Part 1 was published in 2020, read it here: Tactical Spurs Part 1: Making Plans to Fight Battles.

Introduction: Risk is part of war, and this never changes

Soldiers often say that war never changes. We shrug our shoulders, talking of ‘Murphy’s Law’, ‘hurry up and wait’, ‘on the bus, off the bus’, and ‘days of boredom followed by moments of intense excitement’. All of these phrases suggest that, deep down, there are a number of things that are enduring in war … things that will endure for as long as humans decide that they have to go and do violence against other humans on behalf of their state.

The fact that war is risky is one of these things. Indeed, risk is probably one of the most defining factors in the nature of war. From daily work in an armoured vehicle park, through to conducting a contested amphibious beach landing, everything we do is inherently risky. Arguably it is one of the reasons we exist: to take risks on behalf of the Australian people to protect them from harm. Risk is our constant companion, a brother-or-sister-in-arms who always sits on our shoulder or trails behind us … sometimes helping us, but at other times just waiting for the moment to dismember an arm or a leg. Everywhere we turn, there is risk.

For military commanders at all levels this is a critical fact. Our role, most of the time, is to think about problems and make decisions. Considerations of risk – how much to take, when to take it, and who to put at risk – become absolutely central to these decisions. In many ways each choice is a trade with the devil on our shoulder, with risk as the currency. What makes it tricky is that often we are trading blind, pitching into an uncertain future against a cunning enemy. This means that the way we think and talk about risk is at the heart of our success or failure.

Our current way of thinking about risk

There is a fallacy that the Army doesn’t think about risk in a sophisticated manner. Actually, this couldn’t be further from the truth. The Australian Army’s model of Military Risk Management (MRM) is both simple and sophisticated, and gives us all the tools we need to make solid, risk-based decisions.[1]

It starts with a definition. Army defines risk as the ‘effect of uncertainty on achieving objectives or the end state’, which sounds complex but really isn’t. In war, we are almost always trying to achieve objectives based on an uncertain and chaotic situation that we can’t predict. ‘Risk’ is the potential impact of that uncertainty and chaos on our plans, if things don’t go our way. If uncertainty and chaos bite against us, then bad things happen, and limbs tend to get ripped off. Not good.

The next part of Army’s model seeks to work out how much uncertainty there is, and how bad the bad things might be. This is done by looking at the ‘likelihood’ and ‘consequence’ of a given risk. The first one seeks to tell us how likely it is that bad things will happen, ranging on a scale from ‘rare’ to ‘almost certain’. The second defines how bad things can get, starting at ‘minor’ and going all the way up to ‘catastrophic’. Add them together, and you have a scale of badness – a defined risk. An almost certain, catastrophic risk is one we are going to want to avoid. But we might happily accept a low, minor risk. The tricky ground is when we’re playing in ‘low likelihood’ but ‘high consequence’, and vice versa. This is where decision-makers earn their money.

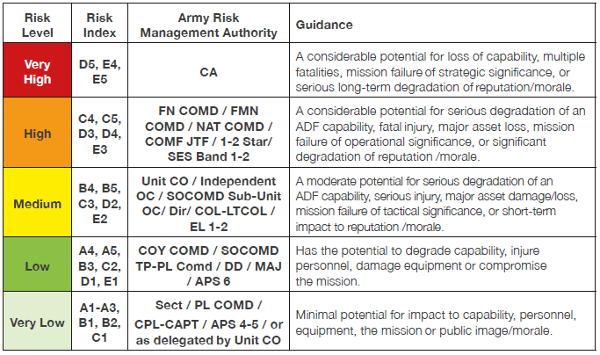

Once we understand a risk, the final and exceptionally important part is to answer the question, ‘who owns it, and what can they do with it?’ Again, Army helps us here. MRM is very specific about who can own what risk, and who can’t: outlining this in a clear-cut table that we can keep in a notebook (see Figure 1). As a CO and Battle Group Commander, I can accept a ‘MEDIUM’ level of risk, defined as ‘a moderate potential for serious degradation of an ADF capability, serious injury, major asset damage/loss, mission failure of operational significant, or short-term impact to reputation/morale’. This is exceptionally clear to me. If a risk is inside this level, then I can own it: fully, completely, and without reference to anyone else.

However, if a risk exceeds this ownership threshold (or my comfort levels), then I need to do something about it. This is where I’m a little old-fashioned. I continue to rely on what is called the ‘Four Tees’: treat, terminate, tolerate, and transfer. I can ‘treat’ risk, reducing its severity through applying more resources or changing courses of action. I can ‘terminate’ it, most likely by not doing the thing we are planning. I can ‘tolerate’ it (although I obviously can’t do this for a risk above my threshold). Or, most importantly, I can ‘transfer’ it to a higher risk authority. When I brief a higher commander on risk, this is the bit he or she needs to hear about: the risk I am transferring up.

