Tourniquet application for combat trauma has demonstrated an overwhelmingly beneficial impact on casualty survival with negligible rates of tourniquet associated morbidity within Middle Eastern conflicts.1-10 These observations have driven the subsequent widespread adoption of liberal pre-hospital tourniquet protocols in both military and civilian trauma care.11-15 The fundamental caveat, however, which has underpinned the favourable results of tourniquet use in Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC), is the assumption of rapid evacuation to higher-level definitive medical care with short ischaemia times.

Within the current Russo-Ukrainian conflict, the application of limb tourniquets with rigid adherence to TCCC protocols has resulted in alarmingly high rates of avoidable limb loss and associated life-threatening secondary morbidity in Ukrainian soldiers.8-10,16-19 Although the exact rates of tourniquet associated complications are difficult to determine due to both operational security and the absence of a functioning trauma registry, multiple sources including the Ukrainian military and United States medical advisors within Ukraine have all agreed that the problem is substantial.9

It has been suggested that the misuse of tourniquets in Ukraine may now be costing more lives and limbs than what they save and that in some hospitals, the majority of limb amputations are conducted to manage the direct complications of tourniquet application rather than injuries sustained because of combat trauma.18,20 Whilst these observations fail to align with our own recent memory of ADF operational experience, it is highly conceivable that future ADF operations are likely to encounter similar problems.

High intensity larger-scale operations, littoral environments, near peer conflict, airspace denial, extended range operations, and grey zone asymmetric warfare all lend themselves to protracted evacuation times, austerity of medical support, and the non-doctrinal reliance on prolonged field care in severely injured casualties.

Avoidable loss of extremities and life is a certainty unless we develop appropriate systems and training for tourniquet de-escalation now. Whilst high tight horizontal fast and ubiquitous tourniquet application is tactically entirely appropriate during Care Under Fire (CUF), these practices also need to be mitigated by robust safety guards in the form of a tourniquet de-escalation framework.

Our current doctrine and training surrounding tourniquet de-escalation is, however, unfit for this purpose.10 Whilst we do currently acknowledge the techniques of tourniquet conversion and tourniquet replacement, they are undervalued and trained in an infrequent ad-hoc manner. Tourniquet conversion is an obscure task in comparison to tourniquet application and the procedure is often unclear, unfocussed, skipped, or forgotten.21 Tourniquet de-escalation recommendations from the Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care (CoTCCC), and by proxy, the ADF, are presently in an underdeveloped state of flux with some of the recommendations being either ambiguous or potentially dangerous.21,22

Tourniquet de-escalation is not a simple binary state of either tourniquet application or tourniquet conversion. De-escalation represents a spectrum of skills and adjuncts used to minimise the impact of tourniquet ischaemia selected according to the clinical presentation, resources available, and an awareness of the tactical environment. Whilst tourniquet removal by approved conversion technique represents the gold standard de-escalation state, this may not be achievable for a variety of clinical or tactical reasons.

Even when tourniquet conversion can’t be achieved, the local and systemic impacts of limb ischaemia can still be mitigated, at least in part. For example, in the presence of large vessel disruption and delayed evacuation requiring extended duration tourniquet application during Prolonged Field Care (PFC), tourniquet revision to the most distally appropriate level together with the application of limb cryotherapy and appropriate systemic trauma resuscitation may represent the best level of care achievable at that point in time. Despite an inability to perform definitive tourniquet conversion, de-escalation of ischaemic risk has still been successfully achieved.

