'But the LORD said to Samuel, 'Do not consider his appearance or his height, for I have rejected him. The LORD does not look at the things people look at. People look at the outward appearance, but the LORD looks at the heart.'

– 1 Sam 16-7 (NIV)

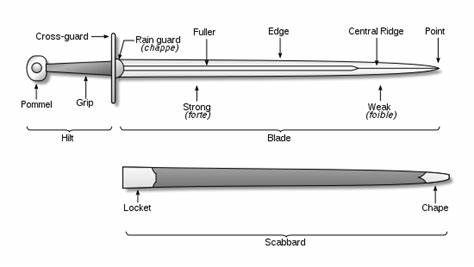

Apart from attending the chapel at Kapooka I didn’t have much to do with chaplains as a young soldier, but I do remember being unimpressed with what I saw. The image of the chaplain at Singleton looking like he was under the weather; smoking and swearing, triggered a judgmental attitude that prevented me from seeing the value of a man who had served in Vietnam and who today, I would warm to as a son to a father. Several decades later I would struggle again with a critical attitude towards chaplains, many of whom were now my colleagues. I struggled with the quirkiness I observed. Quirky means a peculiarity of character; mannerism or foible. Foible? It means much the same as quirky; a slight peculiarity or minor weakness; idiosyncrasy. Foible also describes the most vulnerable part of a sword’s blade. Foible now had my attention, and this in itself reveals a peculiarity.

Wikimedia Commons / Nathan Robinson of my.Armoury.com

Without the foible the sword has no point.

The effective use of any weapon system requires familiarity and competency. The operator must know its capabilities, its limitations, and how to apply all of these skills under arduous conditions. The same applies for people. Every person has a foible or two; knowing this is the first step in developing self-awareness and the skills necessary for emotional and social growth. In like manner, the good leader intuitively applies a combination of the same skills to achieve cohesion in order to attain an outcome. Every leader and every team has within it a peculiarity of character, a combination of strengths and weaknesses that are unique to the individuals who make up the whole. Chaplaincy is a quirky part of the military team and for many personnel, the chaplain is an enigma; well explained through the parable of the blind men and an elephant.

A group of blind men heard that a strange animal, called an elephant, had been brought to the town, but none of them were aware of its shape and form. Out of curiosity, they said: 'We must inspect and know it by touch, of which we are capable'. So they sought it out and when they found it, they groped about it. The first person, whose hand landed on the trunk, said, 'this being is like a thick snake'. For another, whose hand reached its ear, it seemed like a kind of fan. Another, whose hand was upon its leg, said, 'the elephant is a pillar like a tree-trunk'. The blind man who placed his hand upon its side said the elephant, 'is a wall'. Another who felt its tail, described it as a rope. The last felt its tusk, stating the elephant is that which is hard, smooth and like a spear.[i]

The parable illustrates how one person’s subjective experience may differ from another, causing them to draw different conclusions. A similar scenario could easily apply within Defence if a select group were asked to explain what a chaplain does. Appreciation of chaplaincy, or lack of, is mostly influenced by subjective experience. In this article I will reflect on my own experience as a Defence chaplain and propose that it is who the chaplain is that best defines what they do. I wish to shine a light upon certain facets of chaplaincy that provide insight into the mystery of, 'What do chaplains do?'. I have deliberately called it a reflection, as opinions amongst chaplains will differ on the many topics covered. In doing so I hope to achieve two aims: the first, to encourage chaplains in what it means to be positioned to serve, and secondly, the hope that others in uniform may be enlightened by the foibles of chaplaincy.

