A note from The Cove Team: This article was published in Smart Soldier 54, November 18. You can access the full edition on the DPN in the Army Lessons Online page. (Tip: Search for Army Lessons and select the second search option).

The Battle of Fire Support Patrol Base Coral – Insights for the Modern Soldier

'Any military commander who is honest with himself….will admit that he has made mistakes in the application of military power…through mistakes, through errors of judgment.' Robert S. McNamara, The Fog of War, (Film)

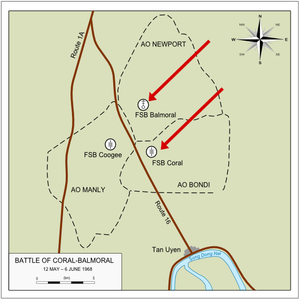

This year (2018) commemorates the 50th anniversary of the Battle for Fire Support Patrol Base (FSPB) Coral, which took place between 12 May and 06 June 1968. The Battle for FSPB Coral was a part of the largest operation undertaken by the 1st Australian Task Force (1 ATF) in Vietnam, yet it has remained largely forgotten in official literature and unknown to most Australians.

On 12 May 1968, 1 ATF deployed to obstruct the withdrawal of North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces following their bloody yet unsuccessful attack on Saigon. The first part of the deployment saw the 1st Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment (1 RAR), deploy to establish FSPB Coral in Area of Operations (AO) Surfers – and remain there, under heavy attack until their withdrawal on 06 June 1968.

Whilst most Australians have forgotten this battle, a smart soldier should not. The Battle for FSPB Coral should not only be remembered as a memorial for those who fought, but remembered for the lessons it can teach us – lessons learnt through review of the planning and execution of the battle; its mistakes and successes alike.

The Importance of Reconnaissance

Two days prior to the occupation of FSPB Coral, an aerial reconnaissance of the proposed landing zone (LZ) and battle position (BP) was conducted.

Two days prior to the occupation of FSPB Coral, an aerial reconnaissance of the proposed landing zone (LZ) and battle position (BP) was conducted.

However, due to the risk of small arms fire, this reconnaissance was limited to a single fly-over at 2,000 feet. As a result, commanders were unable to obtain an adequate appreciation of the ground which they were to occupy. In the absence of this, commanders had to rely on map reconnaissance supplemented by intelligence from the US 1st Division who were tasked with securing the LZ prior to the occupation of FSPB Coral. The lack of reconnaissance had compounding effects, as it, in addition to an error in map reading, resulted in the Regimental Reconnaissance Party incorrectly identifying that they were approximately 1km from their intended location when landing at the LZ on 12 May 1968.

This error in appreciation directly led to significant errors in the occupation of the FSPB Coral defensive positions and added unnecessary complexity to the already strained tactical situation. Yet, despite these errors, junior commanders worked with the information they had – marking established company and artillery positions on battalion maps and attempting to tie in the position as best as possible, regardless of the errors that led to their current dispositions.

Tip 1: Time spent on reconnaissance is seldom wasted. The information gained through reconnaissance can be the most valuable piece of information you receive about a mission or operation. A higher commander, detached from the tactical fight, will not have all the information necessary. The commander will use their staff to gather intelligence, prepare overlays and allocate resources – but unless they have either placed a foot or an eye on the objective, they will have incomplete information. Therefore it behooves the soldier on the ground to do so, and inform the plan.

Mutual Support

The defensive layout at FSPB Coral on the eve of 12 May 1968 was poor; this being the result of a confused occupation in the preceding hours. The confused occupation caused subsequent errors in the development of the position, particularly during the 'tying in' process of the various sub-units. The position at the end of the deployment has been described as 'actually two separate bases' with the two artillery batteries sighted 1500m apart and the New Zealand 161st Artillery Battery left isolated. Despite discrepancies in official records and first account reports, it is clear that the local defence commander did not tie in the overall defence plan and he and his team either forgot or ignored a key principal of defence – mutual support. With limited daylight remaining when the final elements of 1 RAR arrived on the ground, there was no opportunity to immediately rectify the situation – the position was secured as best as possible with the batteries tying in their individual machine guns and the 1 RAR Anti-Tank Platoon sighting its two recoilless rifles along the frontage of the Mortar Platoon. These were actions that were ultimately completed by subordinate commanders due to the lack of a defensive coordinating conference or orders by the FSPB Defence Commander.

