“…the fundamental mission of the Australian Army endures; to win the land battle… Our ability to adapt to changing circumstances more quickly than our enemies is a key factor in continuing operational success.”

– ‘Land Warfare Doctrine 1: The Fundamentals of Land Power’, 2014

Adaptability has been acknowledged as a key factor in winning the land battle. On the individual level, adaptability is about assessing the situation you constantly find yourself in, changing direction when that situation requires, and being prepared to make any number of changes to your operation as fleeting opportunities for success emerge. Being an adaptive operator requires a high level of analytical and creative thinking; developing such critical thinking skills requires hard work and practice.

Fortunately for the Australian Army, we are the beneficiaries of a national education system that encourages critical thinking in students from kindergarten all the way through to senior school. Most school leavers in Australia are naturally able to adapt to change, think critically in an unexpected situation, and wrestle through to a relatively successful outcome in the day-to-day running of their lives. For the most part, students in this country have been practicing critical thinking from a very young age at school, perhaps without even realising. In the army, of course, the stakes are higher, as we expect our soldiers and officers to make the right decision in the high-stakes environment of conflict.

Where does training transformation come in to all this? While the Australian education sector has been emphasising a culture of critical thinking amongst students at all ages and stages for some time, the intellectual investment by the army has waned for a number of reasons in previous years. Although the role of the army will always be to win the land battle, winning the fight relies on having individuals who train hard in order to fight hard.

In 2022, all of army has been encouraged to ensure that training hard is a mental effort as well as a physical one. In order to continue to be a competitive fighting force, individuals must maintain an intellectual edge over our adversaries. The current training transformation aims to support this idea and encourage both individuals and collective groups within the organisation to take hold of their critical thinking practise. While it might seem like education has nothing to do with winning the land battle, it has everything to do with our success in the long run.

The development of the intellectual edge starts by supporting a culture of thinking, and encouraging soldiers and officers to think critically starts with our everyday training at the section and platoon level.

Below are two thinking routines to add to your instructor toolbox in aid of this challenge. The following routines are particularly well-suited for generating discussion among learner groups as they encounter new concepts and equipment for the first time.

