In the early 2000’s, organisations like NITEworks in the UK and ODIS (formerly RPDE) in Australia explored how new technology could change warfighting. One insight from that time concerned senior Defence leaders, their 25 years of service taught them ‘the pace of tech change’ and led to an inability to accurately judge the future pace of change of non-military technology i.e. they thought commercial technology would evolve at a similar (slow) pace to the military.

It’s been 20 years since those think tanks first stood up. Has the military mind changed? Whilst we typically talk Army on The Cove, I’d like to use the Future Submarine Program as our technology case study – perhaps it will allow we who wear green to interact less emotionally with the question – is Army best placed to judge the future of Army technology?

The Technology Experience Paradox

In the Future Submarine Program debate we hear variously that the speed of autonomous systems advances is not fast enough to remove the need for people in Australia’s fleet of Attack Class submarines, currently in design. Yes, eventually intelligent autonomous technology will catch up and Defence will have a reliable unmanned option to consider, but right now it’s just not viable.

But as we talk down the viability of autonomous options in submarines, we talk up the viability of new advanced batteries, revolutionary diesel pump-jets, underwater stealth and sensor systems – many of which have technology readiness challenges comparable to sub-surface long-range autonomy.

Batteries, diesel engines, these are all of course extensions to existing technologies, they make sense to a risk management mindset – we are iterating existing technology. But the submarine stealth industry doesn’t have a civil and commercial sector investing multi-billions in it – therefore can we say all these submarine technologies are advancing at a similar rate to autonomy?

It’s true that the US, British and French will co-invest and, to an extent share submarines advanced thinking on the more cutting edge elements of Australia’s submarines program – it’s a close community with shared strategic interests. But why does Defence think these more traditional submarine technology challenges can be overcome in the short term where intelligent autonomy cannot?

This isn’t to say the challenges around autonomous long-range long-endurance underwater systems is easy. It certainly is not. But you know what it is – it’s similar. It’s similar to the sorts of challenges we are seeing civil scientists currently deal with in robotic exploration of deep space. It’s similar to the autonomous vehicles we are currently seeing on our roads and in our skies.

For military tech with civil applications we should expect ‘related investment benefits’. Do we bet on a technology that has read-across from vast commercial research investments, or do we bet on highly secretive, closely held, limited use technologies that enable us to keep a human crew hidden underwater for months in one of 12 expensive to build and very expensive to lose conventional submarines?

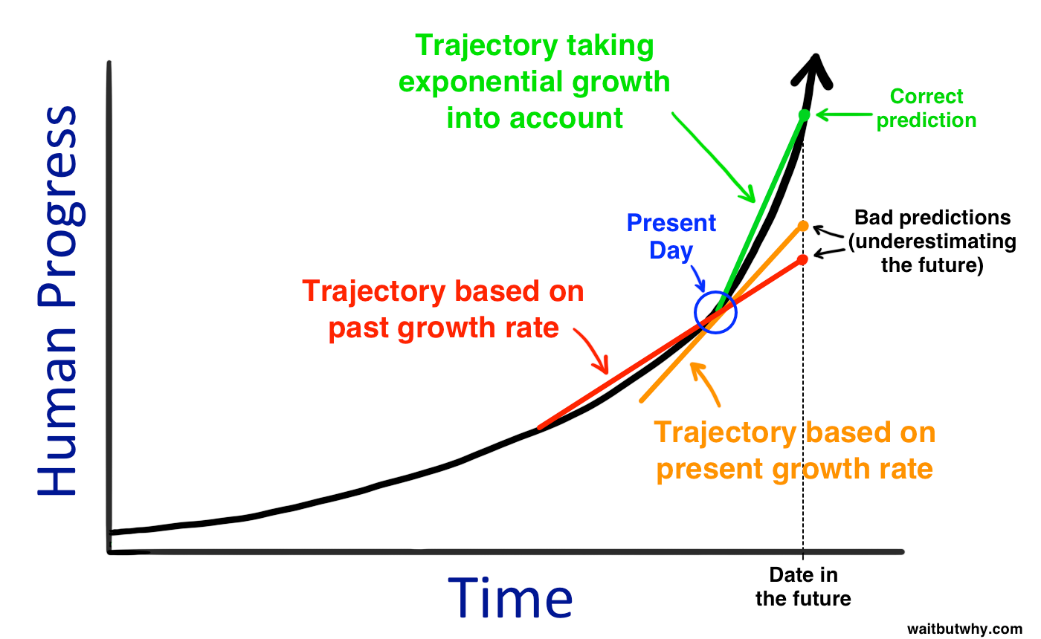

The reality is that the commercial technology cycle times for autonomous systems is likely racing faster than defence decision makers perceive. This might be expressed as a senior leader today saying '…In 20 years’ time I look forward to seeing a mature unmanned submarine/tank/aircraft…' And in a funny way they’re right. Left to itself, Defence Industry will match the expectations of its Defence customer. This is an extension of the 'Conspiracy of Optimism' argument. Not only does the defence sector buyer and the seller conspire to be comfortable with (retrospectively) difficult scope, tight schedules and too small budgets – they also contrive to form the same view on future technology options.