The issue of the chaplain’s identity is at the centre of this discussion. Some years ago, Dr Gerald Gleeson, guest speaker at the chaplains’ regional seminar stated, 'The rejection of Christendom is a rejection of identity'. Dr Gleeson explained that 'No-one believes in grand narratives anymore. The secularisation of society represents a major shift in narrative, from creation’s story, redemption… to a collapse of grand narrative. Gone are the stories that once grabbed people’s attention and inspired their imagination, stories that helped people interpret their lives and answered their questions, sin, redemption, salvation, the story of good news, a narrative that has now become meaningless and irrelevant.' Dr Gleeson’s insights into Military chaplaincy in the 21st century was equally relevant:

Chaplaincy has undergone a major shift in understanding its place and purpose. Chaplains are busy at the tactical level; they thrive at the coal face interacting with soldiers where most of their work goes unseen. In the past the chaplain’s position was based on relational trust within the organisation, based on a clear history of the clergy’s role in society. But this is no longer the case and much of Command, particularly at the tactical level see chaplains as discretionary; they float on the edges in an uncertain world where trust has been transferred to systems and processes.[ii]

I can relate to the statement 'floating on the edges in an uncertain world'; at times feeling invisible in a system that questions my identity. I have also experienced the best of what chaplaincy offers to Defence and I believe that trust is still our primary currency; however, it cannot be taken for granted. Like the chrysalis emerging from the cocoon, the process of wrestling with issues of identity is necessary for the development of what is to form. Dr Gleeson’s challenge remains, 'How do we as chaplains who represent such a grand narrative, connect with soldiers and officers who have no idea what our narrative is?' The key to my service as a Christian chaplain is my religious identity.

The understanding of my religious identity as the key to my effectiveness as a chaplain came as a revelation through the teaching and leadership of Monsignor Glynn Murphy. In his role as DGCHAP-A, Glynn framed chaplaincy within three pillars, or 'Hallmarks', as he called them; the religious, spiritual and pastoral. Prior to this I was a chaplain who happily stated that I was spiritual, not religious; a cliché well received but revealing much about my lack of insight and experience. Thanks to Glynn I can confidently say I am religious, but I’m not very good at it. In Glynn’s words, as I recall them, 'The strengths of the Hallmarks are evident in their application to any faith group and the provision of a legal (for army), moral (for each chaplain) and ethical (position within army) framework for chaplains to understand and communicate what it means to be an army chaplain. The Army requires these three of its chaplains because no one else in Army is required to have these qualities.' I include the Hallmarks below:

- Religious: The external expression of the spiritual beliefs (Divine revelation), doctrine and teachings within a faith community, within which the chaplain is a member/leader and which publicly endorses the chaplain for Army service (through Religions Advisory Committees (RACS)).

- Spiritual: Belief in the reality of God as creator, author of life, ultimate meaning behind life for all people, belief in the reality of eternity, belief in the eternal soul of each person, and belief in the consequences of the above.

- Pastoral: The ministry lived in a deliberate and continuous manner for others, generating from the belief in spiritual realities and what those realities demand of the individual Chaplain, by life publicly given to pastoral and other service ministry.

The Hallmarks defined chaplaincy for me and reinforced that my identity is not based on an ideology or even a set of beliefs, but in the person of Jesus Christ; not as an historical figure but as the living God, 'the incarnation of God with us, alongside others'. Glynn’s contribution to the emerging place and purpose for chaplaincy (in Army) was a great help to me, reinforced by the message that it is the call of God on my life that provides the authority to serve; an internal conviction that should underpin my motivation. Why is this 'authority' so powerful a motivator? Because it is not of the natural, it is of the Spirit of God and bears witness within my spirit, not as an area of my life that can be externally seen or proven to Army, but reflected in my character. My authority as a minister of the gospel (good news) comes from Christ through my sending church, and as a military chaplain I am in effect 'on loan' to the Australian Defence Force (ADF). For this reason, first and foremost, I serve God and then I serve under the authority of my designated CO. This dual allegiance sheds light upon why chaplains serve both in the chain of command and outside of the chain of command.