Tip 2: 'Defence is the strongest form of warfighting.' So the former Prussian General, and most quoted military theorists of his time, Carl von Clausewitz, maintains. If done correctly it can provide significant benefits including affording the greatest security to your own forces against a numerically superior enemy. Yet without mutual support – the support, which units provide to each other because of their dispositions, capabilities and assigned tasks – the defence is merely a compilation of fragmented units which act independently. At all levels of command we must consider mutual support. Your ability to achieve the defensive mission is not in the achievement of the individual, it is in the ability of the team to support each other.

Combined Arms

The 1 ATF was Australia’s largest combined arms commitment to war since WW2, consisting of two infantry battalions, supported by two gun batteries, a squadron of armoured personnel carriers, a field engineering squadron and a flight of reconnaissance helicopters. Each infantry battalion was supported by other combat arms, which provided intimate and invaluable support; without which they would not have been able to survive against a numerically superior enemy with a home field advantage. The effect the artillery provided to the infantry during the initial attacks by the enemy at FSPB Coral was immeasurable. Without their support in defence, the infantry would not have been able to repel the continuous attacks by the enemy. Additionally, during a battalion attack where 'artillery and mortar fire provided a protective box around the infantry and armour allowing them to methodically destroy individual bunkers', 1 RAR used combined arms and demonstrated the effectiveness of using infantry intimately with armour, achieving a task that if conducted by infantry alone, would have produced a high number of casualties.

Tip 3: Combined arms warfare, is necessary in all forms of combat. Combined arms hits the enemy with two or more arms simultaneously in such a manner that the actions he must take to defend himself from one make him more vulnerable to another. To ignore the requirement for combined arms leaves the single combat arms unit at threat from forces it cannot defend against. It is not a new concept, and there are many historical examples from which we can draw from. In 1066 at the Battle of Hastings, a Norman army consisting of infantry, archers, and cavalry defeated the English, consisting of predominantly infantry. The Norman army used combined arms to outmatch the English, suppressing their infantry through the use of archers, making them vulnerable from direct engagement from the infantry and cavalry. Take an infantry section, tasked to clear an enemy recon outpost, which has dominant observation and fields of fire over its approaches. Whilst the infantry section 'technically' has the relevant combat ratio to achieve the task, it is vulnerable to direct fire and observation, and thus will always incur a higher degree of risk if conducting any offensive manoeuvre. A combined arms approach would see the section augmented with artillery support allowing it to suppress the enemy outpost and deny observation. This in turns allows the infantry section to rapidly and safely advance until it is within range to engage and neutralise the enemy with its own weapons. Similarly, augment the same section with armour that uses its speed, firepower, protection and ability to deliver shock to assist in suppressing the outpost whilst protecting the infantry during the advance – another textbook example of combined arms.

Communications

The standard of artillery communications has been used as the benchmark for measuring radio communications effectiveness across the Australian Army for many years. The radio communications at the Battle for FSPB Coral was no exception. In fact, from many records it can be argued that it was the effectiveness of these communications, the speed, detail and accuracy of reporting, and the overall calmness of the operators, that enabled the command and control of the battle. Communications was a pivotal key to the effectiveness of units at FSPB Coral. In an environment where it was necessary to co-ordinate ground defences (and limited assaults), control artillery and aerial support as well as co-ordinate resupply and aeromedical evacuation (whilst under assault from a numerically superior enemy and with communication lines cut), the standard of communications from within FSPB Coral can be measured as exceptional. A testament to this is recorded in the 1 RAR Duty Officers Log from FSPB Coral which is held at the Australian War Memorial.

