This article was written by CAPT Catherine Stevens and published in Smart Soldier 59, Feb 20. You can access the full edition on the DPN in the Army Online Lessons page. Tip: Search for Army Lessons.

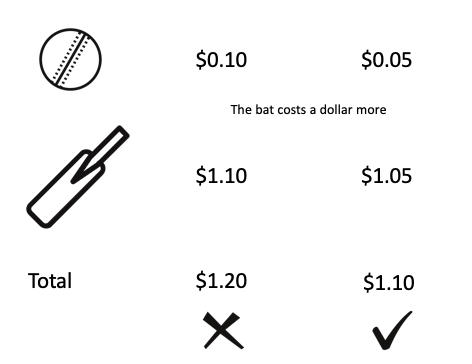

If a bat and a ball together cost $1.10 and the bat costs a dollar more than the ball, how much does the ball cost?

What can this simple maths problem tell us about our thinking? A lot more than you may realise.

While the question may remind us of how much we disliked maths throughout school, our answer and the mental processes we use provide great insight into how the human mind operates. So much so, that for the past 15 years, researchers have posed this and similar problems to study human responses.

Was your answer 10c? Research shows this as the most common response if it’s the first time you’ve seen the question. If so, congratulations, you’re just like most of us! However, you also made a mistake. Let’s see why:

An explanation as to why we fall prey to this mistake lies in our mind’s thinking systems that we use while awake.

When we see the question, it looks simple – something a young child could answer – and because of this, we rely on the first instinctive answer we can automatically generate. It’s just that in this case, it’s wrong.

Psychologists, in examining this instinctive and automatic thinking, have come to believe our mind has two systems that both guide our thinking and decisions.

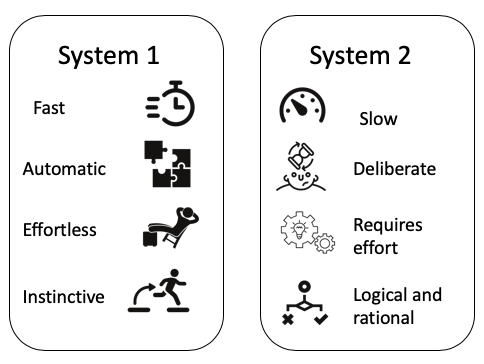

System 1 and system 2 – the fast reporter and the slow editor

System 1 is known as fast thinking. This system is automatic and we use it without us even knowing or controlling it. It is instinctive, requires little energy or effort and helps us to process the large amount of information we encounter every day. To do this, system 1 relies on a number of mental short- cuts and biases, which can leave it prone to making systematic errors in judgement.

On the other hand, system 2 is our slow thinking. It is rational, logical and deliberate, so we tend to engage it only when we think it’s required. We’re in control when we use it, but it takes a lot of mental energy to do so.

These systems together can be thought of like a group of news reporters and an editor.

The news reporters are our system 1, and they constantly generate stories and ideas that are sent to the editor, our system 2. While we would hope the editor diligently checks each story for accuracy before publishing, our system 2 is both lazy and overly trusting. As it takes so much mental energy to properly engage system 2, the editor, unless we tell it otherwise, prefers to just agree with whatever system 1 suggests, which is not always optimal, and can have potentially disastrous consequences.

This is exactly what happens in our minds when most of us claim the ball costs 10c. This was our automatic response from system 1 and, because the question appears easy, our system 2 decides this answer can be trusted and endorses it, rather than investigating further. This is how our mind is tricked by a well- intentioned system 1 thought.

To understand how these systems work a little deeper, here are the top four things you need to know:

- Most of our time is spent in system 1.

Although we like to think of ourselves as logical, rational beings who are in control of our thinking, the reality is that, most of the time, we rely heavily on system 1. Our system 2 runs in a low-effort mode in the background, and we tend to call upon it only when needed.

- Our mind is energy efficient.

If there’s a mental path of least resistance, you can guarantee our mind will take it. We operate in and prefer system 1 because it uses significantly less mental effort. Using system 2 is hard work and there is little point if we don’t think that the energy investment is worth it.

- System 1 likes mental short-cuts.

Don’t be fooled! Whilst it led us astray with the bat and ball problem, system 1 can and does produce accurate thoughts and ideas. However, it also likes mental short-cuts and will often use these to fill any gaps it has when generating thoughts. Again, not all short-cuts are negative, but they can create thinking traps such as stereotypes and cognitive biases.

- Both systems are important – one is not better than the other.

It’s easy to think that system 2 is superior as it is logical, rational and deliberate. But the reality is that we couldn’t function in the world without both of them. System 1 enables us to react instinctively and automatically when required, and it helps us process the large amount of information we encounter daily. The option to engage system 2 provides us with the ability to solve complex problems that an uncertain world throws at us. The human race simply would not survive without both.

Becoming a better thinker

The evolution of the human mind to consist of these two systems allows us to be the humans we are today. So how do we use these systems to become better thinkers?

There’s no easy answer to that question. As they’re both vital, it’s not as simple as prioritising one system over the other.

However, awareness of our thinking and of these systems is crucial. It is unlikely that we will ever stop relying on system 1 for most of our daily actions, but becoming more aware of it, and its potential thinking traps, will help us identify times where we need to engage system 2.

The AEC Critical Thinking Portal is designed to be an introduction for ADF personnel who have heard of or are interested in critical thinking but are unsure where to begin.

The content will be reviewed and modified over time to improve its effectiveness.

The ADELE link for the Critical Thinking Portal is https://www.adele.edu.au/course/view.php?id=6382.

AEC is continually looking for ways to build and develop the course further. Please provide your suggestions to AEC via armyeducationcentre.ops@defence.gov.au.

Contact your local Army Education Centre detachment for more information on anything covered in this article.

Would you like to know more?

The Army Education Centre (AEC) is a great resource for all things learning and instructing and has information on critical thinking available Australia-wide. This includes a face-to-face Thinking about Thinking workshop as well as our Critical Thinking Portal available via ADELE (U).

More detail on the Thinking about Thinking workshop is provided in the poster below.

.