We are approaching the end of our second decade in the 21st century and the scale of this century's technological advancements are just now beginning to dawn on the Australian Defence Force (ADF) as an organisation. The last 18 years have seen some extraordinary changes in information, communications & technology (ICT), national security interests and warfare. In September 2001, arguably the catalyst for our operational focus and tempo over the last 17 years, roughly 8.6% of the world’s population had access to the Internet. By December 2017, that number had exploded and 54.4% of the world’s population were connected to the internet, with approx 2.32 billion people using smart phones. Statistically monitored growth indicates that in the next five years the number of smart devices being used will increase to 6 billion. In addition to interconnectivity, individual aptitude for using technology is advancing at the same rate.

Up until the Defence White Paper of 2009, conflict in the cyber space was something that was discussed but wasn't a commitment[1]. That has changed. Tech advancements in the next decade are expected to continue apace, which, when you consider some of the target techs like artificial intelligence, augmented reality and facial recognition, it’s easy to believe. The problem is, the ADF’s Chief Information Officer Group (CIOG) may not be able to implement new tech as fast as it is evolving, a risk they have already identified in their Defence ICT Strategy 2016-2020[2]. This problem is already a reality in 2018 and it hamstrings administration. We also exacerbate the problem through implementation of bureaucracy, both at an organisational and unit level. This bureaucracy has been examined before at a Departmental level (for example the Dr. Allen Red Tape review in 2015), however at brigade and unit level we still suffer from self-imposed administrative procedures that have no basis in legislative obligations. Regardless, as the ADF’s primary asset is its people[3], and people require administering, this is a challenge that our organisation must address.

This article will examine the synchronisation shortfalls between administrative processes at unit level and the strategic implementation of ICT systems. In particular, it will explore how these two key factors combined have the capacity to achieve an immensely debilitating effect on capability.

To achieve this, the article will discuss the ADF’s strategic objectives as they relate to ICT and administration, our existing capabilities, and how they are employed. It will also scrutinise our bureaucratic procedures, particularly at formation level and below, as well as identifying where opportunities to streamline have been overlooked. Finally, the article will outline the collective impact these shortfalls have on the infantry battalion. By way of a disclaimer, it’s important to note that many of the above points have already been raised and relate to ADF wide policy, capabilities and processes. The reason for this blurring of lines and rough amalgamation is due to the overarching whole of department approach by CIOG and the experiences of the author.

Our heart is in the right place...

This argument is made tentatively. It feels as if the ADF has a collective interest in advancing its organic ICT capabilities. As mentioned above, the 2009 White Paper discussed the importance of building a capability in Cyberspace[4]. However in 2009, most members of the ADF probably weren’t able to log on and read the White Paper over the Defence Protected Network (DPN), which at the time was crusading along with Windows NT. Interestingly, the 2009 White Paper also spoke at length over several paragraphs about making Defence more efficient, reforming corporate functions (including ICT) and improving business[5]. However there was very limited discussion around how ICT would influence these changes.

The 2013 White Paper elaborates on the success of the strategic goals listed in 2009, citing that out of the reforms, Defence reduced operating costs by $3.3 Billion[6]. In 2013, Defence went further to outline it’s plans to advance our archaic network stating:

Most advanced capabilities have a critical dependency on information, in areas such as electromagnetic spectrum, communications, data networking and precision navigation. Defence will continue to upgrade its information systems to provide a 21st Century information and communications technology backbone that can support increasing requirements for mobility, high information volumes and processing, information sharing and protection against cyber attack. An important milestone was reached in April 2013 with Defence signing a $1.1 billion contract with Telstra which will enable Defence to transform its telecommunications technology in coming years. The project will significantly improve network performance and better integrate fixed telecommunications with satellite and tactical networks. (Defence White Paper 2013, p. 81)

The first two lines of this quote provide a broad intent for Defence to seek such upgrading and alludes to an aspiration that, in the future, Defence will be completely interconnected with a high speed, high functioning ICT capability. It almost seemed we were on track with CIOG conducting thorough analysis and delivering the Defence ICT Strategy 2016-2020, which this article will examine further below. However, what is concerning was how little attention was paid to ICT and administrative reform in the 2016 White Paper. Defence Reform was discussed, in line with the strategic directions listed in the preceding documents, however its focus on corporate enablers was largely limited to estate management. Eventually, the 2016 paper did manage a few paragraphs that described the Chief Information Officer as the ultimate authority on networks and which stressed the importance for interconnectivity when operating in the joint space. Yet the future of corporate governance and ICT simply got the one paragraph:

Defence will further consolidate its other enabling corporate services such as finance, human resource management and administration to minimise duplication and strengthen service delivery. (Defence White Paper 2016, p. 173)

To be fair, The Defence ICT Strategy 2016-2020 issued by CIOG does have a strong and reassuring idea of where ICT should be in the future and how it should be used for governance[7]. This document clearly demonstrates that CIOG have acknowledged the critiques raised by Defence staff regarding the ADF’s outdated processes and systems.

You may be beginning to question why this article has constantly been referring to the White Paper publications. In early September 2018, the new Chief of Army, Lieutenant General Rick Burr, made comment about the fact that the “rate of change is accelerating” and indicated a collective intent within Army to maintain pace. The broad outline of the stratagem that Army intended to use to maintain pace with change was through the Defence White Paper process. Therefore, if this is to be our primary means of adapting at an organisational level, its relevance is entirely appropriate.

White Paper aside, the CA’s brief, together with Commander Forces Command, Major General Fergus (Gus) McLachlan's, impromptu address at the Gallipoli Barracks Officer’s Mess the day after, both made strong reference to technology’s strong influence in the modern Army[8]. This reinforces that Defence has a general intent to adapt to, and exploit, technology as best as possible.

… our capabilities are not!

So the organisation wants to maximise the effect received when we harness technology. Yet we don’t really feel as if we are. The current application list on the DPN is in excess of 70 applications available for general users. We have a myriad of systems that achieve different things. For example:

- Webforms is our primary means of processing applications and consist of a specially design .ifm (desktop form document) files and .pdf files.

- Sharepoint is a web base collaborative application used for content sharing and management.

- The soon to be obsolete Business Reporting Tool is used to search for and identify information registered against someone’s PMKeyS. PMKeyS Self Service is used to manage individual pers administration and by managers to process requests from subordinates. This application transitioned to Defence One in August 2017, although it’s still listed as PMKey’s Self Service on the DPN homepage. The only noticeable change for end-users is the word ‘leave’ being substituted with ‘absence’.

- Microsoft Outlook, our integral email capability, supported by Lync for instant messaging.

- Internet Explorer (IE) to access HTTP pages (intranet or internet) unless you need to view a video, in which case you need Google Chrome. However, if it’s a YouTube clip you need IE with special permissions.

- DREAMS for remote users and deployed personnel.

- Microsoft Office Suite, the heart and sole of administration and instruction, all installed on Windows 7… or maybe Windows 10.

Finally, two applications we will discuss in slightly more depth, TASMIS (training area safety management and information system) and the fabled Objective. Most of these applications overlap with each other in some fashion by virtue of the administrative processes we have created, however very few are actually linked to each other.

TASMIS, as an application, has turned into one of our greatest success stories in this field. It progressively flows a request through the various channels to seek approvals in accordance with policy. It contains all the information required to draft a request and even has a training version to practice the development of range traces. It is linked to Microsoft Outlook and will generate an email to notify you when action has occurred with your request. It can be modified, have documents attached, its customisable for bespoke requests and well templated for generic ones.

On the other hand, there is the infamous Objective Enterprise Content Management (ECM). Designed as an information management system which is secure and more effective than the old Microsoft Windows G drive, it simply couldn’t keep up with the amount of data Defence thrust onto it.

