From the Author: Parts of this Cove article are based on a forthcoming Australian Army Journal article by the same author, titled ‘A Central Pillar of the Army Profession: The Conceptual Evolution of the Australian Army’s and Australian Defence Force’s Operational and Tactical Planning Processes’. Readers seeking a more detailed comparative analysis of the new and old planning processes should consult this other article once it becomes available.

In November 2024, the Australian Defence Force (ADF) published a new planning doctrine, Australian Defence Force – Integration – 5—Decision-Making and Planning Processes. This publication superseded two previous planning doctrine publications: Australian Defence Doctrine Publication 5.0.1—Joint Military Appreciation Process, which was an ADF joint doctrine publication, and the Army’s Land Warfare Doctrine 5-1-4—Military Appreciation Process. This article provides a ‘soldier’s five’ that summarises the new doctrine and the key ways that it differs from the publications it replaced. It is assumed that readers will be familiar with the previous doctrine publications and the planning processes they contained.

I. Four processes to two: The big picture change

Decision-Making and Planning Processes contains two inter-related planning processes:

- Immediate Decision-Making Process (IDMP), which is designed to assist a commander to quickly appraise a situation, determine a response, and – depending on the context – either issue orders to subordinates or issue guidance to planning staff.

- Deliberate Military Appreciation Process (DMAP), which is designed to be undertaken by a planning staff in support of a commander and completed over a longer timeframe than IDMP.

These two new processes have replaced the four processes contained in the previous two doctrine publications. The processes they replaced are the Staff Military Appreciation Process (SMAP), designed for use by staff in land domain tactical headquarters; the Individual Military Appreciation Process (IMAP), designed for use by individual commanders prior to execution; the Combat Military Appreciation Process (CMAP), designed for rapid post-execution responses to changing situations; and the Joint Military Appreciation Process (JMAP), which was designed for use by staff in joint operational level headquarters. Because they have replaced a range of tactical and operational level planning processes, IDMP and DMAP are designed for use by commanders and planners at both levels.

II. Individual Decision-Making Process: Summary

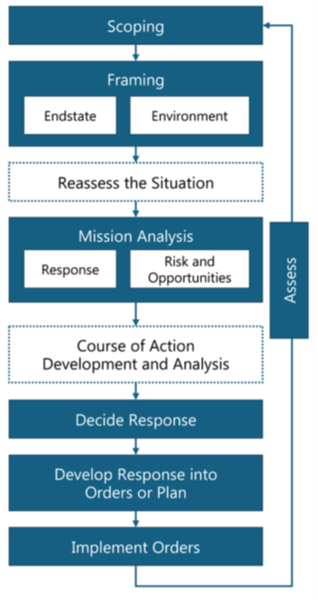

The IDMP is completed by a commander individually and has seven elements:

- Scoping – the commander checks their understanding of the situation.

- Framing – the commander pattern matches their experience to the current situation, determines a desired end state, and defines the environment and the problem.

- Mission analysis – the commander uses deductive reasoning to determine a range of satisfactory responses to the situation, environment, and problem – which will achieve the end state. These responses factor in consideration of risks and opportunities.

- Decide response – the commander decides which response they will implement.

- Develop response into orders or plan – the response to be implemented is developed into a set of executable orders, or into direction and guidance for planning staff (see the section below on links to DMAP).

- Implement orders – as the title implies.

- Assess – the commander must continually assess the situation and the effectiveness of their response during both preparation and execution. Assessment must take risks and opportunities into account. If the response is assessed at any point to be unsatisfactory, or the end state reached, then the commander starts the process again.

Two additional elements may also be added, depending on the context:

- Reassess the situation – this occurs between framing and mission analysis, if scoping and framing determines that the commander does not possess enough information. The commander may reduce the scope of the task, request additional resources, or change the nature of the task. Approval from a higher commander may be required. If there is a planning staff, the commander may issue them direction to conduct a detailed analysis of a particular area to resolve uncertainties.

- Course of action development and analysis – this occurs between mission analysis and decide response, if the commander cannot intuitively determine a suitable response. If working individually, the commander may develop a detailed course of action (COA) using analysis. If they have a planning staff, they may issue guidance for the staff to develop one or more COAs or, alternatively, use the staff to help test possible response options they have developed.

The IDMP steps and their sequence are shown in Figure 1 (source: Decision Making and Planning Processes, page 27).

Figure 1. Immediate Decision-Making Process

IDMP is intended to be rapid and intuitive, using pattern matching to enable commanders to determine suitable response options. This newly-introduced method requires training in pattern recognition, and a chapter is included in the Decision-Making and Planning Processes doctrine publication that discusses requirements for effectively training commanders and planning staff in this method (chapter 10). Accordingly, response options should be rapidly identified rather than resulting from detailed, protracted consideration.