In contrast to the secular attitude that may interpret the chaplain’s religious identity as grounds to limit their service, I believe the foibles of chaplaincy, far from being a weakness, add a strength to the military system; drawing upon a long and proud history in the ADF. And, like all institutional organisations, chaplaincy continues to evolve and adapt to its environment. ADF Chaplaincy, represented by the Religious Advisory Committee (RACs) is now a multi-faith service, with members from the Muslim, Buddhist, Jewish, Hindu, Sikh, and Christian traditions, serving together to ensure all service personnel and their families, regardless of religious affiliation, have access to chaplaincy support.

As a chaplain, it is not my religion that is of most value to command. Command knows that religion has its place and its importance to those who adhere to its beliefs is well respected and protected. My value to command is in the care I provide to the soldier (I use the term soldier in a generic form to refer to all Defence personnel who serve in uniform). I am one of many specialists who work to ensure our soldiers are physically, mentally and spiritually healthy to serve their nation. But as the Hallmarks of chaplaincy highlight, only the chaplain is employed to care for the religious, spiritual and pastoral needs of the soldier and their family. To this role the chaplain brings something uniquely shaped by the formation of their character and personality, underpinned by their belief in a divine calling to serve.

In response to the conviction that God has called me to serve, my actions are supported by a pastoral theology that defines why I do what I do. My motivation for service is not based on any form of law or contract but on the love and grace of God as demonstrated in and through Jesus Christ, and sustained by the presence and power of the Holy Spirit. My worldview is shaped by a Judeo-Christian tradition and a biblical belief system that recognises that all people are created by God, loved by God, and have equal value, worth and dignity, regardless of race, religion, gender or status. My actions are an extension of my beliefs, demonstrated in the care of soldiers and their families, given without judgement or partiality. My service is never conditional upon soldiers believing or even accepting my beliefs, but upon their value and worth as a person.

The life and ministry of Jesus as recorded in the Bible is the example the Christian chaplain endeavours to follow. How this incarnational ministry translates in my life is worked out every day, in my failures and successes and everything in between. In order to explain my pastoral theology, I have drawn upon the ministry roles that Christ fulfilled as prophet, priest and king, under the call-sign of Shepherd. The chaplain’s prophetic role emphasises the ability to speak into the lives of soldiers and illustrates a proximity to power and authority. The priestly role helps me understand the sacred and spiritual dimensions of life, as well as the religious, and the kingly role exemplifies my presence as a chaplain, creating peace and calm. Chaplains of different traditions have much to offer in their interpretations of these roles and like our blind friends describing the proverbial elephant, my experience is limited.

Call-sign shepherd

The image of the shepherd speaks of identity, reflecting the language of vocation, rather than career. The Great Shepherd Jesus is the one who calls and says, follow me, feed my sheep. When true to my calling, I have little time for the politics of personal ambition and seek no place of position or power; my rank is that of servant. As a former soldier I no longer wear the uniform as part of the profession of arms. Instead, the transition from warrior to priest reminds me that as the shepherd, I am not one of the sheep. I am called to serve as one set apart, so when the system looks at me, the chaplain, it should not see a reflection of itself, as one looking in a mirror. I experienced a powerful reminder of this recently while participating in a ceremonial service. As the Colours passed I stood not at attention as all soldiers must, I am not required to salute (in my priestly role), because the chaplain is set apart, sanctified, as are the consecrated colours; a reminder of past traditions embellished on our insignia, reminding all that the cross is positioned above the crown.

As the shepherd, my influence and effectiveness must be established upon relational trust. If I am only a service provider, the interventionist who sees a soldier by appointment, trust is secondary to my role. Traditionally the shepherd lived with the sheep and shared their privations. In the same fashion, I am embedded into the unit and life of the soldiers I serve. My role is characterised by humility and compassion, which speaks more of attitude than position. Such an image, however, can be misleading as the shepherd is also a leader and protector of the sheep, requiring courage and resilience. As part of a given command structure I must work to create unity (teamwork) knowing that if I isolate myself from command or soldiers the team is weakened. My ability to be a team player is in direct proportion to my ability to build relational trust; from the nervous private who has just marched-in, up to the CO and beyond. A mixture of personality and experience working together, transforming my job specifications into influence and distinguishing the shepherd from the hireling.