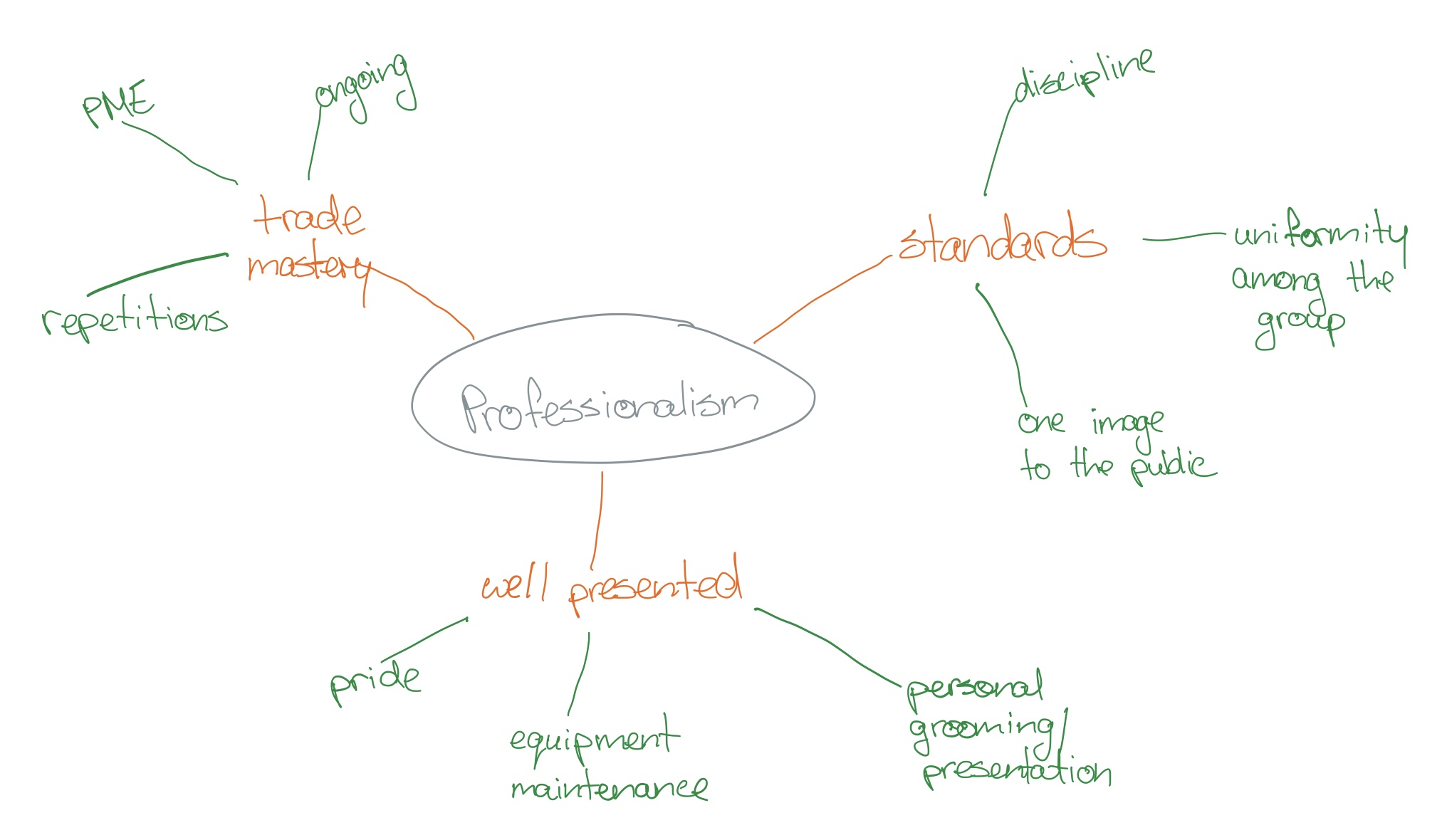

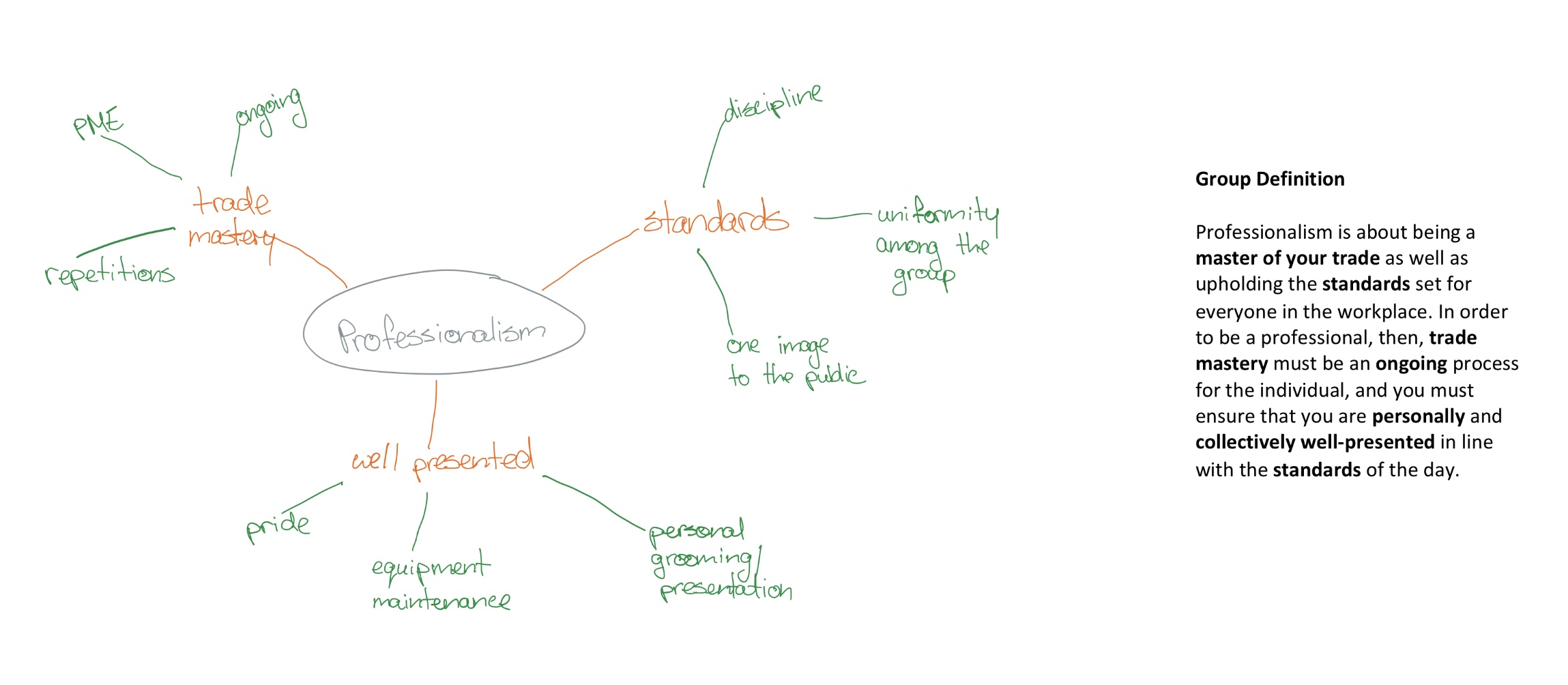

Make meaning: before you get started

The make-meaning thinking routine in drawn from Ron Ritchhart’s book, Creating Cultures of Thinking (2015).

