The Combat Tracker Team provides a surveillance agency that cannot be replaced by any other means in the terrain conditions that exist in SE Asia. If the Combat Tracker Team is skilfully employed against the Viet Cong, many lucrative targets will be acquired for destruction by our air mobile infantry and their supporting fire power.

– OC Tracking Team, 1968.

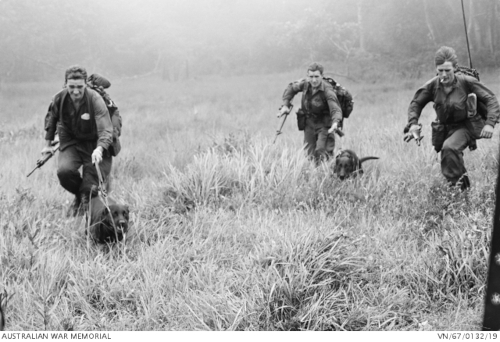

The Australian Army has a proud history of using single purpose tracking dogs during the Vietnam War. Other militaries have also used tracking dogs with great success; the British pioneered their use during the Malaya and Borneo campaigns, and those positive experiences were the inspiration for the US and Australian use of Combat Tracking Teams during the Vietnam War. Training notes made by staff at the Australian Infantry Centre in 1968 note that Combat Tracker Teams, consisting of both visual and canine trackers, were the only effective weapon for pursuing the VC into areas they felt safe in due to a lack of other methods which could track enemy movement (Australian Infantry Centre, 1968).

Whilst unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and robotic process automation technology has gone a long way to increase our ability to track enemy movement remotely, having eyes in the sky 24/7 exactly where needed is currently not realistic, and there are limitations of what can be seen through thick jungle canopy or building rooftops. There exists a current in-service tracking capability, held by Army’s Military Police Dogs (MPD) and Combat Assault Dogs (CAD); however, they are not selected or trained for long distance tracking (15km +) of heavily aged tracks in complex terrain. Only a dedicated tracking dog capability offers these force protection and offensive options that do not exist through any other means.

Visualising when you might need a tracking dog capability

Here are two hypothetical scenarios based on real life events:

You are patrolling through close jungle terrain when your platoon comes under small arms fire. After reacting to contact and conducting a quick attack on the enemy position, you move into the reorg phase. During the reorg, it is identified that there are several visible tracks that show several of the enemy have withdrawn.

Given a fast-moving person can easily travel over 7km in an hour, any pursuit will be a nerve-wracking and risky endeavour as at any time the now highly alert enemy may be laying in ambush awaiting your follow-up. Instead of moving out immediately, you radio for a tracking dog team. The team are flown in and winched into your harbour. They immediately get to work and pick up the trail. After tracking with your call sign in tow for over 2 hours, the dog shows sign that it is close to the enemy. The visual trackers confirm there are four enemies likely only carrying small arms.

After moving forward more cautiously, the handler informs you that the dog is offering a triangulating alert and gives you a bearing to where the enemy is most likely. You put in place a support-by-fire position and manoeuvre the rest of your call sign in a flanking movement. You surprise and destroy the enemy in place as they lay in ambush covering the direction they had just come from.

Alternatively, during a company level cordon and search operation, you come under fire from a second story window as you clear through a built-up urban environment. You have your platoon immediately assault forward and clear up to the room from which you were fired upon. The enemy is gone; however, you call forward the tracking dog team attached to your combat team.

The handler identifies a scent article for the dog to use to track the enemy combatant. After taking odour, the dog follows it outside and through streets and alleys. After tracking three more blocks, the dog gives a strong proximity alert as it tracks down a deserted street. The handler relays this back, and you send a clearing patrol forward. The clearing patrol identifies a substructure entrance that has been kicked in. A clearance is conducted, and an unarmed individual is located hiding in a cupboard. They are detained and handed over to partner force police for processing.

What is a single purpose tracking dog?

Single purpose tracking dogs are trained only for tracking a designated human odour. They typically have no capacity for engaging a threat through biting, as the traits which make a dog capable of tracking for up to 15km, are not often found in a general-purpose dog that is used for both tracking and apprehension. Breeds often found most suitable for tracking include Labradors, Bloodhounds, Plot Hounds, and Hanoverian Hounds amongst others.

The tracking dog offers the ability to pursue enemy forces at speed in a much safer manner as the dog can provide early warning of approaching an enemy threat through its body language on the track as it detects the scent pool of the enemy. This is something visual trackers are unable to do. A tracking dog is a force multiplier in that a well-trained handler and dog can detect ambushes at a distance and gain ground rapidly on fleeing enemy forces whilst simultaneously minimising the risk of being taken surprise as friendly forces get close to their position.

A tracking dog is patient and can stay on a single odour over incredible distances. They are trained to track on any surface from the jungle floor to the urban jungle. They are driven to track, without over-the-top agitation (Schettler, 2013, 4). Importantly, the dog needs a handler who understands scent theory and how it is impacted by age, weather, temperature, wind, and contamination from other odours – all in real time as they handle the dog. Working together, a well-trained tracking dog team will be able to provide an unmatched ability to pursue a wanted subject.

