- identify patterns that arise from human interaction with design elements

- establish communication channels to hear from the workforce, and

- implement a framework to review and amend ineffective design elements.

Conclusion

The Engagement Triad aims to connect people as informed and motivated actors with Organisational Design. Within a military environment, design is made up of prescribed policies, rules and regulations that are equally applicable to leaders and followers. Consequently, these imposed requirements, enforced by chains of command, create a transactional mindset that detracts from the notion of agency. Nevertheless, a person can proactively navigate Organisational Design and achieve successful outcomes when they are knowledgeable, understand work systems, are equipped for workflow processes, and trust their leaders. Interaction occurs on two levels; firstly through communication between leaders and soldiers taking the form of feedback, complaints, and compliments, and secondly, as participants in work requirements. Meeting Preston and Wegner’s (2005) ideals of human engagement, sensing, processing and acting is improved when people are connected, engaged, and believing in the organisation’s purpose.