Figure 1: Delegated Risk Management Authorities

Simple but sophisticated, with everything one would need to understand and take risks. So, despite this solid methodology, why does there continue to be a deeply ingrained perception that the Army is risk averse, or bad at risk? For me, this is because of two problems with our approach.

Two problems in our approach to risk

The first problem is that we are not very good at teaching or using our methodology. Risk theory is often seen as a tedious crutch, rather than a critical tool in unlocking mission command and tactical tempo. Importantly, a lack of constant reinforcement and practise leads to an uncertain lexicon within Army: each person thinks about risk differently, and more importantly defines it differently. We throw the phrase ‘risky’ around a lot, without a common conception of how much risk there is and who owns it. We also critically under-analyse and under-use the risk ownership we are all allocated by Army. This is our permitted manoeuvre space: a place we can operate without reference to other risk holders.

The over-bureaucratisation of risk is a key output of this lack of practise. Traditionally the first experience a young officer or NCO has with ‘risk’ is a highly complex RAS+ excel spreadsheet attached to an activity. With limited formal instruction in risk theory, and with the empty spreadsheet screaming at them to be filled out, our junior leaders understandably default to a ‘box ticking’ approach. This sets a ‘box ticking’ culture from the outset. Spreadsheets and forms also hate gaps, which drives our leaders to hunt and add risks that are already covered in standing policy, that are low enough to be within approved tolerances, or that simply don’t really exist. This approach, which thankfully is changing, over-complicates risk management.

The second problem is that we take a predominately defensive approach to risk, principally shaped by our in-barracks and training environment. It is absolutely right that Army applies a Workplace Health and Safety (WHS) mindset when working in barracks and when training. We operate highly dangerous workspaces and conduct dangerous exercises. Our responsibility to protect and safeguard our highly trained workforce is paramount. To do any less than this would breach our contracts with our soldiers and with Australia.

However, there are second and third order cultural outcomes that come with this. The foundational principle of WHS is that risk is bad, and therefore we should constantly seek to reduce it. All good in-barracks and when designing training. But in combat, this doesn’t work. There are times where we have to choose to take the most exceptional risks if it gives us the right tactical benefit. Often, given the chaotic nature of war, this is an exceptionally uncertain decision to make; but make it we must. As manoeuvrists we tend to admire ‘boldness’ as a character trait in our commanders: often this has to be synonymous with taking risk, even actively pursuing it. In war, risk is sometimes a good thing, even the best thing… as long as we can leverage it against our adversaries, and we aren’t accepting it unconsciously or as a blind or reckless choice. An inherently defensive culture towards risk in such situations can be fatal. At a minimum, it can stifle mission command and creativity: two key facets in unlocking tactical success.

What do we do about it?

We need to change our relationship with risk if we are to be adaptive, and truly unlock the benefits of mission command. This process has already started for Army, in terms of policy and procedure at least. As of late 2020, for example, the RAS+ is no more. Standing risks in training that are already recorded in doctrine or SOPs no longer need to be specifically recorded – as long as you are operating within them and adhering to them. The phrase ‘As Low as Reasonably Practicable’ (ALARP) has been replaced with ‘So Far as Reasonably Practicable’ (SFARP), reinforcing that ‘lowness’ may not be the ideal aiming point for risk. Both good moves, with the latter perhaps too subtle to make a broad difference.

For me; however, the real solution is more cultural than bureaucratic. We need to grab the risk devil on our shoulder and make friends with him. This starts with getting to know him better. Risk must become one of the defining topics in all tactical discussions, from the outset to the conclusion. Setting the tone of this is the commander’s responsibility, framed through our risk theory. During ‘scoping and framing’ of any problem, the commander should make articulating his or her risk appetite a central activity. This should be explicit; expressed in terms of, “I seek to take ‘MEDIUM’ risk of exposing reconnaissance forces early to confirm crossing sites”, or, “I am not willing to accept a ‘HIGH’ risk COA that splits the BG on three axes”. Risk then becomes the key currency of planning and execution – with commanders at all levels discussing and trading risk to help maximise tempo and mission command.

The second solution is that commanders have to embrace their delegated risk level, and then use this freedom to maximise mission command. If a commander assesses a decision is within their own risk level, they can and should execute it without further debate or recourse to a higher commander. When embraced across an organisation, this simple action has the capacity to significantly enhance decentralised execution. This freedom; however, is built on three things: a common understanding of risk, trust throughout the chain, and self-confidence in command. In terms of commonality, we all need to agree on what a ‘MEDIUM’ risk (for example) looks like if we are to work within this space. This takes an investment of time and discussion across the command chain. On trust, everyone in the chain needs to know that they are trusted to act within their delegated risk and will be backed if things go wrong. And finally, commanders must have the self-confidence to work at the edges of their delegated risk: clear in their heads that they have the authority and freedom to do so.