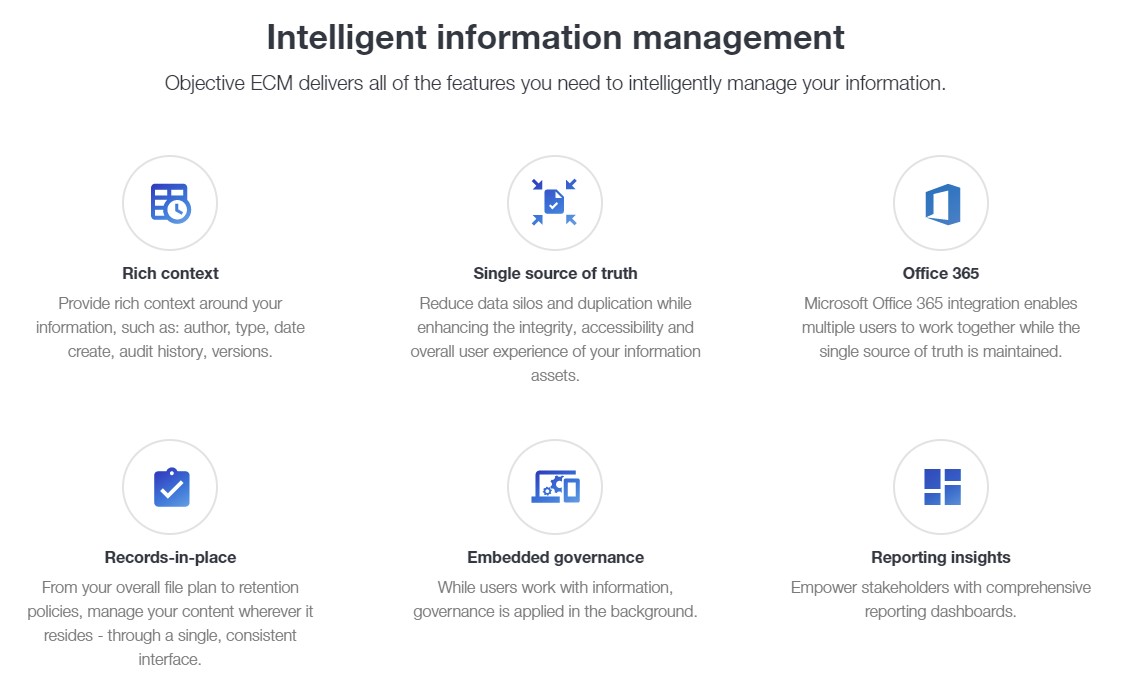

The official website for Objective boasts the following capabilities:

Objective is littered with log-in issues, storage capacity problems and, short of manually placing a link or email notification, is connected to absolutely 'zero' other systems. This last point is particularly important considering Objective’s main role is to store all of our important documentation and data for short and long-term periods. Some of these issues are entirely self-inflicted and will be discussed in depth below. However, it is simply one of the most significant inefficiencies within our ICT administrative processes, although it is not the only application that isn’t interconnected.

So why do we have these problems?

Arguably, there are three main theories behind why this is such an epidemic to our infrastructure in the ADF.

The first is that industry, in a capitalist society, thrives on competition. Successful companies need to maximise a customer’s need to procure multiple systems, thus making more money. That is achieved through having limited systems that aren’t completely compatible or connected. To solve a problem outright only creates a problem for the supplier. This isn’t necessarily uncommon or even illegal, unless it’s a case of planned obsolescence. The industry is capable of achieving this by exploiting the tender process.

The second reason is that we are transitioning too quickly; or technology and goals are evolving too quickly. As an organisation, we want to have a robust, secure system that can manage large amounts of data and achieve the things we want. But sometimes we don’t realise this until it has already progressed too far. CIOG have already identified the risk that they can’t keep pace - simply because an organisation as large as ours, with a secure nature, needs a precise and in-depth procurement process. Systems must be screened, tested, then implemented over a large network that too often is already out of date. Training must be delivered to all staff and support for new systems put in place during the transition from legacy systems[09]. Perhaps we just started too late or, more likely, we assessed the pace of change a decade and a half ago and strategically planned accordingly, falling behind as change sped up. This included planning for employment of personnel, distribution of funds and allocation of resources, all the while remaining accountable to Parliament. A slow process.

The third reason is that we simply haven’t completely evolved our traditional military administrative processes. We still have a Defence Writing Manual. It describes how we construct a Minute, a dot-point brief and other pre-electronic mail methods of conveying messages within an organisation. Some of these documents inform decisions and some are very appropriate for formal correspondence. However, general use of these documents to cover administrative process that the rest of the modern world do with Microsoft Outlook, makes this method of thinking more akin to flat-earth theory. In summary, the third reason is that we may just be stubbornly imprudent.