Like a general practitioner, the chaplain’s specialisation is pastoral care. I am yet to hear a commander say they wish I would spend more time doing administration or working on my computer producing spreadsheets. These are important and necessary tasks. Defence employs a lot of people with competent administrative skills but has limited specialists whose primary role is pastoral care. First principles demand that the shepherd is motivated by their care for the sheep, but as someone once said, if you don’t like the smell of sheep you shouldn’t be a shepherd. The stressors of the military system, constant complaints and negativity, as well as a myriad of sad issues become part of the shared experiences that shape the life of the shepherd. It follows that if I am not motivated by compassion for those I serve, I should seriously question if I am in the right paddock.

To be positioned to serve I am empowered with freedom that few others are granted; freedom of movement, freedom of action and freedom of time. Each of these freedoms is necessary to be able to function within and outside of the chain of command, bypassing reporting lines when necessary, offering flexibility to schedules or participation in training programs and activities. Such freedoms are necessary to function in the grey areas of policy and procedure, for the purpose of serving the soldier, advising command, and building a strong command team. They are each an extension of the trust given to the shepherd, carrying a responsibility that requires a deep understanding of the soldier and the military system.

The shepherd’s prophetic role

The personality of the chaplain is intricately entwined with their role and even enhanced by distinctive quirks or foibles. The chaplain is empowered to exercise freedom of movement, action and time for the purpose of caring for soldiers. In their book Practical Theology in Action, Ballard and Pritchard reinforce the principle that the chaplain should, 'sit loose to all human institutions, having a prophetic freedom and a primary responsibility to truth and justice'[iii]. There is little room for individuality in an organisation that demands conformity and uniformity unless the system applauds it or empowers it. Take the larrikin for example; loved and despised yet tolerated, because humour humanises the system. In like manner, the chaplain is something of a maverick within the chain of command; free to challenge the system and push the boundaries. Such freedom requires a clear understanding of why such a role exists and how it should be used.

The chaplain’s prophetic role describes the responsibility of speaking into soldiers’ lives and into the chain of command. Ballard and Pritchard provide an interesting insight into the chaplain/command relationship based on the role of the court jester: 'The court fool is both a favourite and a butt, sitting at the King’s counsels yet alone and marginalized. It is not the easiest role to play'[iv]. The court jester exercised a freedom within the King’s court that required great skill. He held no official role in the ranks of the court and could say what he liked, usually to amuse the King. His humour could be used politically against the King’s opponents as well as to challenge the King’s authority, with tongue in cheek. However, the jester risks his head should the King take offence. The CO is the ruler of their kingdom and like the court jester, the chaplain has unprecedented access to his/her presence. Theirs is an exclusive relationship, built on a dynamic of trust, like an RSM, but equally diverse.

The chaplain’s prophetic role embraces the tension of being in a military system, belonging but not belonging[v]. Such a position will challenge the identity of the chaplain and questions their motives. A trusted friend once confronted me with the question, 'Ren, who do you serve?' I knew the answer wasn’t God, and as I suspected, it was not a question. My answer, 'I serve my Commander', was quickly corrected with the reply, 'You serve the soldier.' I wanted to argue that yes, that is correct, but I also serve command and everyone in the chain of command. Text book answers mean little to my friend, who has a gift for exposing my vulnerabilities. He wasn’t challenging my thinking but my motivation, and revealing my fear of confrontation and desire to please others.