What’s the end state?

- Learners devise a collective definition of a partially understood or new term, specific to their context. For example, when a directive for wider army is distributed, the terms used may be deliberately ambiguous to suit a whole range of groups working within the organisation. Terms like “training transformation”, “intellectual edge” or the army values can all be broken down more specifically in each members’ job role context.

Try using this routine with:

- Concepts or phrases that will generate positive discussion in the learning environment. For example, candidates on a Subject One Corporal course could benefit from defining the concept of leadership specific to themselves and the army environment.

- Concepts that have a different meaning in different contexts. You might consider terms that differ between the military and civilian environments.

- Ambiguous concepts, including those within directives distributed to wider army.

Tips:

- Use a whiteboard or some other large chart that can be viewed by the whole group.

- Use a different colour for each stage where possible.

- Best suited for groups between 5-30 members.

Make meaning: routine procedure

- Collectively provide 3-5 responses to the chosen concept with a single word or short phrase. An example of a small group make-meaning discussion is provided below.

- Collectively add on to responses contributed in the first round, to elaborate in some way to the meaning already forming.

- Based on the phrases and words collectively written on the board, each individual should now write their own definition of the original concept using the words contributed to the make-meaning discussion.

- Discuss individual definitions to work towards a collective agreement of the concept.

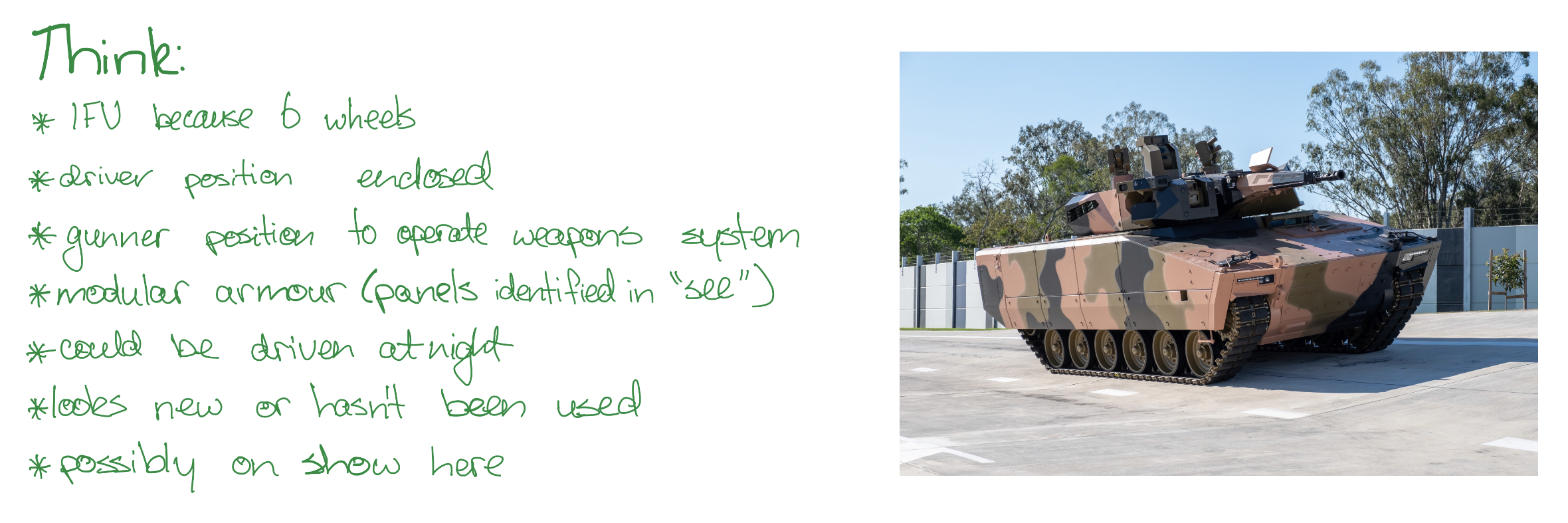

See-think-wonder: before you get started

The see-think-wonder routine is drawn from the Harvard Graduate School of Education Project Zero Thinking Routine Toolbox (2016).

What’s the endstate?

- Learners are encouraged to make careful observations and thoughtful interpretations of what they see.