III. Deliberate Military Appreciation Process: Summary

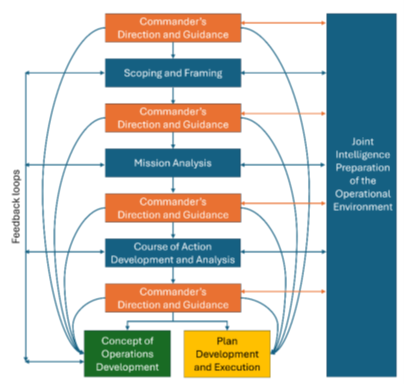

DMAP is undertaken by a planning staff, with ongoing guidance from the commander. It consists of three steps, each of which contains several activities. These are summarised below.

- Scoping and framing. This step confirms that the commander and planning team understand the nature of the problem to be solved. It establishes an operational risk management process based on identifying risks, likelihood and consequences, and mitigations. A newly-included method called a ‘staff estimate’, which contains a snapshot of key information and planning outcomes, is established in this step but requires staff to continually update and supplement it throughout the rest of the process. Amongst the many elements the staff estimate contains are the mission, situation, analysis of adversary courses of action, comparison of possible friendly courses of action, and key assumptions.

- Mission analysis. The most substantial step, this determines objectives (achieving all objectives enables the end state determined by the commander during their IDMP to be reached), decisive actions and tasks. Decisive actions are individual activities required to achieve objectives, and each decisive action may require completion of one or more tasks. Tasks should be as simple and straightforward as possible to complete. A mission statement is determined, limitations identified, and decisive actions are sequenced in space and time along lines of operation that each lead to an objective. A centre of gravity analysis is conducted early in this step. It identifies adversary vulnerabilities that can be targeted, own vulnerabilities that need to be protected, and defeat mechanisms that enable related tasks to be incorporated into the plan. Course of action sketches and statements are produced at the end of this step. These contain a broad schematic of how an operation may unfold.

- Course of action development and analysis. At least one, sometimes more, COA are developed in detail, enabling all tasks, decisive actions and objectives to be achieved. COA are then tested through the conduct of a wargame, enabling improvements to be identified and incorporated.

These three steps are supported by two complementary activities:

- Joint Intelligence Preparation of the Operational Environment. This independent activity occurs concurrently to the DMAP. It analyses the environment, adversary, and other major stakeholders, enabling possible adversary actions to be identified and countered.

- When the commander is satisfied that they now have enough information to make a decision and issue direction for actions to be taken, they may transition to either ‘concept of operations development’ or ‘plan development and execution’. This may occur at any time, regardless of the point in the DMAP that the staff have reached. This activity takes DMAP’s outcomes and finalises them for implementation. Depending on the operation, this may be as simple as writing and issuing orders, or it may involve development of several detailed supporting plans and assessment measures.

The DMAP steps, their sequence, and the two complementary activities are shown in Figure 2 (source: Decision Making and Planning Processes, page 10).

Figure 2. Deliberate Military Appreciation Process

IV. Relationship between the two new processes

Several aspects of IDMP and DMAP deliberately overlap, with the complementary relationship between the two processes being that the commander uses the IDMP to identify key inputs to, and requirements from, DMAP. They also use the information gaps and resulting questions identified during IDMP – and their assessment of available planning time – to consider which parts of DMAP need to be completed, and which can be abbreviated or omitted. This occurs because DMAP is comprehensive but very lengthy and completing all activities may not be possible in all circumstances. Indeed, the commander is encouraged to determine which DMAP components can be omitted, to make decisions as quickly as possible while still ensuring the course of action is satisfactory enough to meet situational needs.

V. Key changes from the previous processes

The content and focus of the new planning processes differs from those it replaced in the following key ways: (Note: this list summarises only the most significant changes from the previous planning processes. There are several changes, many of them relatively minor. Accordingly, this list should be considered as indicative, not exhaustive)

- DMAP is commander-centric rather than staff-centric. There is a greatly expanded role and scope for ‘commander’s guidance’ to be given between each step. How a commander develops and delivers this guidance is contained in a new chapter (chapter 4), which explains that the commander needs to understand the situation, visualise options, describe responses, then direct action. IDMP is the means by which the commander does this. Although CMAP and IMAP were designed for use by individual commanders, these processes were nowhere near as versatile as IDMP, which can be used to develop either orders to subordinates or guidance to planning staff.

- Greater emphasis has been placed on speed and intuition rather than analysis in decision-making. This is particularly the case in IDMP, which uses pattern matching as its key intuitive decision-making tool. Pattern matching is a process in which the current situation is assessed against several possible solutions that a commander was exposed to during training or in their prior experience. This is done rapidly and intuitively, with the commander seeking to recognise patterns then respond in a way that is satisfactory to meet the needs of the situation. Analysis is still an important part of planning, but speed and intuition are now acknowledged as playing an important role in effective decision-making.