The valued lesson I received reminded me that part of my role and calling is to defend the weak and the powerless. In the military this is the private soldier who relies upon leadership for direction and protection. Good leaders motivate and inspire good soldiering, but when leadership fails, or when the problems the soldier is experiencing are related to their chain of command, where then does the soldier turn? What if they are ostracised from their mates or feel victimised and bound by fear? If the chain of command believes it is right and the soldier is wrong, a power imbalance leaves the soldier feeling helpless. It takes courage to stand up for the powerless, the disadvantaged, or the abused, and be their advocate. The system must have a voice and that voice may need to challenge the chain of command, it may need to confront the powers that control the system and courage must come from conviction.

Without an understanding of their prophetic voice the chaplain risks functioning like a subordinate. When my motivation is to serve command based on seeking approval and acceptance, I may succeed in getting a good PAR (Performance Appraisal Report) but will have failed the soldier. The prophetic role reminds me that I am called to speak the truth, well-illustrated by MAJGEN Chris Field, 'A chaplain who is mentally strong and morally confident is able to deliver tough advice; not only to people who need a change, but also to unit leadership, including the commanding officer. A tough chaplain with moral fortitude and courage will save lives. No unit can ask for more from their chaplain'[vi].

The shepherd’s priestly role

Some years ago, I shared with a lecturer of my difficulty concerning the issue of quirkiness and was encouraged to seek greater understanding of my priestly role. Because of my Baptist upbringing and influence as a Churches of Christ minister, I struggled to see the connection. In due time I came to see that my priestly role as a chaplain was bound up in my religious identity, which connects me with the spiritual dimension of life from which meaning, purpose and identity are centred. I am thankful for this older man’s wisdom and so began a deeper appreciation of the foibles of chaplaincy. I have since learnt that any form of quirkiness in an individual is a strength when the heart is characterised by integrity and authenticity. As mentioned earlier, the issue of my identity as a chaplain is critical to my ability to serve effectively.

It is my spirituality, shaped by my religious formation and experience that grounds me in order to communicate with command and soldiers. Rather than religion being a barrier to effective communication, it provides a depth and richness to draw upon, which empowers trust and confidentiality based not on policy, but on respect for the sacredness of the soul. For a soldier to bear their all, to be emotionally vulnerable, or to confront their fears, requires an intuitive knowledge (faith) that their trust will not be abused. In the same way, when my relationship with command/authority is based on the security of my identity and the conviction of my call to serve, I am free from the influences of the system that control the motives of its personalities.

My identity as defined by the religious Hallmark, empowers the priestly role to understand the spiritual nature of those I serve. This is particularly relevant in an age when religion and spirituality have taken on contrasting definitions. In his book, The spiritual revolution: the emergence of contemporary spirituality, David Tracey provides insight on how religion and spirituality are presently understood outside of the church, stating: 'Spirituality seeks a sensitive, contemplative transformative relationship with the sacred, and is able to sustain levels of uncertainty in its quest because respect for mystery is paramount'[vii]. From Tracey’s perspective spirituality refers to the relationship with the sacredness of life, nature, and the universe; an inclusive term, covering all pathways that lead to meaning and purpose. The soldiers I serve may care little for such definitions, they do; however, reflect the attitude of the times and within the priestly role, the chaplain is a moral authority who represents the sacred; a figure largely missing from today’s collective conscience.

The transformative relationship with the sacred, to borrow Tracey’s words, surface when the deeper issues of the soul, like life and death or grief and loss, interrupt our illusion of control. At such times, command becomes aware of its limitations. It is the priestly role that allows the chaplain to communicate the power of presence, to bring comfort, peace and hope. I would never force my religious views on others unless asked out of genuine interest, but through my priestly role I represent the sacred and spiritual to those in need. I have lost count of the number of notifications, funerals and other sad events I have dealt with, but in my priestly role, I know the value of silence and the wisdom to know that, 'presence to the pain of another does not require that we provide a solution'[viii]. The silence of the last post moves me deeply having experienced the loss of soldiers killed in conflict and reminding me that life is sacred.

