The way in which we deliver orders at the tactical level is key to communicating the plan and achieving mission success. In the age of PowerPoint and OPORDs (operational orders) of intimidating thickness, it is sometimes easy to forget the end user of these products. It is often that the higher level orders will cascade and be extracted down the chain of command until it reaches the ears of a tired digger and they hear their small part in that much larger plan.

The delivery of orders at the tactical level is not often given enough attention. Sure, we ensure that our junior leaders understand SMEAC [i] during promotion courses and we ensure that they tick off each planning consideration to guarantee that their plan is tactically sound. But what we sometimes neglect to focus on is the way in which these orders are communicated to a subordinate who could be fatigued, nervous or both.

It has been a common observation, in my experience of receiving and delivering orders, that outside of promotion courses and assessed exercises, many tactical commanders will ignore the one third [ii] planning time and not factor in time for the delivery of orders during their planning appreciation. Time to deliver your plan, and allowing your subordinates time to do the same, is essential.

Communicating the intent

Slim believed the ‘intent’ was the most important part of any set of orders:

'One part of the order I did, however, draft myself – the intention. It is usually the shortest of all paragraphs, but it is always the most important, because it states – or it should – just what the commander intends to achieve.'[iii]

If, like me, you subscribe to this then it is conceivable to believe that a strong delivery of orders allows the commander to give their intent the emphasis and explanation that is required.

Selling the plan

There are many examples of historical leaders delivering orders for a plan that sees the force facing overwhelming odds or facing a situation that may see significant risk of casualties.

For instance, GEN James Mattis, commander of the 1st Marine Division during the Battle of Fallujah, was ordered to give the halt and withdrawal from the city, despite the cost in lives and terrain that had already been paid. He said in an interview conducted in 2016 [iv] that it was the toughest decision he had to make in his time serving in the United States Marine Corps. It is in moments like this that the commander delivering their orders must also deliver the moral component of leadership and make their subordinates believe in the plan set before them and understand why they need to do it.

Whilst it was a decision Mattis was ordered to make, the delivery of that order was what has set him apart and made his subordinates, at the lowest level, trust his leadership and command.

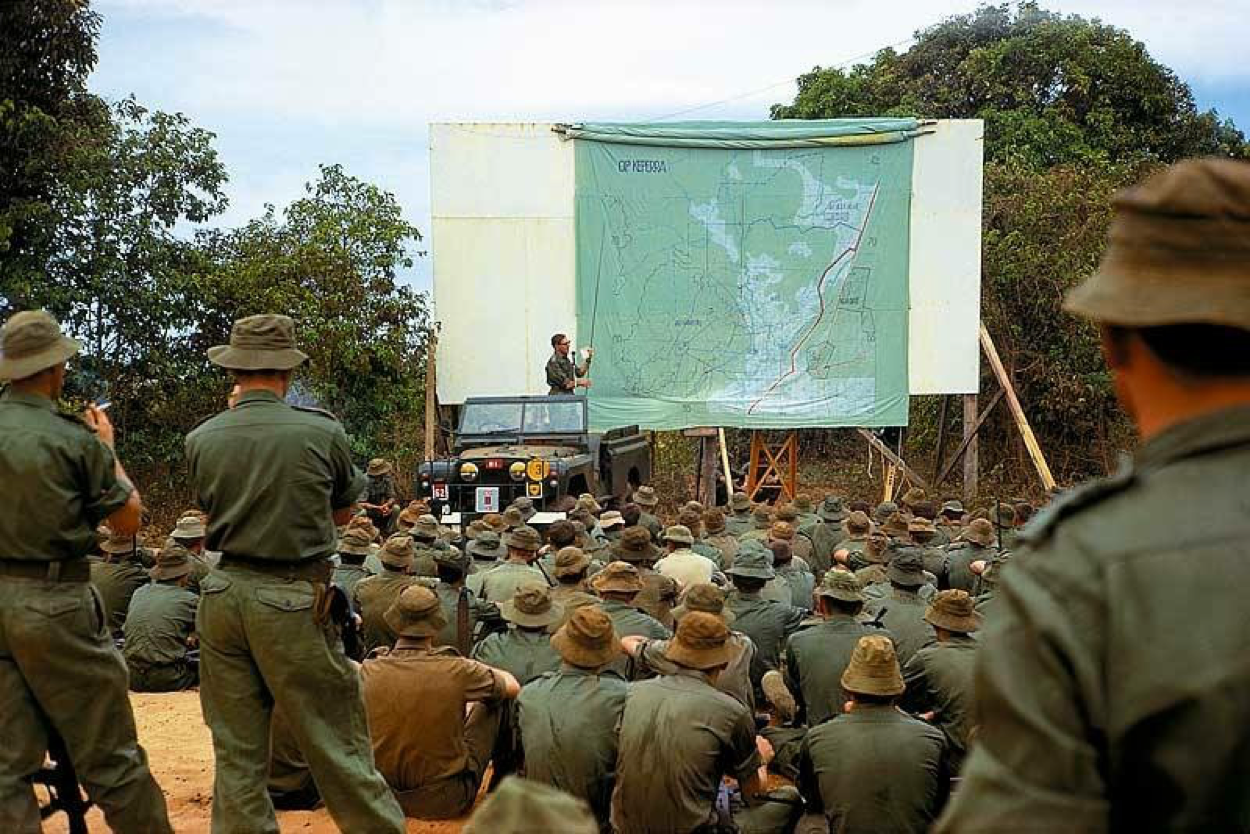

Painting the picture

The ‘bonnet brief’ or ‘map brief’ has become the favour of the lazy commander. It does not always allow for subordinates to understand the tactics and coordination of a plan, in time and space. Where time permits, and for a deliberate action, a mud model is an excellent stage hand to a tactical commander. Even in a hasty situation, the power of a sketch map during a quick attack should also not be ignored. Allowing your subordinates every opportunity to visualise your plan and share your understanding and intent cannot be overestimated.

Delivering orders at the tactical level is a human endeavour. It is an exercise in convincing other people to carry out your plan and, possibly, put their life and the lives of their subordinates in your hands. It is, more often than not, something we do at the dead of night, when our subordinates are tired, hungry and feeling the effects of the climate. This confirmation can be a full rehearsal of concept (ROC) drill, if time permits, or as simple as confirmatory questions to subordinates on your intent or their part in the plan.

The verbal delivery, mud model or sketch and ROC/confirmatory questions allow the commander to address all 3 types of learning style. Auditory, visual and kineasthetic [v] learners can then all be catered for.

A confident delivery of a set of orders and looking at the recipients in the eye can also give you, the commander, the reassurance that your plan is understood.

Conclusion

Command is the authority to deliver the orders, but it is leadership, derived through your delivery, that ensures your subordinates understand those orders and, more critically, want to follow them with the appropriate levels of passion, aggression or patience required for that task