I had been serving as a seconded Military Officer within the Office of Military Affairs, Department of Peace Operations, United Nations (UN) Secretariat since Feb 2016. My principal responsibility in my first year was for management of operations in the Middle East, including Syria; however, in 2017 I was given wider responsibility. While conventional Department of Peacekeeping missions were the main focus for operational plans, but supporting military efforts for existing political missions was also a key role. This military support involved a team of military experts and advisors as well as guard units[1], to provide base security for UN compounds and office space in certain missions. This included guard units in Somalia, Iraq and a new requirement that required planning support – in Libya.

Background

The second Libyan Civil War of 2014-2021 followed the uprising and removed of Dictator Muammar Gaddafi in 2011 culminating in widespread French and UK strategic air assaults and a significant breakdown in the machinery of government and the security situation within wider Libya. The emergence of the General National Congress (GNC) in 2012 did not avoid on going internal conflict (rather it stoked the development of Islamic fundamentalists) and culminated in mid-2014 when the Libyan National Army (LNA) launched Operation Dignity – a large scale offensive against the Islamist extremists. In 2015, following a UN resolution and overwhelming UN support, the interim Government of National Accord (GNA) was established in 2016. This motion was internally disputed, primarily from the eastern populations of Libya by the LNA, commanded by General Khalifa Hafta.

General Khalifa is an American educated military officer who controlled the majority of national military power, as well as the majority of oil, ie wealth within Libya. Following the breakdown in the security situation in 2014 the United Nations also withdrew the support mission and re-located to Tunisia, pending an improvement in the security situation in Libya. In 2016 UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon endorsed planning to re-establish the United Nations Support Mission In Libya (UNSMIL). A principal compound was to be developed in Tripoli that would house hundreds of UNSMIL staff and support both the GNA and the wider rule of law within Libya. This account begins in early 2017 as the UN pushes to redeploy UNSMIL despite a further deteriorating security outlook due to Hafta’s LNA manoeuvring from the East to encircle Tripoli as the internal battle for power develops further.

My good friend and colleague from Nepal had been the lead planner throughout the second half of 2016. He had done a great job in conducting detailed site reconnaissance and analysis of the three broad location options that had been identified by the UN and Libyan interim Government. This would facilitate a secure move of permanent UN staff back into Libya (these staff had been based in Tunis since 2014). The complexities and risk considerations were wide and varied; however, it was finally decided to settle on a coastal expat village some distance from the centre of Tripoli. The guard (supplied by Nepal) was of significant size, with appropriate enablers (i.e., medical and APC) to maintain security and defend against a raft of potential threats. It had been force prepared by Nepal and was awaiting deployment. Unfortunately, delays (which are common in the UN system) had now delayed the deployment by six months to mid-2017. Additionally, the lead planner had to return to Nepal at the conclusion of his secondment to return to the Nepalese Armed Forces.

This is where I was called on to take up the role of lead planner. My first task was to attend the inter-departmental meeting with the Department of Political Affairs (DPP-A) and the United Nations Support Mission In Libya (UNSMIL), located in Tunis as an interim safety measure pending a return to Libya. It was very clear that frustration levels were high and a return to Tripoli was a highly expected outcome from the Secretary General (SG) down; however, the plans to return did not match the developing conditions on the ground.

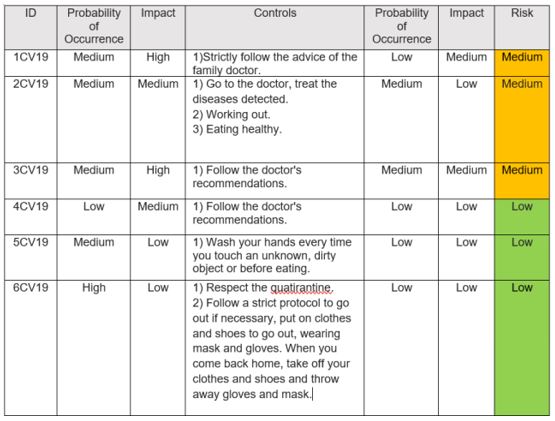

In explaining the risk profile for the new compound in Tripoli, a matrix was presented with all sectors being green (indicating either low or no risk attached to various environments within Libya). I rubbed my eyes to make sure I was not seeing things! I waited to gauge more senior officer reactions to this initial assessment. Unfortunately, it become clear that nobody was going to question the risk assessment, so when I was offered an opportunity to comment I had to question the methodology of the matrix. I enquired as to what specific planning had been conducted for the pending deployment of this unit? As I had suspected, the risk matrix was a self-serving assessment to support the deployment without delays. Balanced against the wide number of armed tribal groups within Tripoli and the developing conventional military threat emerging from the East (led by General Khalifa Hafta), the matrix really should have been a mix of amber and red. In answering to the Director, I did advise that significant risk mitigation and detailed planning could provide a reduced residual risk profile; however, it appeared that this planning was yet to be conducted.