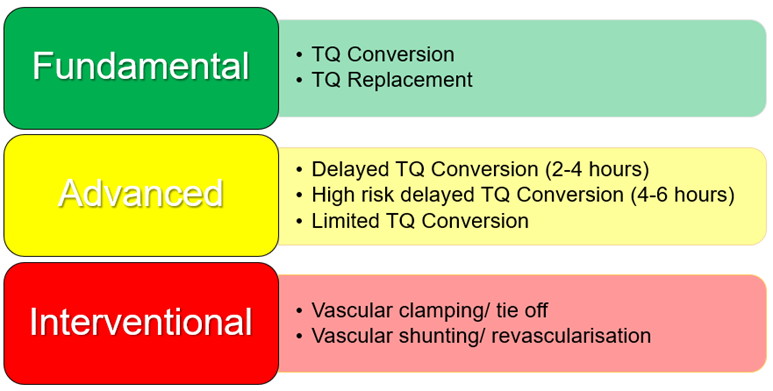

A tourniquet de-escalation skill framework for the ADF could be designed around a three-tiered model (Figure 1). Fundamental level tourniquet de-escalation includes conversion and replacement techniques together with enhanced awareness surrounding the appropriate indications for tourniquet application and a framework for the common understanding of time dependent tissue ischaemia.8,10,23

Advanced level tourniquet de-escalation represents the capability to perform tourniquet conversion in high risk clinical presentations where systemic metabolic impact of reperfusion syndromes are anticipated due to extended durations of limb ischaemia.22 With careful consideration of indications and safety boundaries, limited tourniquet conversion techniques may also be considered to provide intermittent limb reperfusion intervals if tourniquet application beyond two hours is anticipated.24

Interventional level tourniquet de-escalation represents the conduct of emergency procedures to reperfuse a limb after significant vascular injury by either temporary shunting or enabling collateral perfusion by tourniquet conversion after direct vessel ligation.

Figure 1: Tourniquet De-escalation Skill Matrix

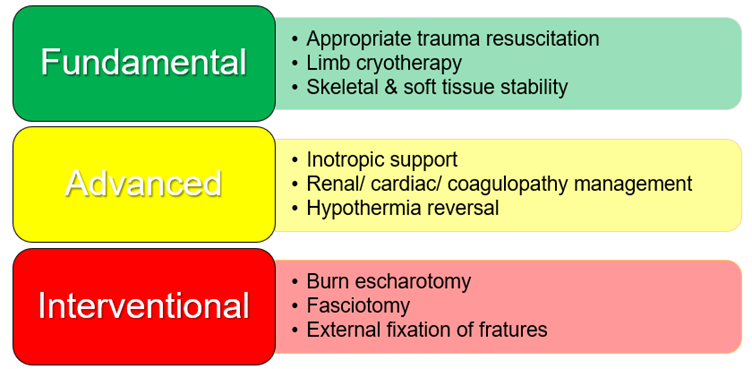

For each level of tourniquet de-escalation there are also associated adjuncts that may be employed to minimise the local impacts of limb trauma and the systemic effects of reperfusion after tourniquet conversion (Figure 2).

Fundamental level tourniquet de-escalation adjuncts include the optimisation of trauma resuscitation by appropriate fluid volume replacement together with administration of tranexamic acid and intravenous antibiotics, where indicated. Reduction in warm ischaemia time by limb cryotherapy may reduce tissue metabolic rate and oxygen consumption with improved limb function and tissue viability for any given duration of tourniquet time.25 Stabilisation of fractures is particularly important after tourniquet conversion as skeletal and soft tissue stability are required to prevent recurrent haemorrhage and haemostatic clot disruption.

Figure 2: Tourniquet De-escalation Adjunct Matrix

Advanced level tourniquet de-escalation adjuncts seek to proactively address the deleterious systemic effects of extended duration tourniquet application and subsequent reperfusion.26 Systemic reperfusion syndromes are influenced by the volume of tissue involved and the duration of warm ischaemia, particularly beyond four hours. Proactive resuscitation prior to tourniquet release is required to address the clinical manifestations of rapid onset hypotension, cardiac arrythmia, metabolic acidosis, hypothermia, and acute renal injury upon limb reperfusion.