This of course makes sense to the involved parties. Does a Defence Prime want their sector disrupted by a Silicon Valley entrepreneur? No. In some capability development organisations this issue around autonomous assets gets grouped into the ‘expendable or defendable’ argument.

Expendable or Defendable

In a nutshell, defence platforms are either expensive, highly capable, few, piloted by humans and therefore necessarily ‘defendable’. Or you choose to acquire assets that are cheap, less capable, multitudinous, unmanned and correspondingly ‘expendable’.

It’s a spectrum of course – one could target the mid-point of the spectrum, and select 40 quite capable, less expensive, largely autonomous submarines. Frankly, why wouldn’t a nation do that if it were on the table? Submariners are hard to find, a 40 submarine fleet threat is better than 12 in a strategic planning sense – what’s the down-side?

Well, one issue might be cultural. It’s hard to grow your next Service Chief when – for the last 200 years – you’ve predominantly selected your best fighter pilot, ship/submarine captain or armoured vehicle operator as your most senior leader. But really, I sense this isn’t as powerful a blockage to more radical autonomous change as many would like to believe. Our modern defence leaders understand that a de-peopled battlespace is inevitable and good.

So, what is really blocking courageous choices around (specifically) advanced intelligent systems, or (generally) radical technology choice in Defence? To our thesis, I wonder whether it’s an inability to fully appreciate that tech cycle times have changed, have accelerated and are continuing to accelerate.

Know a potentially transformative technology by its piecemeal treatment

One could argue that our unwillingness to engage with areas like intelligence in autonomy is revealed by planning that deliberately limits capability choices to niche systems. Back to our submarine example. The thinking is that military advantage will come from a bespoke pump jet, or propeller, or tiles, or battery advances. But non-defence experience might say future advantage subsurface warfare will more likely come from the fast deployment of advanced software to an extant fleet, or from additive manufacturing that speeds up asset deployment or repair. Our experienced leaders think of capability in 30-year cycles whilst our commercial cousins describe a 30-week update as slow.

Australia is investing $50b+ in ‘expensive defendable technology’ just as the world makes less expensive, autonomous technology an option within grasp. This isn’t easy – but won’t young ADF members be more excited at the prospect of Australia crafting the first of the advanced autonomous submarines that dominate the oceans beyond 2100, than the last of the manned submarines that simply occupy them?

Apply this thinking to Land 400 Ph3, to the Soldier Combat Ensemble, to Self-Propelled Guns and Electronic Warfare – are we judging the speed of technological change correctly? Are we in uniform even best placed to make such judgements?

Empowering Radical Thinking

At a September 2020 gathering of the War College’s Perry Group, science fiction narrative was used to explore what the future might look like for the ADF. One team fantasised a future ADF of only 1,000 human members, leading an Artificial Intelligence (AI) enabled force. Perhaps most fascinating was the geo-politics that supported this force design outcome – that Australia’s allies ‘carried us’ whilst we deliberately took a backward step to create this 6th generation force. Such global collaboration seems a crucial part of any nation’s decisions to radically reform.

Of course, the aim of such sessions is to cause listeners to ask – why not?

Well there are lots of reasons why this may not be an accessible future for us today. But it’s not because of technology. The principle barrier to Defence adopting more radical force structures is not government, budgets, tech or the law – it’s us. The people that make up Defence and our institution’s culture. We (or perhaps more correctly our collective mindset) are the single biggest barrier to change.

Now there are lots of reasons why barriers to radical change are a good thing in a Defence Department. Change is risky. Our Australian communities and allies generally don’t want to risk systemic failure in the pursuit of an unproven capability edge (at least, not outside of existential threat scenarios). Caution is good.

Re-setting our Risk Appetite

And so we end where we began, with world technology changing at a pace we in Army – by our very nature, in our DNA – are ill prepared to judge. We have institutional and cultural bias to caution and conservatism, left to ourselves we will iterate known technology even in the face of fierce evidence that alternatives are attracting orders of magnitude more civil investment.

The reader might be thinking now – so what? Who has a problem with a Defence Force, or an Army that is conservative around technology choice? We’ve seen how leading-edge choices lead to delay and inefficient funding outcomes. Agreed. Maybe this doesn’t matter. And maybe the alternative is worse – maybe having non-Army technologists involved in our decisions will just lead to even greater friction, confusion, tension and delay.

But these aren’t ‘either-or’ decisions, the better question is where on the spectrum does Army want to be, and where are we now? And do we have enough ‘challenging’ technology projects in the program in 2020-30 to ensure we don’t (in the eyes of adversaries) find ourselves too conservative – too predictable.

Note: Chart from https://boingboing.net/2015/01/23/the-road-to-superintelligen.html

The author worked at both NITEworks and RPDE