I felt entirely justified about speaking up. The nature of the UN often means personnel work from short contract to contract, which can promote an overly cautious and unquestioning approach (where nobody wants to rock the boat and jeopardise the renewal of contracts). In my case, this was not an issue and it meant I got to say what many in the same room were thinking. The meeting concluded with action items, the first being that a team from New York would need to travel to Tunis and Tripoli to plan and coordinate the detailed deployment of the guard unit. Two weeks later, I was in Tunis with an interdepartmental team from New York and a Forward Recon Team[2] from the Nepalese Army.

I conducted an individual appreciation using the IMAP[3] and it highlighted a number of issues that needed to be addressed and a number that would remain both uncertain and largely unmitigated. The physical deployment, understanding of the compound and the development of contingency plans was something we could achieve. We conducted preliminary staff planning in Tunis before conducting a reconnaissance in Tripoli.

The biggest issue with Tripoli was that control (in a security sense) rested with varying personnel / factions / tribes / authorities depending on exactly where you stood in Tripoli. This provided a challenge in moving around Tripoli and even more importantly, for importing and moving high-end military equipment from the Tripoli APOD/SPOD[4] to the new UN compound. In normal circumstances, we would gain national customs clearances through the government of the day to enable this, but in this case it meant very little to the distributed power and control being exhibited across Libya. What we could control (to a certain extent) was to establish flexible and secure movement of troops and personal equipment from the APOD to the compound. This involved staggered timings (deconflicted with prayer and historical high-risk times), multiple routes and alternate routes through Tripoli, robust Command and Control processes, armed security and prior negotiation with tribal groups located on the deployed route.

To address our bigger concern, import approvals were sought and provided by the Government of National Accord (GNA)[5] via customs officials for the import of all weapons and a number of Armoured Personnel Carriers through the SPOD (National Port). This was, without question, our greatest risk to the deployment and an element of the plan that we had little way to control.

The reconnaissance into Tripoli was fascinating and reiterated the fact that control was going to be both difficult and unpredictable throughout the deployment. It would be essential to work up as many contingencies as possible to counter possible incidents. The choice of APOD was close to central Tripoli; however, more of a military facility than public which carried the risk that multiple stakeholders would be watching and might act – if it would serve a purpose. These stakeholders could be tribal or crime syndicates for example.

After clearing customs, we embarked on a high speed Military Police escorted road move through the suburbs of Tripoli. There are multiple roadblocks in place with armed rebel presence; however, we are able to move relatively freely along the approximately 20km route until we arrive at the compound. The compound was significant in size with over one hundred buildings and capacity to house over 500 personnel. The perimeter was bound by blast proof walls with makeshift guard towers constructed using multiple iso-containers and layered with sandbags to dominate approaches from all directions. The compound also bordered the Mediterranean Sea; however, with a rocky and turbulent water approach, the use of any watercraft other than Rigid Hull Inflatable Boats (RHIBs) was restricted.

We spent a number of hours walking the ground and testing the physical elements of mounting a defence to the compound. While the majority of defences had been completed to a satisfactory standard; a few minor alterations were requested by the Nepalese contingent. Some of the facilities (logistics hangars etc) were still under construction but seemed on track for completion. Of concern, there was an abandoned multi-story building approx. 300-500m from the compound that presented a direct fire threat from rocket propelled grenades. Additionally, mortar and rocket threats could be generated from either neighbouring land or sea approaches. Lastly, there was an established communications network and control room – physically central to the compound with local defence in depth.

Of note, the UN had managed to negotiate a 'support contract' with the local militia and this inferred not only logistical support – but a further degree of defence in depth as well. This was an essential component of the risk mitigation strategy; however, also not without its own risk. This risk included creating an expectation of an on-going, 'negotiable' contract that could see the UN exploited for exponential financial gain, balanced against unacceptable threats that would prevent the execution of mission's mandated programs in Tripoli.

