This is a two part series and is a collection of my personal experience on terrain analysis and LWD 5-1-4 The Military Appreciation Process (MAP). This article seeks to incorporate elements of enemy analysis into terrain analysis and discuss terrain relative to the enemy and friendly action/reaction cycle. Although founded in doctrine, it is important to note this article does deviate slightly from it.

This article is targeted at the Corporal, Lieutenant and junior Captain ranks.

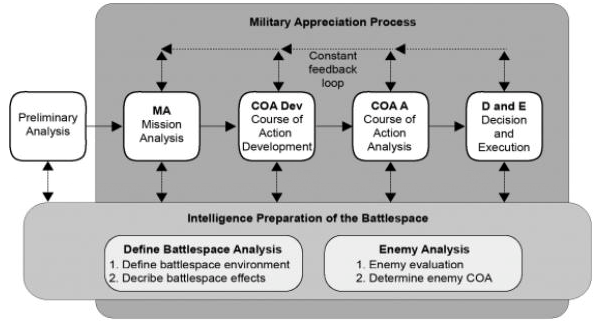

The MAP is a five-step process supported by the continuous assessment and analysis of the battle space, conducted through the Intelligence Preparation of the Battlespace (IPB) and terrain analysis as seen in the image to the left.

Presently, terrain analysis risks becoming characterised as an exercise in ‘procedural colouring-in’, which dilutes its true value. This article seeks to illustrate the utility of terrain analysis by providing examples of usable deductions for the practitioner whilst also demonstrating the utility of incorporating enemy analysis into your terrain analysis. Part one covers defining the battlespace environment and describe battlespace effects (up to and including obstacles as a part of OCOKA). Part Two will cover Key and Decisive Terrain and Avenues of Approach in a detailed manner.

IPB – Define the battle space environment

Identify the planning time. Identifying the planning time available to plan the mission is crucial and allows a planner to make some immediate decisions. If planning time is short, either intuitive or deliberate planning can occur. For now, we will focus on deliberate planning.

Identify environmental characteristics. Geography, terrain and weather need to be considered relative to the Area of Operation (AO), your mission, and your anticipated enemy mission. It is often best to collect this information early to inform considerations in IPB Step 2 – Describe Battlespace Effects. The AO is usually given to section, platoon or company commanders. The critical purpose of an AO is the delegation of manoeuvre effects based on the ratio of space available. Coordination of direct and indirect fires is a by-product of this delegation.

The AO, and more importantly boundaries, are not just lines on a map. To simplify it, boundaries are similar to a trace you draw for a range practice; you cannot shoot over it, you cannot walk outside of it, and there are specific tasks you need to achieve within it. It has been given to you for a reason, and when considering your AO you should ask yourself some key questions relative to your mission:

- What is my mission?

- Is the size of the AO realistic for my task?

- What areas are most relevant to achieving my mission?

- What areas are most relevant to the enemy achieving their mission?

I appreciate these questions may jump ahead in terms of the MAP. However, they present 5 minutes of critical thought worthy of your time. The reason will become apparent later.

Determining IRs and making assumptions. The final components of defining the battlespace environment is ‘determining IRs and making assumptions’. This is difficult to do early on in the planning phase and doesn’t really come into play until the next step.

IPB – Describe battlespace effects

Describing Battlespace Effects is comprised of four components namely: terrain analysis, weather analysis, analysis of other battlespace characteristics and the analysis of the combined battlespace effects. It is here where our focus will shift to.

The figures below derived from LWD 5-1-4, provide examples of combined battlespace effects of observation, fields of fire, cover and concealment and restricted movement. The issue from a practitioner’s perspective is that these figures omit critical elements such as terrain analysis, as there is only so much information that can depicted in a small drawing. These omitted critical elements will now be discussed.

Terrain analysis

The Modified Combined Obstacle Overlay (MCOO) is not a waste of effort if conducted correctly. The most important part of any terrain analysis is the deductions drawn from this analysis; without these deductions, a practitioner has achieved nothing other than colouring-in for 45min. Here are some tips on how to draw out these deductions.

