A common line in all career interviews: “you define your own career success”. But is this true? Many of us have played the game and lost when trying to find army jobs we think are the right mix of fun while being both challenging and rewarding. Many more of us have failed to attain a desirable posting location, unit, or role we thought would be best for us. While we often look back and recognise that those unpredictable and sometimes ‘not want’ detours throughout our career were crucial in forming us into the officer or soldier we are today, there is still a requirement for the Army to provide its people with a direction or pathway that minimises both personal and professional disruption.

Career success

People want to feel like they have some impact on where their career takes them, not just to be a passenger. Therefore, Army should aim to offer a multitude of career paths that account for differences in strengths, weaknesses, personalities, and preferences. Whilst it is unreasonable to expect everyone to always get their posting of choice, the organisation should give its people the opportunity to select the path they take toward their definition of career success. Selecting a different path to the status quo should not define their competitiveness for future selective postings. We must break free of the thought that there is but one path to each milestone posting in a career.

Career models

Army has moved through many iterations of career models that aim to produce officers and soldiers with sufficient knowledge, skill, and experience to fill highly demanding roles later in their careers. Each time it seems to fall back to the tried and tested model that looks something like this: high performing officers and soldiers are placed in high stress postings that allow them to build credibility and a reputation for being capable of working long hours under arduous conditions. This then places them in good stead to compete for the next high stress role considered competitive and proves their worth when competing for future promotions. In summary, our very best spend their careers working jobs they don’t like to compete for other jobs they probably won’t like.

There must exist a fine balance between enabling people to choose their own career and giving people challenging positions which develop them. If everyone worked in the posting locality of choice they may not want to move when necessary, and if everyone was comfortable in their role they may not grow. Regardless, in a time where retention is a major problem, something must be done to meet the needs of Army’s people.

Let’s face it; career advisors have an extremely difficult job. They have to carefully balance filling current force vacancies with growing potential by giving critical experiences to a broad enough pool of individuals to meet future key appointment vacancies – and all the while accounting for attrition through discharges and service category transfers. Further, there is an increasing aspect of career management that demands planning for future force constructs, many of which are undefined. Thankfully, in recent history they have not had to do so simultaneous to Army executing high intensity warfare.

Career management of old

As a junior officer, I grew up in an era where the Directorate of Officer Career Management was trying exceptionally hard to implement a career model that allowed for individuals to choose which career path they took as a junior officer. Unfortunately, it was also widely understood (whether true or not) that if you chose anything other than the Command-Leadership-Management (CLM) pathway you were destined to go nowhere in your career. In an organisation that loosely defines career success as attaining promotion as quickly as possible, with continued promotion right through to the end of your career, it was not palatable for many of my peers to pursue career pathways other than CLM, regardless of what their strengths or interests were. Stepping off the CLM pathway was actively discouraged.

Progress so far

Thankfully the sands are shifting on this subject. Two things are happening: firstly, the ‘quiet quitting’ revolution is happening in broader industry whereby people are choosing to spend more time with their families doing things that they enjoy rather than working long hours for no additional pay or recognition. Secondly, people are moving jobs more frequently. Both are largely a by-product of the global pandemic and the subsequent re-assessment of priorities after the realisation of one’s own mortality. The translation for Army appears to be that people are less willing to accept positions or posting localities that they see as high tempo, unrewarding, and/or undesirable. As a result, they are more likely to accept desirable positions at the detriment of their career and are likely to discharge if this does not happen. In short, Army’s people are rapidly expanding their ‘quit criteria’ and Army is going to struggle to meet the needs of its people to stem the loss of human capital.

Possible solution

Army has recently introduced Human Resource and Capability Development pathways, although they again appear to be an option only for those who are not or do not wish to remain on the CLM pathway. It is a step in the right direction. But these pathways shouldn’t be an afterthought for people who are midway through their career. They should be made known for junior officers to aspire to follow. Doing so creates a level of self-sorting for Army whereby those who are interested in people, or projects, or operations can specialise in those fields as a captain and then serve 10 years performing at a very high level in their chosen field as a major and lieutenant colonel. Similarly, those who are interested in commanding and leading can do so. Each group will likely become much more proficient in their chosen field rather than spending only a few short years within their stream throughout their career.