Tip 4: 'No plan survives H-hour'. A famous quote, indeed – it has been uttered by thousands and experienced by many. However, when a plan requires modification ‘on the fly’, robust communications is the key. Regardless of the size of the team, there is an inherent need to ensure that not only are communications established, but they are manned by competent operators who can provide accurate, clear, concise and relevant information. Smart soldiers should be proficient in primary and alternate communications, understand how to problem solve when communications are lost and be comfortable working in environments where communications are degraded. During the Battle for FSPB Coral some communications were disrupted by enemy mortar and RPG fire destroying the lines. The Battery CP operators and Section Commanders understood the alternate communications plan and reacted by using the battery net for command communications as well as verbal and hand signals to relay the fire plans to the guns. With the improvement of our communications equipment there is a tendency to forget the basics such as hand signals, yet they play a more important part at the small team level than is often understood.

Resilient Soldiers and Teams

Soldiers and small teams are the most important part of our organisation. Whilst there are many factors, which may contribute to their success on the battlefield, ultimately it is, ‘the capacity of individuals, teams and organisations to adapt, recover and thrive in situations of risk, challenge, danger, complexity and adversity’ that will often be the defining feature in the overall success or failure of the mission. Faced with a numerically superior enemy, with home field advantage, and a dispersed defensive position that lacked the application of key defensive principles – the soldiers and teams at FSPB Coral demonstrated numerous examples of superb individual and organisational resilience.

During the initial enemy assault the artillery battery, having never fired Splintex ammunition prior to the battle, and therefore not knowing the correlation between time fuse setting and range, were required to employ it against the enemy attack at close quarters. Following two rounds of adjustment (which by accident neutralised enemy depth/ reserve positions), the battery was able to use the Splintex ammunition with devastating accuracy and confidence for the remainder of the battle. Additionally, when elements of the infantry in forward positions were forced to withdraw, they displayed utmost resilience: to follow orders and withdraw to their secondary positions, to regroup and prepare for the counter attack against an enemy with momentum and superior numbers. Their ability to retake their positions under the most stressful and challenging circumstances was due to their training, their discipline and ultimately their resilience.

Tip 5: The resilience of a soldier and the team is just as important during training as it is on operations. It is every commander’s responsibility to build soldier resilience and create individuals and teams that, like those at FSPB Coral, thrive and prevail where others may not. Whilst it is important to develop soldiers that have a greater capacity for the directed task, it is more important to make them understand the task so that they can be resilient through the principle of ‘adapt, recover and thrive’. Individuals and teams placed in diverse and difficult situations, faced with challenges and opportunities alike, will store these experiences and draw from them when needed, building the capacity for resilience – as was demonstrated by the well trained, disciplined and resilient soldiers and teams at FSPB Coral.

'The only real mistake is the one from which we learn nothing.' John Powell

It is human nature to make mistakes, and as smart soldiers, we must learn from these mistakes. Yet, despite the mistakes brought about by the complexities of the Battle for FSPB Coral, there were also a number of successes. It can be argued that ordinarily, teams (organisations) don’t learn from success. Whilst individuals use experiences gained to shape future behaviour, the team can often fail if these successes, like mistakes, are not analysed. When teams fail to analyse why successes have occurred, they fail to expand their knowledge about the situation or alter their assumption about how an action occurs. Therefore, it befits a smart soldier to review mistakes and successes alike.

Regards Steve.

email above and 0431481634 is operational, anytime. regards Buzz.

I'm the younger brother of Tom Strange who served in the mortars with you during the battle. He's passed now and never talked about it, but I would appreciate it if you could fill me in on his part so I can try to understand his latter years better.

Best Regards

Ken Strange

impken@yahoo.com