Also of note, the Secretary General had engaged former USG DPKO Jean-Marie Guéhenno from France to conduct a wider Strategic review and assessment of UNSMIL in parallel to my reconnaissance. I was to be interviewed by Mr Guéhenno for about an hour (as part of his formal review) to discuss the military elements to the mission’s mandate and plans to deploy a guard unit. Guéhenno had just returned from Benghazi, where he had met Hafter and remained very cautious of a UN return to Tripoli; however, was most interested in a layering of mitigation options to specifically address the full range of threats the mission might face, including from the Mediterranean via small coastal vessels delivering indirect fire.

Over-arching context to the deployment

There were potential risks in conducting this deployment and some of those risks could not be mitigated. Ultimately, the execution of the plan could result in a number of untidy results. Furthermore, even if we were successful in deploying the guard unit – would they have an acceptable contingency plan to evacuate under extremis conditions? Our analysis and incidents at the SPOD, APOD and coastal road to Tunisia indicated that a worst-case scenario would be unmanageable. Cross talks with neighbouring nations and NATO/EU bodies outlined potential maritime options to evacuate; however, resources would need to be assigned that could not be financially supported. Alternate options were also explored, including analysing the time, space and capacity of the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) Maritime task force to sail to the extraction point and evacuate by RHIB.

How it played out

The full complement of the Guard, personal kit, weapons and some stores arrived at a military airport in Tripoli late in 2017. The processing of customs clearance for personnel and their kit went smoothly, as it did for most stores. Just when it appeared that the whole activity would proceed without incident, a new group of Libyan personnel arrived on the scene and advised that they were taking the 84mm anti-armour weapons and ammunition to a separate hangar to be independently inspected. Identifying this as a clear opportunity to take these weapons, the contingent refused this. In fact, the senior military advisor to UNSMIL (a 3 star Italian officer who had previously commanded UNIFIL) took to physically sitting on the pallet to prevent it being taken.

This stand-off was maintained for nearly eight hours while staff in New York searched for options to this problem – fortunately the contract aircraft had not yet taken off – and it was quickly re-contracted to re-load the contentious cargo and fly it to Beirut – where it could be secured with a Nepalese contingent in UNIFIL.

In parallel, the APCs arriving at the civilian port also 'disappeared' until the UNSMIL chief of mission support was able to physically track down and provide incentives to 're-acquire' the containerised vehicles and move them by truck to the UN compound. Fortunately, all vehicles were quickly recovered. Losses of attractive smaller items like GPS, knives and personal items however were not recovered.

The three convoys of multiple vehicles to move the contingent from the APOD to the compound was executed without incident. This demonstrated that the risk of most concern is generally the one that does not eventuate.

So what are the lessons here for a prospective ADF Officer keen to serve in the UN?

- Have the moral courage to speak up when something does not look right – an easy option is to be a sheep and follow the flock. I would like to think that this is how we train our young leaders in the ADF, but passive 'yes' and 'follower' cultures can be prevalent, even at senior levels.

- Physically walk the ground – get multiple views (images and pictures are a poor second to physical recon) and consider all possible eventualities when developing your COA, even if there are eventualities that you cannot control or mitigate.

- Develop 'actions on' and contingency plans in detail - these plans will consume your time and span Tactical, Operational and Strategic/Political effects and options.

- Try to understand organisational and cultural differences to planning. What might work for a civilian based organisation might not work for the military. Test those boundaries with constructive cross-organisational dialogue and remember you have to work together on this and the military is the supporting effort – not the supported!

- Ensure the plans are developed as a team and fully communicated to all stakeholders – trust the force elements to execute the plan as agreed.

- Embrace any opportunity to work with the Defence Force of another country. For example, I would speak very highly of my interaction with the Nepalese Defence Force. Their officers and soldiers were intelligent, disciplined and great team players. They made my plan work.

Overall, this was a successful deployment to a volatile and uncertain environment which set the conditions for wider civilian deployment under the political assistance mechanism. Libya was then, and remains today, a highly complex operational environment, further complicated by the resurgence of ISIS cells and continued in-fighting by various tribes and factions within the country.

UNSMIL remains one of the few organisations trying to deliver meaningful projects of impact to restore effective machinery of government to Libya – for the people of Libya, I remain hopeful that reform is achievable in the not too distant future.

UN Compound in Tripoli.

Good article but you are wrong in one are: the UNSMIL camp was not new: it was established and occupied when you took up planning. It was already fitted out with a reasonable degree of security, which was later enhanced, and the necessary logistics to allow us to live there as I have done on and off since August 2013.