- Some new areas of discussion have been included. Chapter 8 discusses how to effectively adapt a plan during implementation, elaborating methods that support this. Chapter 9 discusses aspects of a plan that could be included in annexes, branch plans, sequels, etc., such as sustainment and logistics. Some of the methods included in this chapter, such as event overlays, are derived from SMAP; however, much of its discussion is new. Inclusion of this new material will likely benefit specialist staff who are required to support the planning effort. Furthermore, this chapter captures lessons from ADF operations over the last few decades and includes discussion of planning considerations for force rotations, movement planning, and reception, staging, onward movement, and integration of personnel.

- Enhanced guidance for adaptation and deception planning. In addition to being feasible, acceptable, suitable, sustainable (and, where multiple COAs are developed, distinguishable), a plan must also consider adaptation and deception. Accordingly, the acronym for the COA test, which is now done by the commander as part of their IDMP, has changed from FASSD to FASSDD (the ‘D’ in the new acronym is for deception). This change reflects a greater emphasis now placed on adaptation and deception in the new planning processes. Considerations for incorporating these aspects into planning are given at appropriate points throughout the new doctrine.

- More actions are continuous, and the process is more genuinely iterative. SMAP and JMAP were both explicitly non-linear, encouraging planners to revisit, remove, or change the sequence of steps to suit situational needs, but they contained very little that was designed to be continually updated. DMAP, on the other hand, specifies that commander’s and staff estimates, risk assessments, and critical facts and assumptions, all need to be constantly revised and updated. This is in addition to DMAP having enhanced the non-linearity of the process itself by expanding the explanation of how and when commanders should give directions to planning staff to abbreviate or skip steps. The outcome of this change is greater flexibility in process application, and increased potential for rapid decision making.

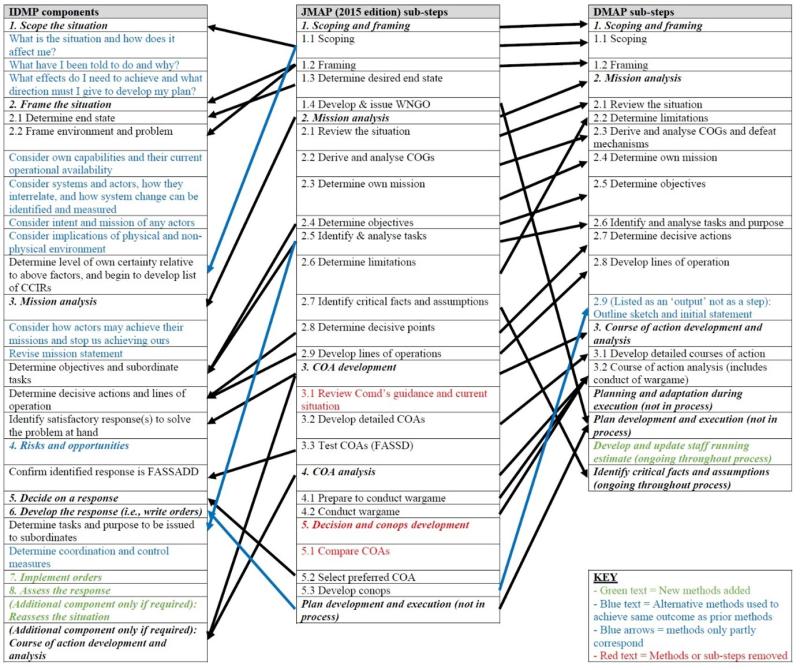

To aid in comparing the old and new planning processes, Figure 3 lists the JMAP steps (centre column), and indicates which IDMP steps (left column) and DMAP steps (right column) correspond to them. This diagram was produced by the author as an aide to assist in understanding the methodological and sequence changes between previous and current processes. Blue text in Figure 3 has been used to indicate where an alternative method has been used in IDMP or DMAP to achieve the same planning outcome as a previous JMAP method. Several (but not all) of these alternative methods came from SMAP or IMAP. As Figure 3 compares the new processes to JMAP only, these alternative methods do not appear to be linked to a previous process. This is not the case, and although these methods were not included in JMAP, many of them will be familiar to Australian Army personnel.

Figure 3. JMAP, IDMP and DMAP steps: method and sequence changes

VI. Further reading

A soldier’s five is useful for a quick orientation onto a new topic. It is not, however, comprehensive. The Decision-Making and Planning Processes doctrine publication remains the ultimate source of truth for all matters relating to the ADF’s new planning processes. Personnel who have not yet read the doctrine are encouraged to do so. It is available to download via the Defence Intranet.

A CoveTalk summarising the new doctrine publication and its development was given by the doctrine’s author, Major General Michael Krause, on 4 March 2025.

Parts of this Cove article are based on a forthcoming Australian Army Journal article by the same author, titled ‘A Central Pillar of the Army Profession: The Conceptual Evolution of the Australian Army’s and Australian Defence Force’s Operational and Tactical Planning Processes’. Readers seeking a more detailed comparative analysis of the new and old planning processes should consult this other article once it becomes available.

Thanks

Great question and well asked!