Contemporary use of tracking dogs

In recent times, the US Army used tracking dogs during Operation Iraqi Freedom to hunt for improvised explosive device (IED) makers that supplied the insurgency with the tools to kill and injure US troops. Any time wasted in getting tracking dogs to the source of a scent was understood to be a handicap for their ability to trace the minute particles of skin, hair and sweat left behind by their quarry. The dog on arrival would then pick up the trail from the site of the located IED and track the person who laid it (Frankel, 2015)

In the US, law enforcement officers are regularly killed during high-risk tracks for armed subjects. These events provide a valuable contemporary example of how dangerous pursuing an armed and aggressive enemy can be. Both police and military forces often train by tracking a subject and then moving straight in to apprehend with a bite from the dog. When the subject is armed, this can often lead to the dog and handler being shot (Shettler, 2013). Having a dedicated tracking dog and handler that can read proximity alert (the body language cues a dog gives indicating the closeness to the subject during a track) is key to force protection during a high-risk track.

The focus on the southwest pacific region, which is a region of renewed strategic focus due to geopolitical shifts in the last decade, is an ideal operating environment for a tracking dog. Tracking dogs are invaluable in all operating environments, but even more so in close jungle terrain where the threat of ambush is high and difficult to counter. Having a cadre of tracking dog trainers in the Australian Army would also offer additional opportunities for collaboration with partner nations, with the private industry currently filling this role in the region.

MPDs/CADs compared to the Tracking Dog

Tracking dog selection, training, and ongoing readiness is relatively cheap and uncomplicated with adequately skilled trainers and handlers. Unlike MPDs or CADs, single purpose tracking dogs are typically able to enter work at a much younger age (as early as 12 months) and are typically cheaper to acquire due to the simpler nature of training required to produce a tracking dog.

Tracking dogs offer advantages in a more regulated environment as they are handled (and should be worked) entirely on lead. The risk of injury through failure to recall are therefore not present, nor do they require the use of training tools which are being progressively banned by various states and territories (such as the prong and e-collar). Compulsion based tracking techniques are not conducive to creating a dedicated and stubborn tracker.

Whilst MPD and CADs are trained in the art of tracking, the typical in-service German Shepherd or Belgian Malinois is unlikely to manage 15km+ tracks due to the traits that also make them incredible assets in apprehension. Ideally though, an MPD or CAD working in tandem with a tracking team is an incredible asset, as once the tracking dog has indicated the enemy is close the MPD/CAD can be used in area search to engage the threat if that is considered a tactically sound decision based on the level of threat.

Conclusion

A single purpose tracking dog capability would save lives on operations and provide more options for commanders to pursue an enemy. They can provide friendly forces with an early warning of a threat when in pursuit of withdrawing enemy forces, offering a tactical advantage that would otherwise be unavailable. A tracking dog can also track at a significantly faster rate than visual trackers. They are cheap to acquire and train. As shown resoundingly in Vietnam and Malaya – tracking dogs are a significant force multiplier on war-like operations and low-level conflicts.

This capability is one which some may consider unnecessary in the contemporary operating environment. However, there is currently nothing in existence that can replicate the ability of the tracking dog to isolate a single human odour, follow it for many kilometres, and provide early warning when approaching the threat. Standing up a dedicated tracking dog capability now will be significantly easier than in the middle of some future campaign, and it would establish greater corporate knowledge and experience within army.

Thought your story was brilliant.

I managed to procure my Current Belgian Malanoise after I enquired post discharge if any " unsuccessful " pups were to become available I would be interested.

My dog was deemed unsuccessful due to his lack of aggressive behaviour so I retrained him to track.

Something the ADF should consider perhaps??

Regards

Paul Thorp

33 years ADF.

We would be grateful for further comment from you in regards to this matter

were abandoned.

My second point is that I do firmly believe that future warfare will likely need the use of dogs; they are in effect a sensor that enables greater tactical decision making for a manoeuvre commander. I believe we should look to our history in Vietnam and the massive successes there. From Vietnam, Rhodesia, Malaya, Iraq, Afghanistan, and today US SOCOMD is training their MPCs to track longer and better with an awareness of proximity alerts. Given the fragility of tracks and time being a critical factor in tracking success, have few assets spread in an AO is not conducive to mission success.

I couldn't agree with you more. Having spent three years as an Instructor / Team Leader at JTW I pushed heavily to have canines introduced into the Visual Tracking Courses. I had success but only in the form of Law Enforcement canines.

I feel there is a swing toward being more technologically empowered. Nothing compares to the sensory inputs possessed by a canine. Their sense of smell is about 100, 000 more sensitive than a humans. No technological sensor can match it. While their sense of hearing can detect sound at ranges of up to four times greater than a human can hear.

I have a Labrador who I have managed to train to scent track. As an 18 month old puppy we sent three days tracking deer to end in a successful hunt. His sense of smell coupled with my visual tracking skills resulted in a good outcome.

My final thoughts, all Infantry Battalions should have a dedicated Combat Tracking Platoon, with each Tracking Team having a organic canine at their disposal.