The last solution here is a simple one, but one that is at the heart of success. We must break out of a ‘barracks / training bias’ when considering tactical risk in combat. Central is the recognition of the third aspect of risk beyond ‘likelihood’ and ‘consequence’: that of ‘opportunity’. Tactical success in battle requires us at times to accept, embrace even, the most extreme of risks if we are to gain an edge over a cunning, thinking adversary. The lightning advances of the unarmoured 1st Reconnaissance Battalion during the 2003 invasion of Iraq (as depicted in the series ‘Generation Kill’[2]), for example, were exceptionally high risk but tactically decisive: pulling the remainder of the 1st Marine Division towards Baghdad. At times we have to actively hunt out and pursue such risks if we are to be bold as manoeuvrists: seizing the key terrain, exploiting the uncertain manoeuvre corridor, or acting to deceive and confuse our opponent. But this is hard, especially in the environment of fog, fear and friction that is combat. So, how do we do it?

The best way I have found to exploit this final element is to simply redefine risks as ‘good’ and ‘bad’. By doing so, we explicitly identify risks that we think we should take: bringing ‘opportunity’ to the forefront of briefings, and driving a mindset that analyses, identifies, pursues and embraces good risk for tactical advantage. Good manoeuvrists exploit ‘good risk’ against the enemy, and aggressively terminate ‘bad risks’ that allow the enemy an inherent advantage (often the two are linked). Ideally the ‘good risks’ would be LOW risks with high payoff, but this cannot always be the case. Sometime, as with 1st Recon, the highest risks must be taken. This is hard when the situation is uncertain, but such times are where experience, intuition, analysis and judgement come in: the art of tactical command. In a clear break from the barracks-mindset, phrases such as ‘SFARP’ have less relevance here. It is not about reducing risks so far as reasonably practicable … it is about separating ‘good’ risks from ‘bad’, and then seizing the tactical edge that good risks provide.

Conclusion

Combat is one of the riskiest of human activities. As a ‘duel’ between soldiers and armies it is inherently uncertain, deeply unpredictable, and slave to the principles of chaos. Many tacticians try to deal with this uncertainty by seeking to wrestle it under control: reducing risks as much as they can, and then taking the elephant one low-risk bite at a time. But such a steady, staid approach is too often predictable, conservative and unimaginative. It is easy for a cunning enemy to exploit it, as we saw time and again in Afghanistan and Iraq in the last two decades.

Far better is a tactical approach that seeks to thrive in the chaos of tactical risk. This approach acknowledges the risks inherent in combat, invests effort in identifying ‘good’ from ‘bad’, and then brings the ‘good risks’ into its embrace like an old and trusted friend. Such a focus on ‘good risk’, tied into a trusted environment and with a healthy dose of self-confidence, then acts as a central enabler of mission command. Rapid, decentralised execution follows, as does creativity in tactics.

Despite perceptions to the contrary, Army Risk Management theory gives us all the tools to exploit tactical risk. On top of clear definitions and delegations, it also explicitly recognises ‘opportunity’ in the first paragraph. To really exploit this framework; however, we need to invest time in learning how to use our theory. Mindset is the first step. Commanders must establish a common language and attitude to risk: ‘zeroing the azimuth’ so we all see risk the same. It must become central to tactical discussions. We then need to delineate between the barracks / training and combat environments, understanding when ‘SFARP’ should rightly be at the fore, and when tactical decision-making needs to dominate. We also need to give commanders confidence that if they take a reasonable risk and it bites, we will back them up.

Finally, we need to focus on the difference between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ risks in combat, exploiting the good and terminating the bad to make the best of mission command. The perception that Army is risk-averse is only a reality if we let it be. Get this right, and we will be on the pathway to becoming better tacticians: transforming the risk on our shoulder from a devil, to a guardian angel.

I really enjoyed your argument that commanders should differentiate between 'good’ and ‘bad’ risks in combat. We should exploit the good and terminate the bad to make the best of mission command.

Robert Leonhard in The Art of Maneuver made a similar point that rather than regarding risk as something to be avoided, the practitioner of manoeuvre warfare sees risk as “the coin of the realm” with which they purchases mass. Leonhard defines risk as, 'the inverse of mass'. In other words, in order to create mass in the area of operations that he wishes to influence, he purposely accepts risk in other areas.

In summary, Tom, as you have identified, Army Risk Management theory provides all risk planners with the tools to exploit tactical risk. Thankyou for a well thought out article.