I see my priestly role within Defence as a remarkable privilege, bridging the civilian and military divide, whether presiding at weddings, baptisms, funerals, civil or religious services. The confusion over that which is religious or spiritual is a constant reminder that soldiers have always been irreligious and will do their best to avoid the 'god botherer'. But I have met very few soldiers who do not have an appreciation for the spiritual and are usually keen to discuss such issues, along with politics and religion.

The shepherd’s kingly role

Former Anglican Bishop to the Defence Force, Tom Frame, reminds us that until recently Christianity 'shaped the moral culture' of Defence, making the role of the chaplain an extension of the church’s ministry[ix]. Dr Gerald Gleeson’s analysis that 'The rejection of Christendom is a rejection of identity', also reminds us that chaplaincy is still working through a crisis of identity. The days of the Shepherd being the moral compass within Defence reflect the assumption that all institutions are inherently idolatrous, a claim that various commissions into institutional abuses has justified[x]. As a moral authority figure I draw upon Christ’s kingly role to understand the importance of leadership and authority. This area of the chaplain’s identity is often the most neglected and is critical to my own sense of belonging within Defence. With no delegated authority to command, my role as a leader is primarily exercised through influence and addresses the prophetic role of speaking into lives and situations, as well as by physical presence. As call-sign Shepherd, I am a leader and need to know how to act as a leader within Defence. Defence expects the competence that it pays for, but I often struggle within a system that rewards competitiveness and ambition, challenging my sense of identity.

Defence acknowledges the spiritual/moral component of the soldier through character development, but particularly in the moral component of warfighting. For this reason, the chaplain is the subject matter expert in character development; a critical part of the profession of arms, not only for the training of leaders but because the role of the soldier is unlike any other within society. The lawful killing of other human beings often has a catastrophic effect on the soul of a soldier and impacts families with equally destructive consequences. When the shepherd functions as a leader, their influence is felt from the lowest soldier to the highest command, reinforcing what Defence has always practised, but often failed to acknowledge that: 'the missing link in character, resilience and leadership is the spiritual dimension'[xi].

Knowing the value of my role within the system builds confidence, even at those times when I may feel invisible. As a leader I draw upon my knowledge and experience to intuitively know what to say and when to act. Through pastoral care my presence can bring peace to troubled souls, calm to stressful situations, hope to those who despair and comfort in loss. Within the chain of command my 'prophetic' input provides balance to a system that can easily forget that people are our greatest asset, people who have families that pay the price for our service. Through religious/spiritual care I speak into lives concerning the issues of identity, meaning and purpose, impacting career decisions and providing guidance. And within the religious space, the priestly ministry continues to provide a service that no one else within Defence can deliver.

Conclusion

This article has argued that the foibles of chaplaincy provide a strength within the military system that are unique, described through the biblical types of the prophet, priest and king, under the overarching banner of Shepherd. As chaplaincy continues to adapt and evolve in order to serve Defence, my hope is that the foibles of chaplaincy will not be sacrificed on an altar of professionalism, reflecting the system it serves. This is a challenge not only for the chaplain who has come from the ranks, but an ongoing challenge for all who work to shape the future of chaplaincy.

'Now the God of peace, that brought again from the dead our Lord Jesus, that great shepherd of the sheep, through the blood of the everlasting covenant, make you perfect in every good work to do his will, working in you that which is well-pleasing in his sight, through Jesus Christ; to whom be glory for ever and ever. Amen.'

Hebrews 13:20-21

I especially appreciated your comments on:

- the importance of trust

- serving the soldier as being the primary focus of the chaplain's role (and not being preoccupied with approval and acceptance)

- navigating the tensions of having a unique place in the chain-of-command and not hesitating to speak prophetically to soldiers and/or Command.

You helped me think more about how to sensitively and confidently bring a chaplain's contribution to religious care, broader pastoral care and character development.

#positionedtoSERVE