A useful collection of useful resources has been collated for the professional development of instructors. Check them out here.

“So, Miss, if the Vikings had the technology to navigate, how long would it take them to cover the circumference of the globe in their boats?”

It was at this moment as a high school teacher that I realised extending students who needed an intellectual challenge was going to be harder than I thought. I had often thought of myself as being an educator who thrived on helping students at the lower end of the academic scale. The opportunity to take a gifted and talented Year 7 history class early in my career highlighted that students who perform well academically also need their own type of assistance – thinking routines and questions that keep them challenged.

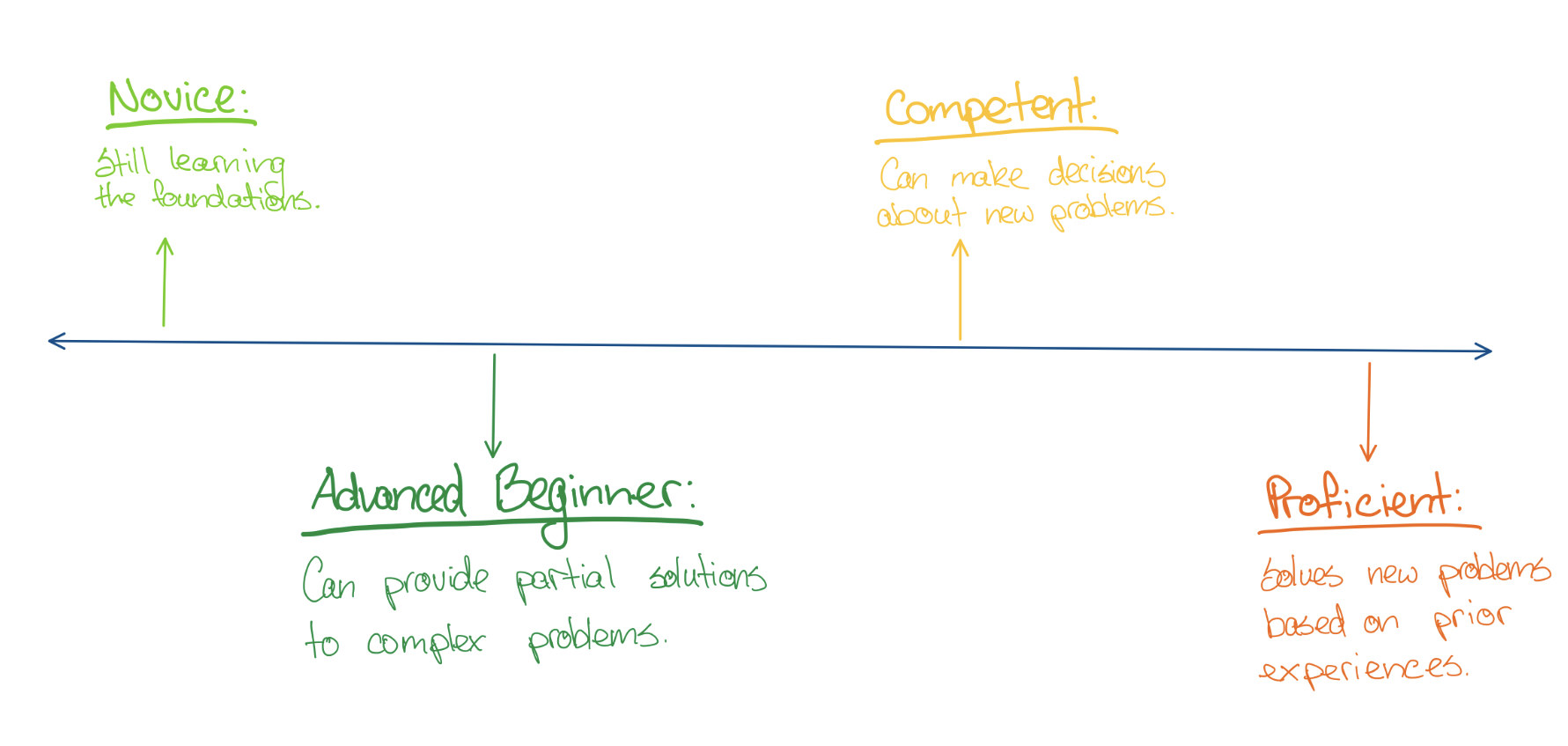

Instructing in Army is similar in many ways to teaching, particularly in terms of the diverse group of learners that both teachers and Army instructors can expect to see in their respective learning communities. Recently I facilitated a workshop on the novice to proficient continuum and its relation to Army training on a military instructor course. It was during this workshop that a Sergeant identified that in Army, we struggle to extend people at the top end of that continuum. In particular, he identified that because brigade learning environments include such diverse groups of learners, instructors tend to “cater for the lowest common denominator.” The result of this mantra is that our experienced members can become disengaged.

Instruction, like teaching, is a balancing act between making sure everyone understands the concepts being communicated while also trying to ensure that those who fully understand don’t switch off. In aid of this balancing act, I’ve identified two thinking routines to add to your instructor toolbox that ensure members across the continuum remain engaged during your lessons.

THINK, PAIR, SHARE

Think, Pair, Share: Before you get started

The think, pair, share thinking routine is drawn from the Military Instructor Course and the Project Zero Thinking Routine Toolbox (2016).

What’s the end state?

- Everyone has a chance to think about their answers before they speak.

- If you were to ask the whole group of learners a question directly like, “What are the benefits of this incoming vehicle fleet?”, you might get one or two answers. If you allow the group to think individually about the question first, you’ll get a different answer from everyone.

Try using this routine with:

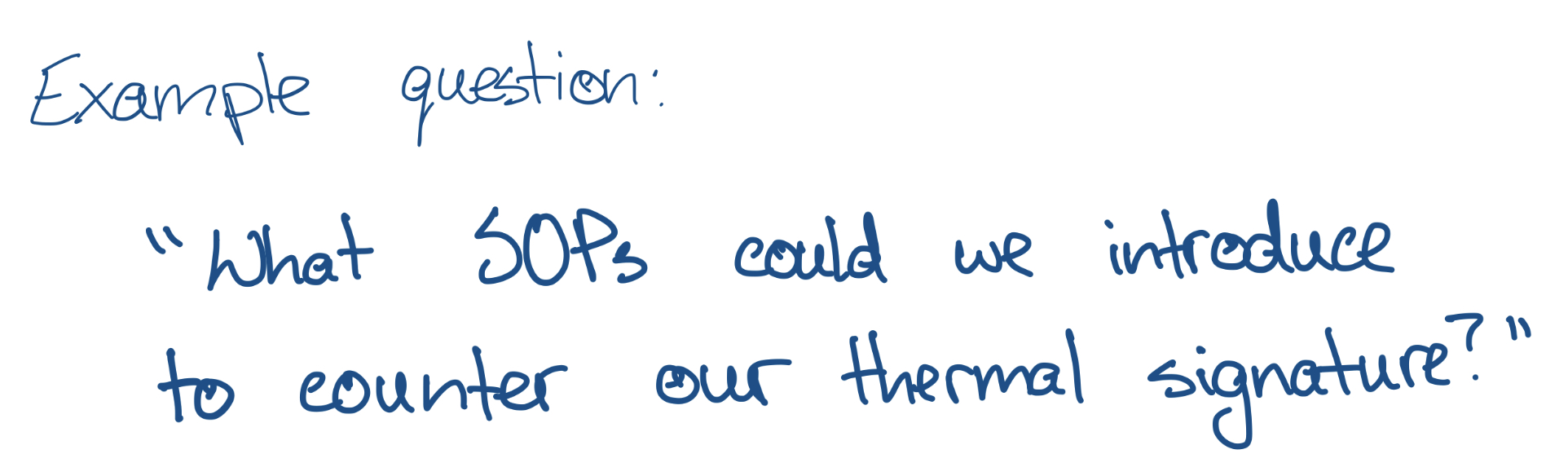

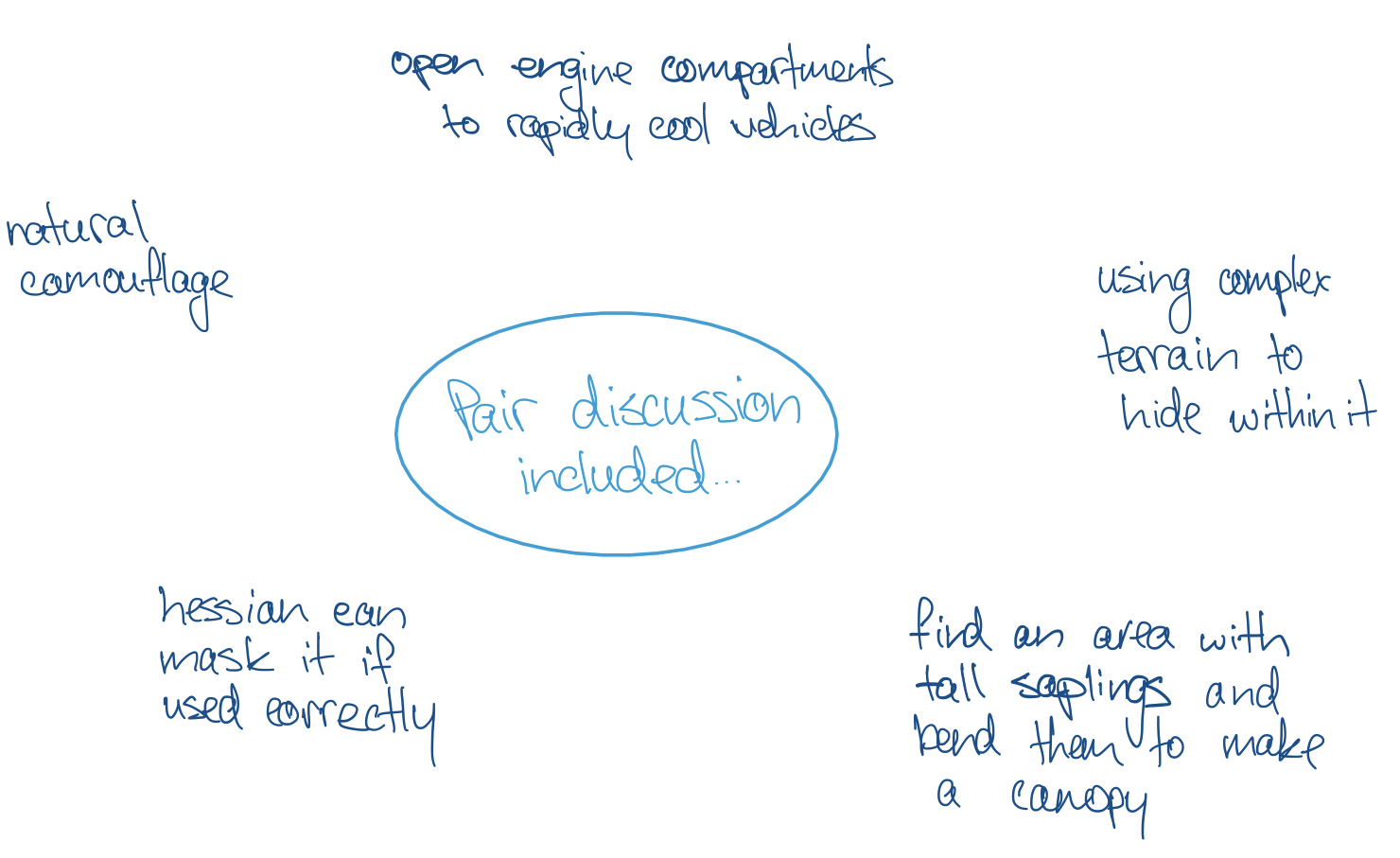

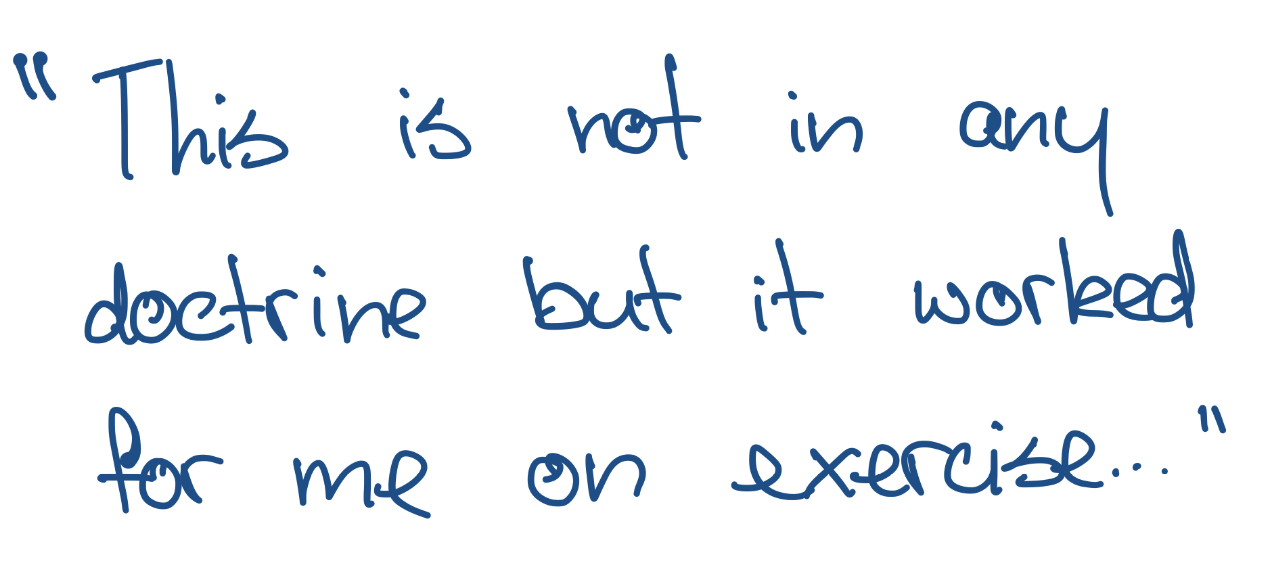

- Questions and concepts that are open ended. If there’s room for multiple answers or interpretations, there’s no cap on what competent and proficient learners can be thinking about.

- Lessons where you know incidental peer learning would be handy to include. For example, if you’re teaching a lesson about equipment that you know half of the group have had a lot of experience using but half have not, allowing them to think first then discuss their ideas ensures a transfer of experience to the novice learners.

- Works well at the end of a teaching stage to consolidate learning, and at the beginning of a lesson to gauge and validate the prior knowledge of the group.

Tips:

- Using a timer is crucial. If you can set a timer on your phone, it will ensure you allow enough time for the quiet “think” component of the ‘think, pair, share’ thinking routine but not so much time for the “pair” component that the discussion moves off topic.

- Write the question on a board where possible to make sure learners can keep coming back to it as an anchor for their thinking.

Think, Pair, Share: Routine procedure

- Ask learners to open to a new page in their notebooks. Present the question, then set a timer between 2-5 minutes in which they should write what they think about that question.

- Now get learners to pair up with someone. Learners have two minutes to present what they think about the question to their partner (one minute each).

- Bring the group back together and ask the pairs to offer what they were discussing. You might want to draw out any major differences, similarities or consensuses being reached by the pairs at this point.

THE 3 WHYS

The 3 Whys: Before you get started

This routine is drawn from the Project Zero Thinking Routine Toolbox (2016).

What’s the end state?

- Learners are able to scale their learning and understand what the concepts mean for them as well as the bigger picture.

- Assists the instructor in making connections between what is being learned and the real-world implications of the concept.

Try using this routine with:

- Your conclusion, to draw out the, “So what? What does this all mean for our job? Why is this even important?”

Tips:

- Leave some time for discussion after this one. You might find that your competent and proficient learners go on a bit of a tangent or spark ideas in the other learners. Remember that this discussion can provide productive incidental learning, so plan to have couple of minutes up your sleeve for it.