Interventional level tourniquet de-escalation adjuncts address surgically correctable factors contributing to limb tissue ischaemia. Escharotomy should be considered for circumferential limb burns with compromised perfusion. Similarly, after extended duration tourniquet application, secondary swelling of ischaemic musculature should be anticipated with limb reperfusion.

Decompressive fasciotomy of fixed volume osteofascial spaces should be undertaken, particularly in the presence of significant vascular injury or where tourniquet times exceed four hours. External fixation of open fractures provides benefit by the combination of skeletal stability, optimised wound access, and soft tissue stabilisation. Skeletal stability is particularly important where temporary vascular shunting or vascular repair has been performed.

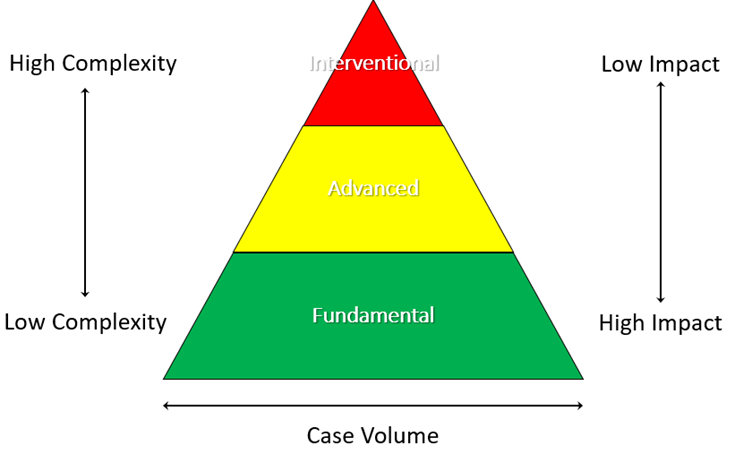

Delivery of a comprehensive tourniquet de-escalation training program within the ADF will need to consider the frequency of skill utilisation, skill complexity, and clinical impact of any interventional skillsets at an organisational level (Figure 3). Fundamental level tourniquet skills and adjuncts represent the highest value proposition in this regard. Tourniquet conversion is the most frequently conducted de-escalation procedure, is simple to perform, and delivers high value clinical and tactical impact.

Interventional de-escalation techniques by comparison apply to substantially fewer casualties, represent a higher degree of skill complexity (typically conducted by a surgeon), and whilst may save a limb from amputation is typically undertaken in the presence of concomitant severe trauma with lower anticipated functional outcomes. Emphasis must therefore be placed upon universal training and continual reaccreditation of fundamental level tourniquet de-escalation skills and adjuncts as they represent high impact, low complexity interventions with the greatest utility.

Figure 3: Tourniquet De-escalation Training – Case volume, Complexity, and Impact.

The question now becomes whom to train and to which level? A sound case could be made that all operational health care providers should be highly proficient at fundamental level tourniquet de-escalation skills and adjuncts. Advanced level tourniquet de-escalation lends itself to delivery at the level of small sized resuscitation teams. Interventional tourniquet de-escalation, traditionally requiring the involvement of surgeons, postulates a more complex discussion.

Do we deploy our limited resource of advanced surgical capabilities forward within a mobility contested environment or can we train selected high-level operational health care teams in the conduct of selected surgical interventions with an extended scope of practice? Could this landscape be further influenced by the evolution and integration of assistive technologies such as telemedicine enabled virtual coaching or advanced offline information systems? 27-35

If we ignore the signs, our lessons will be learned the hard way. The ADF has a window of opportunity to address the identified shortfalls in doctrine and training relating to tourniquet de-escalation. Focus and prioritisation is necessary.

End Notes

1. Butler FK, Jr. TCCC Updates: Two Decades of Saving Lives on the Battlefield: Tactical Combat Casualty Care Turns 20. J Spec Oper Med. 2017;17(2):166-172.

2. Eastridge BJ, Mabry RL, Seguin P, et al. Death on the battlefield (2001-2011): implications for the future of combat casualty care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(6 Suppl 5):S431-437.