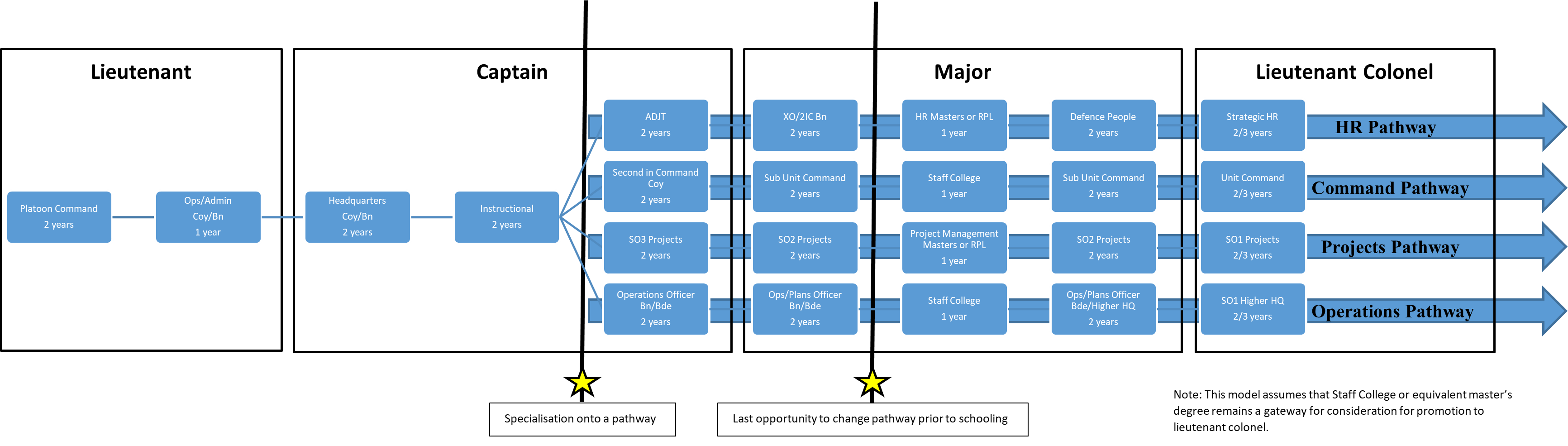

This solution involves reverting back to having multiple career pathways that all provide a viable pathway to lieutenant colonel and beyond. The premise is simple, an officer’s time as a lieutenant is used to provide them the foundation for all the possible paths available to them as a captain, major, and lieutenant colonel. There is no change to the extant lieutenant postings. The first four years of captain allows the officer to build on that foundation and begin to identify key strengths, weaknesses, and interests that will allow them to select a career pathway prior to their final posting in rank. The model places them in a company or battalion headquarters for the first two years in rank to ensure they understand how unit planning and administration works. After this, an instructional posting allows them to confirm their knowledge either within a corps school or ab initio training centre. They then choose a specialisation to progress onto a pathway: human resources, command, projects, or operations. Once on their chosen pathway they are mentored for the next rank and position and move through those positions which progressively increase in level of responsibility within their chosen field.

Of course, CLM remains the basic building block of being an Army officer but allowing people who desire that style of work to complete multiple postings in a CLM role leads to higher levels of engagement, higher performance, better leaders and managers, and happier, higher performing organisations. Employing those who are interested in project management to solely serve in project roles has the same effect, along with human resource people and operations and planning people. Tailoring a career path to an individual’s interests, needs, and strengths may give us the best Army officers we have ever had. Additionally, providing our officers broad battalion experience as a lieutenant ensures that they are grounded in the basics prior to specialisation. This is not dissimilar to how we handle trade specialisations and regimental positions within the soldier cohort, and largely how we already manage our lieutenants. We lose nothing, yet have a lot to gain.

The career advisor and assessing officers would provide individual feedback on where individuals may be best suited, but ultimately it should be the individual that makes the final decision on their pathway. The risk of the career advisor not being able to fill certain roles due to lack of interest in certain career pathways over time will become minimal. Providing career advisors treat all pathways as equal for both progression and promotion, what will be created is a demand market. A pathway that is less desirable would create a vacuum that would cause promotion ahead of time within that pathway and subsequently create demand for that pathway. Demand can also be manipulated and managed by the Directorate to fit emerging needs.

Once on their chosen pathway, the order of progression for certain roles has been adjusted. A sub-unit second-in-command immediately becomes a sub-unit commander following that posting, and an operations officer operates within battalion, brigade, and higher headquarters throughout their career. Officers are then given final opportunity to change specialisations prior to higher schooling which consists of either Command and Staff College or a master’s degree in their chosen field.

This assumes that a master’s degree broadly remains a gateway for promotion to lieutenant colonel. Beyond higher schooling the officer remains on that pathway until promotion to colonel. This trades breadth for depth in the officer pool which could be considered a key weakness; however, it generates sustainable tempo which could be scaled in the case of mobilisation. It ensures that all officers are being trained and mentored adequately to be able to promote to the next rank in a substantially quicker timeframe than is currently possible. In the unlikely event of mobilisation, anyone beyond fourth year captain can be rapidly progressed to the next rank or position with significantly reduced risk of officers not being prepared for the next position on their chosen pathway.

Due to the removal of sub-unit command and unit command as key ‘preferred gateways’ for progression, officers are now placed in their field of expertise for longer postings and time spent in their field takes up the majority of their career. Rather than having single gateways that everyone must pass through, each officer’s gateway is relevant to their career pathway. This means they are likely to be much better in each role they are placed in as each posting directly builds on the last. Commanders command for longer and become better commanders. Planners plan for longer and become better planners, and so forth.

Conclusion

In conclusion, career advisors should seek to post the right person to the right job at the right time. To make this easier, Army should create pathways which cater for the strengths, weaknesses, personalities, and preferences of its people in line with service needs. The creation of multiple pathways for officers allows our people to be more knowledgeable in their chosen field which in turn generates organisational competence and loyalty. It also has the potential to generate significant increases in engagement as people are employed in a role that they find interesting throughout the entire duration of their career. The subsequent ‘self-sorting’ effect means that the career advisor’s role becomes easier while simultaneously generating greater capability.

Response from CM-A:

This article re-engages with the debate about whether Army should grow 'generalists' or 'specialists'. We need our people to have an experience as broad as possible before assuming key command appointments. This allows them to generate ideas and solutions to problems from a broader foundation of knowledge and experience. CM-A welcomes new ideas and debate on career models and pathways as this enable the best outcomes for Army as it aims to retain talent and contribute to Army and Army People System initiatives.

I like Oscar Wilde’s advice about being self-aware and following our own interests with passion, “Be yourself - everyone else is taken.”