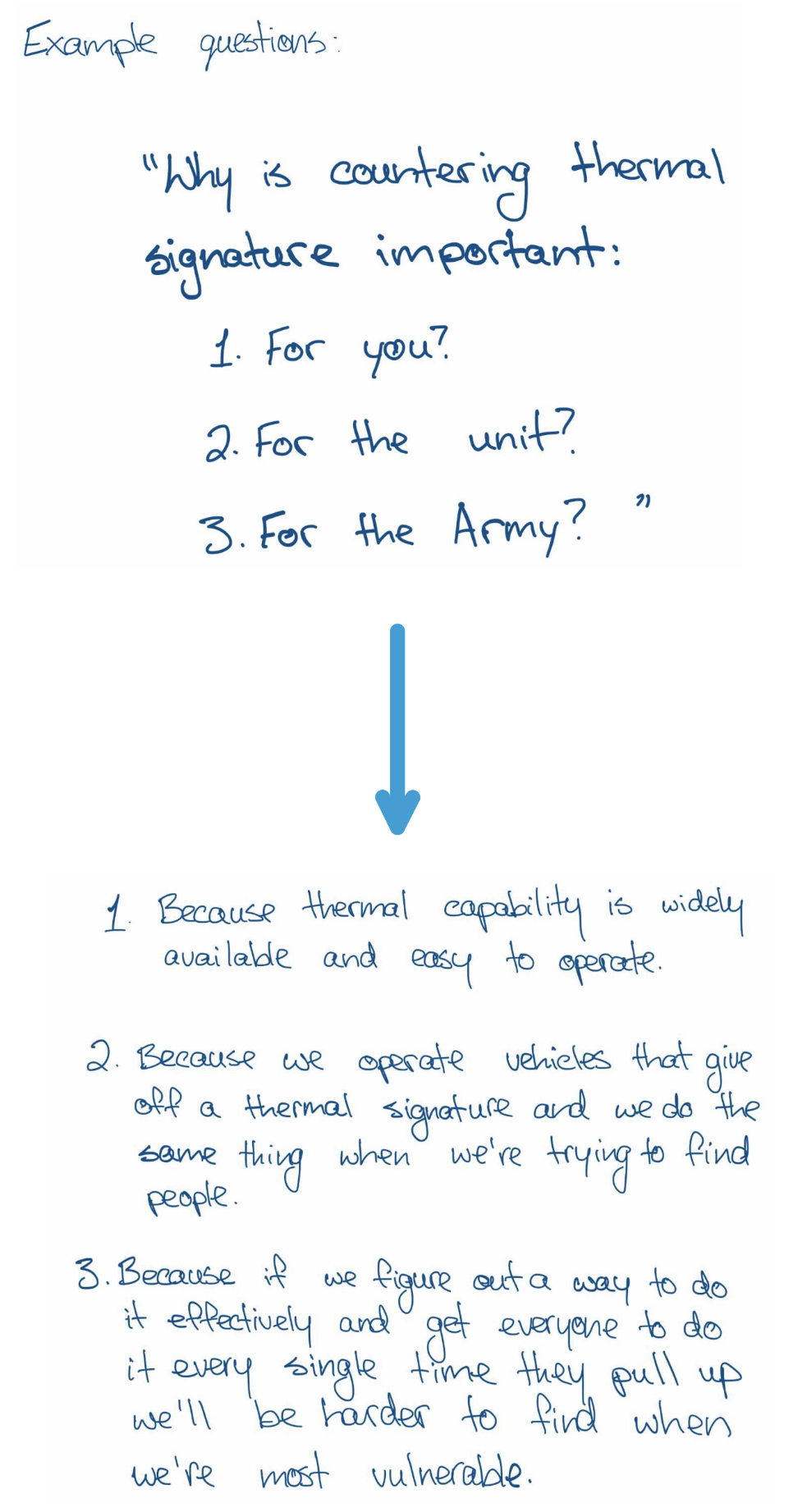

The 3 Whys: Routine procedure

With reference to the content being taught, ask learners to write down their answer to three questions:

- Why is this important for me?

- Why is this important for the unit?

- Why is this important for the Australian Army?

NOTE: Change the scale as needed. For example, it might be more relevant to think about why the concept is important for the individual, then their section, and finally the platoon.

Conclusion

Challenging learners at all stages of development is important. Challenging experienced learners in the workplace is crucial for the continual development of those members. Catering for diverse learner groups is challenging, so stow these routines in your instructor toolbox to ensure you keep the more competent and proficient end of your group engaged.

Have you been able to try either of these thinking routines in the workplace? Drop a comment below or get in contact to let me know how it went!