Try using this routine with:

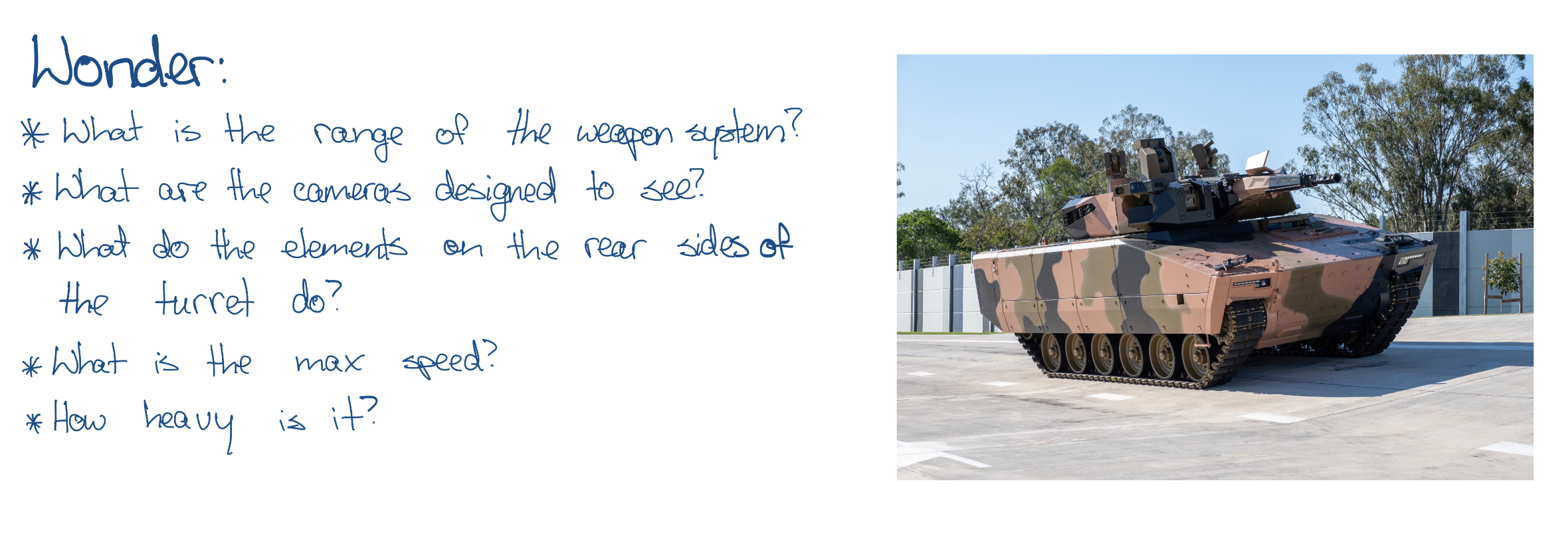

- New equipment, such as the incoming infantry fighting vehicle.

- Comparisons with old equipment. For example, a health platoon might look at the equipment used in the field hospitals of WWI in order to consider the advances in equipment over time.

- Comparisons with equipment used by other militaries.

- This routine could also be used to generate discussion around changing current affairs when appropriate media images are selected for consideration. For example, you might consider an image taken from the 2021 Kabul Airlift in order to generate discussion amongst the learner group about the closing of the war in Afghanistan.

Tips:

- Best suited when a projector screen or television can be used to display the image.

- Set a timer to ensure you don’t rush learner thinking.

- Suited for groups and sizes, provided the image can be viewed clearly by all learners.

See-think-wonder: routine procedure

- Learners prepare three columns or pages in their notebooks with the headings “see”, “think” and “wonder”. Brief the learners that they will be working independently for this section of the routine and should write as much as they possibly can in the given time limit for each section of the routine.

- Instructor displays the image. For this example, the small learner group used an image of the Lynx (Rheinmetall Armoured Fighting Vehicle).

- Learners have two minutes to write as much as they possibly can in their “see” column. Learners should only write what they can explicitly see.

- Learners have two minutes to write as much as they possibly can in their “think” column. Learners should now write what they think is inferred by what they see.

- Learners have two minutes to write as much as they possibly can in the “wonder” column. In this column, learners should write questions that they have about what they are seeing.

- Engage in a group discussion about what learners wrote at each stage of the see-think-wonder.

For further thinking routines you can head to the AEC – Military Instructor Course Toolbox on ADELE (accessible to current serving members) and have a look at the Project Zero Thinking Routine page, or have a chat to your local Education Officer.

If you’re able to try either of these thinking routines in your own workplace, be sure to drop a comment below with some feedback!