3. Kragh JF, Jr., Walters TJ, Baer DG, et al. Survival with emergency tourniquet use to stop bleeding in major limb trauma. Ann Surg. 2009;249(1):1-7.

4. Beekley AC, Sebesta JA, Blackbourne LH, et al. Prehospital tourniquet use in Operation Iraqi Freedom: effect on hemorrhage control and outcomes. J Trauma. 2008;64(2 Suppl):S28-37; discussion S37.

5. Holcomb JB, McMullin NR, Pearse L, et al. Causes of death in U.S. Special Operations Forces in the global war on terrorism: 2001-2004. Ann Surg. 2007;245(6):986-991.

6. Butler FK, Jr., Hagmann J, Butler EG. Tactical combat casualty care in special operations. Mil Med. 1996;161 Suppl:3-16.

7. Kragh JF, Jr., Littrel ML, Jones JA, et al. Battle casualty survival with emergency tourniquet use to stop limb bleeding. J Emerg Med. 2011;41(6):590-597.

8. Holcomb JB, Dorlac WC, Drew BG, et al. Rethinking limb tourniquet conversion in the prehospital environment. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2023;95(6):e54-e60.

9. Butler F, Holcomb JB, Dorlac W, et al. Who needs a tourniquet? And who does not? Lessons learned from a review of tourniquet use in the Russo-Ukrainian war. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2024;97(2S Suppl 1):S45-S54.

10. Patterson JL, Bryan RT, Turconi M, et al. Life Over Limb: Why Not Both? Revisiting Tourniquet Practices Based on Lessons Learned From the War in Ukraine. J Spec Oper Med. 2024.

11. citizenAID. citizenAID - A UK charity empowering the public to save lives. 2024; https://www.citizenaid.org/. Accessed 21 April, 2024.

12. Stop the Bleed Coalition. Stop the Bleed. 2023; https://stopthebleedcoalition.org/project/. Accessed 21 April, 2024.

13. Joint Trauma System. Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care. 2024; https://jts.health.mil/index.cfm/committees/cotccc.

14. Joint Trauma System. Deployed Medicine. 2024; https://deployedmedicine.com/.

15. Committee for Tactical Emergency Casualty Care. c-TECC. 2024; https://www.c-tecc.org/.

16. Quinn J, Panasenko SI, Leshchenko Y, et al. Prehospital Lessons From the War in Ukraine: Damage Control Resuscitation and Surgery Experiences From Point of Injury to Role 2. Mil Med. 2024;189(1-2):17-29.

17. Yatsun V. Application of Hemostatic Tourniquet on Wounded Extremities in Modern "Trench" Warfare: The View of a Vascular Surgeon. Mil Med. 2024;189(1-2):332-336.

18. Stevens RA, Baker MS, Zubach OB, Samotowka M. Misuse of Tourniquets in Ukraine may be Costing More Lives and Limbs than they Save. Mil Med. 2024.

19. Samarskiy IM, Khoroshun EM, Vorokhta Y. The Use of Tourniquets in the Russo-Ukrainian War. J Spec Oper Med. 2024.

20. Hedelin H. Beyond tourniquets: Rethinking haemorrhage control [Internet]; 2024. Podcast

21. Kragh JF. Tourniquet conversion webinar after action review report USAISR 2022. 2022.

22. Weinrauch P. Tourniquet Conversion in an Austere Environment. The Cove. 2023.

23. Weinrauch P. The Tourniquet Traffic Light. The Cove. 2023.

24. Weinrauch P. Limited Tourniquet Conversion in Prolonged Field Care. The Cove. 2023.

25. Weinrauch P. The Limb Exclusion Hypothermia Wrap. The Cove. 2023.

26. Weinrauch P, Peters N. The Reperfusion Toolbox: How to Resuscitate a Casualty in Preparation for Tourniquet Removal after an Extended Duration of Application. The Cove. 2023.