It’s hard to determine which of these are correct. Most likely, it’s a complex combination of all three. As an organisation accountable to the Australian Government and people, it’s very difficult to combat the first reason. The second is already being addressed by CIOG and the outlook is looking extremely promising. So that leaves us with our own self-debilitating bureaucracy.

Victims of our own bureaucracy

Without administrative processes, there is no doubt that any organisation would struggle to manage their personnel and resources. This article has already established how interrelated these processes are with technological infrastructure. A strong ICT capability can enable a streamlined and networked information flow, providing individuals and organisation the ability to maximise efficiency. However, this is something that cannot be achieved without careful design and planning, which is difficult without causing frictions and even more difficult to keep current.

The ADF has made a strong attempt to develop a fairly robust ICT infrastructure. However, as stated above, it has desperately attempted to hold onto legacy systems that are archaic in nature. This could be for a multitude of reasons, such as tradition, decision accountability, ignorance, or a slow adaption cycle (specifically for individuals and small teams close to the end user). These reasons are largely just a broad assessment but they are informed by flaws in the existing systems. Some of these problems may seem insignificant to the larger departments but the impact on small teams within the infantry battalions, our specific focus, is significant.

How this effects the end user

To build on this focus, a platoon headquarters (PHQ) in an infantry battalion will be the example. In the design of training, the PHQ is required to develop a program that specifies the intent and conduct. To put the plan into action, the PHQ needs to use TASMIS to make the range and training area bookings. Within the TASMIS booking, the PHQ can specify what the activity is, how many people will be participating and what equipment is required. The TASMIS booking then gets sent off through the various approval channels. The PHQ can use the application to search for Range Standing Orders, can upload a Range Instruction onto the program for all parties to see, including the Unit Operations Cell, Range Control, and any other key stakeholders. TASMIS will update all relevant stakeholders via email. PHQ need to issue orders, ensure enablers are organised and any revision is provided or lessons delivered. Templated instructions, orders, risk assessments, training programs and lessons can be amended to produce a suitable product. A good example of how an application, well networked and specifically tailored can make processing efficient.

However, for many other processes that the PHQ must undertake, the applications fail to provide the most efficient and seamless support. Objective’s filing system imposed by CIOG is somewhat irrelevant and alien to end users, adding significant friction to filing and making finding information difficult. Information is often isolated from unit to unit, minimising the ability to network effectively between organisations - particularly difficult for a PHQ planning an activity that was run by a different unit the previous year. This problem is then further compounded by the posting cycle, moving key personnel on from positions, leaving only post-activity reviews and other critical documentation filed in the ADF’s data management system. This fundamentally denies the infantry battalions the ability to maintain an all-informed net, turning Objective into a computer equivalent of Narnia.

Arguably, Sharepoint is supposed to fill the gap for collaboration of information. However, it requires a HTTP browser to function and it lacks the security settings and data storage capability to fully provide this capability. Should PHQ’s start uploading every training program, administration instruction, performance appraisal report (PAR) and risk assessment onto Sharepoint, the system will grind to a halt faster than the G Drives.

Regardless, many infantry battalions still attempt to conduct administration in a hybrid soft/hard copy environment. Knowing that the documents will eventually need to be stored on Objective, simply because of the size of them, most documents must be created (in accordance with the Defence Writing Manual) printed, signed, and a coversheet attached before being scanned back into Objective. Noting that scanners are not openly available to each PHQ, the company clerk provides that support. These documents are then held in a folder in Objective, the coversheet emailed through to the decision maker, who in many cases must print, sign and re-scan. For significant decisions, this is understandable. For routine administration that has existing applications in place, this is arguably extreme. Alternatively, emails (including templated ones) can be electronically stored with the entire email chain intact, time stamped, information contained within, and significantly simpler to process.

Considering most units will have their own administrative process that are designed by staff officers with the support of the clerks, in accordance with policy, and all catering to their superior's preference, it’s difficult to provide more solutions. Each unit would need to re-asses their own processes, with hierarchy examining the benefits of defence writing and the time and resources it consumes for little benefit. Obviously our technology has a long way to come, with Web Forms still giving error messages in French in 2018, the same year Google has released a set of headphones that can actively translate in real time. After reviewing the strategic ICT objectives outlined by CIOG, the future looks promising. We just need to get there.