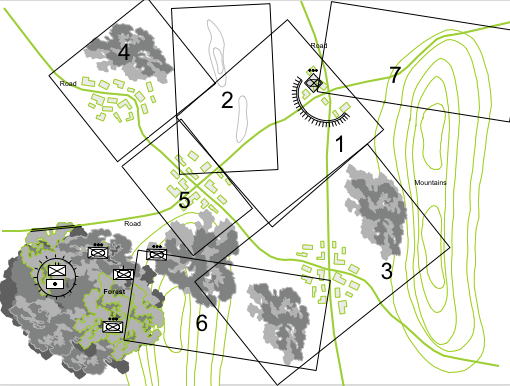

Define the area/s that you are going to analyse and prioritise accordingly. Your AO is generally going to be a diverse area covering at least a few square kilometres; therefore, you should seek to break your AO into key areas and prioritise these so that you work on, and gain deductions from, the most important areas first. Prioritising these areas is also good if you are running out of time for terrain analysis IAW your planning timeline, as you can concentrate effort on these areas. In order to prioritise these areas, you must first know your mission and your enemy’s likely mission. This will allow you to contextualise the terrain relative to your problem (this is the first deviation from doctrine). For example, imagine you are the OC of a mechanised infantry company tasked with clearing a known enemy mechanised platoon size element (see image below).

To prioritise the terrain, a practitioner would be looking for:

- the objective

- avenues to the objective

- possible fire support locations

- possible reinforcing / withdrawal routes for the enemy (See image below).

The key take away here is to prioritise the terrain relative to the problem.

Area 1 – The objective

Area 2 – Possible Fire Support / Observation post (OP) locations

Area 3 – Southern Ave of Approach

Area 4 – Western Ave of Approach

Area 5 – Complex Terrain, possible OP locations / Ave of approach

Area 6 – Concealed Approaches

It is only when these terrain areas are prioritised that terrain analysis can be examined in accordance with OCOKA. We will focus on area 1 in the above example.

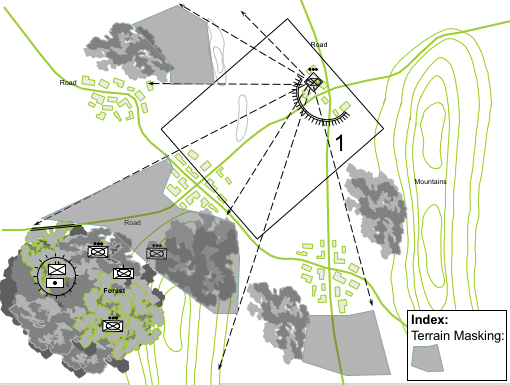

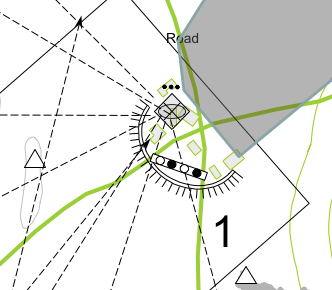

Observation fields of fire

In this example the observation fields of fire would be taken from an enemy and friendly perspective as this is the area where interaction between the two forces is most probable. Image left indicates the observation/fields of fire and cover and concealment from the enemy position and the key deduction would be as follows: (See Area 1 Deductions example). This process is then carried through for each position within Area 1 that is likely to have observation of, or from, the enemy position to inform planning. Once this is finalised for Area 1, you can transition to obstacles, key and decisive terrain and avenues of approach.

Obstacles

Natural obstacles need to be considered relevant to how this would increase friction on own force and enemy force movement. If a planner is considering options to ‘go around’ an obstacle, it is safe to assume that the enemy has also considered this option and could use this as an opportunity to further enhance the natural frictions this action would incur. You don’t necessarily need to consider means or options to pre-empt this action (it would take too long and probably bog down planning significantly) but it is important to make sure you have the means available to you as a planner and (commander) to defeat, or tolerate, any extra frictions at these locations. A reliance on reconnaissance gaining observation onto these locations could at least give you an indication of your enemy intent. Alternatively; minor terrain based PIR can be created, such as ‘what is the viability of the crossing point Vic NAI XX' which in layman’s terms means 'can I cross the river/stream/restricted terrain with the type of vehicle I am trying to use to get across it’ etc. It is important to consider enemy interference now, as opposed to COA Analysis or enemy analysis, as there is potentially a lot of wasted planning effort in the early stages for avenues of approach or routes around obstacles that you later find to be untenable. As such, the information in your warning order, released after Mission Analysis, becomes moot and confuses the situation for your subordinates. One could potentially view this as increasing the time a planner uses to develop and plan and, when attempting to adhere to the 1/3, 2/3 rule become a waste of time. That is not true. In your planning timeline you are taking time from these steps and putting it to better use in terrain analysis.