27. Pamplin JC. Telemedicine to reduce medical risk in austere environments. 2018.

28. Prolonged Field Care Collective. Telemedicine Resources. 2024; https://prolongedfieldcare.org/telemed-resources-for-us-mil/. Accessed 21 July, 2024.

29. Mohr CJ, Keenan S. Prolonged Field Care Working Group Position Paper: Operational Context for Prolonged Field Care. J Spec Oper Med. 2015;15(3):78-80.

30. Australian Defence Force. ADF Digital Health Framework 2019 - 2029. 2019.

31. Powell D, McLeroy RD, Riesberg JC, et al. Telemedicine to Reduce Medical Risk in Austere Medical Environments: The Virtual Critical Care Consultation (VC3) Service. J Spec Oper Med. 2016;16(4):102-109.

32. Ball JA, Keenan S. Prolonged Field Care Working Group Position Paper: Prolonged Field Care Capabilities. J Spec Oper Med. 2015;15(3):76-77.

33. Joint Trauma System. Clincial Practice Guideline - Telemedicine Guidance in the Deployed Setting2023.

34. Vasios WN, 3rd, Pamplin JC, Powell D, Loos PE, Riesberg JC, Keenan S. Teleconsultation in Prolonged Field Care Position Paper. J Spec Oper Med. 2017;17(3):141-144.

35. Pamplin JC, Davis KL, Mbuthia J, et al. Military Telehealth: A Model For Delivering Expertise To The Point Of Need In Austere And Operational Environments. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(8):1386-1392.

Thanks for your commentary. Wholly agree that we need to evolve our medical systems and procedures to enhance prolonged field care outside of the doctrinal assumption of uncontested mobility and a 2/30/1 "golden hour".

Tourniquet de-escalation represents a capability that needs to be pushed as far forward as possible. Tourniquet Conversion, Tourniquet Replacement and an awareness of the time dependent impact of tourniquet application should be proficient core skills of very health care provider. More broadly, a good argument could also be made that fundamental level tourniquet de-escalation is an all corps skill that should be delivered during TCCC together with tourniquet application training.

Delivery of more advanced tourniquet de-escalation techniques such as limited tourniquet conversion, conversion in medically higher risk situations and fluid/ blood resuscitation requires appropriate training and resources. Examples might include tourniquet conversion after an extended duration of application or tourniquet conversion in a poly-traumatised hemodynamically unstable casualty. Intermittent release of a tourniquet to achieve reperfusion intervals carries significant risk and should only be conducted by appropriately trained health professionals in defined circumstances with appropriate resources.

Currently the ADF requires improvement in our tourniquet de-escalation doctrine and training at all levels. The aim of this article is to outline a suggested tiered framework of tourniquet de-escalation skills and adjuncts appropriate to provider grade and resource capability.

As a former ARA 031-3 Medic AAMC and Rotary course qualified before it all went very civi based.

Why do we need to reinvent a wheel Ranger Medics have already done?

Excellent points. Tools and protocols for tourniquet de-escalation already exist. In particular, fundamental techniques such as Conversion and Replacement are well described and represent the highest value de-escalation skill set from an organisational perspective (large volume application, low complexity, high impact). I entirely agree that there is no need to reinvent the wheel in this space. Indeed, had these techniques been applied consistently within the current Ukrainian conflict, many lives and limbs would have been saved.

Similarly, the ADF needs to improve our consistency in training and recertification of torniquet de-escalation and a framework to facilitate forward projection of more advanced techniques closer to the point of wounding. This article describes how we might think about tourniquet de-escalation as a graduated spectrum of skills and adjuncts ranging from simple conversion to more advanced surgical interventions. By formalising a tourniquet de-escalation framework we can better define our training requirements and operational capability from both individual and collective viewpoints, which includes the incorporation of established techniques and protocols.

Thanks for the feedback. Appreciated.

I'd love to see these new ideas taught in our training centres.