In terms of man-made obstacles encountered in planning, it is important to ask yourself the following questions:

- Why would the enemy put the obstacle in that location?

- How would placing an obstacle in that location assist with the enemy plan?

- What reaction or response is the enemy attempting to elicit from me by placing the obstacle there?

- If the enemy has placed an obstacle in that location, it is likely to be covered by fire and view, if so, where would that be from?

- If the enemy is eliciting a response that sees me not breach that obstacle, what sort of alternate effect are they trying to achieve?

These questions are, literally, enemy analysis and not terrain analysis. The purpose of asking these questions now, as opposed to in enemy analysis, is so that these questions allow the planner to answer more terrain pertinent questions such as, are there routes around the minefield? If so, do these lead to locations that are more likely to increase friction or expose a flank? There is an interplay between terrain and enemy analysis here and there is a risk of bogging down but it is very important to do so in this stage.

The enemy has placed a mixed mine field orientated to the south. It is likely the enemy has placed that obstacle in that location to defend against an approach along what has been assessed as the line of expectation, to use the counter to B.H. Liddell-Harts ‘line of least expectation’. The obstacle assists the enemy because it creates a protective effect close into the defensive position. The fact that the enemy has placed this obstacle in a relatively obvious position should raise an eyebrow if you are the planner. Therefore, what response is the enemy attempting to elicit from the planner?

- Perhaps, the obstacle is a dummy, designed purely to slow planning down and confuse the issue?

- Alternatively, perhaps it is an actual minefield protecting against the most likely avenue of approach; however, alternatively it could be placed in that location to deter an opposing force from approaching from that direction and choose the longer, but easier approach to the West of the Position?

There is no end to the types of questions that could be asked about that minefield, and no end to the derivations of same questions that could be asked about a MG nest, a wire obstacle, a vehicle pit, antenna farm, supply cache, a suspicious looking part of the road which may harbour an IED. The danger is a novice planner would become trapped in a literal minefield of rabbit holes thinking about these questions, and produce an absurd list of PIRs and SIRs for a company clearance task.

This is where the relative nature of the enemy’s mission and purpose combines with terrain analysis. This is a point where a planner could borrow time from enemy analysis and consider, briefly, what the enemy’s mission and purpose is.

- If it is an offensive enemy: obstacles and fighting positions likely light and temporary measure to facilitate short halt and/or to momentarily fix an opposing force for mobile envelopment by flanking units to continue advance momentum.

- If it is a delaying enemy: obstacles and fighting positions are likely hastily emplaced under-resourced and time restricted, and are of minimally sufficient quality to achieve the required time delay, with a bias for engaging at longest ranges possible prior to swift disengagement.

- If it is a defensive enemy: obstacles and fighting positions are likely well-resourced, deliberately placed, interwoven and designed to achieve fix for destruction fires or envelopment by a CATK force. Enemy will likely be well resourced, have sentries, reserves, direct and indirect fire plan, ability to surge ay multiple points, and will force attackers into costly close combat.

These questions and deductions are for enemy analysis not terrain analysis but they change the considerations for terrain due to the relative nature of the problem. There is fundamentally no point in assessing the lines of inter-visibility for an enemy unlikely to use these tactics. These are also just thoughts and only take the time necessary to think of these considerations and perhaps only gain a small insight into how your enemy might fight. In the end, the purpose of the MAP is to defeat your enemy, not the terrain. A minor example could be ‘if’ I seek to go around a particular obstacle it could be an option for the enemy to seek to frustrate this action; I therefore need to consider this when developing my COA and perhaps find another alternate route or at least protect myself against this, or even expect this action thus requiring me to add further time to my appreciation for how long this mission will take.'

This is the end of part one. It is hoped, if nothing else, the following is left to resonate with you:

- Analyse the terrain relative to you and your enemies mission

- Break down your AO in order of priority and focus for efforts in this manner

- Consider the ‘what if’s’ now, instead of later in COA Development and jot them down with a reminder to carry them forward into the next steps otherwise the MCOO would be a big waste of effort.

Part Two will focus on answering initial terrain information requirements, the relative nature of key and decisive terrain, and the importance of analysing your initial reflex reaction to the problem and determining how the enemy might conceptualise your design for battle.