When reflecting back on 2020 at the Defence Force School of Signals (DFSS), we see a heavily transformative year. Having had no other option than to adapt within Victoria’s COVID situation, it’s a year that has been marked with a lot of forced transformation to enable us to get on with the job. Many of these changes have become sound practice within DFSS and will remain as sustains moving into the future. From this restrictive environment, the DFSS I see leaving 2020 is, in many ways, unrecognisable from the DFSS I marched into in 2019.

What is blended learning? As a preface to the discussion of learning modernisation at DFSS, I would like to explore some often misunderstood terminology. LTCOL Karan’s article[i] provides a good overview of ‘blended learning’ as a concept. However, at DFSS we found such definitions too broad to help our instructors quickly understand the specific implications for their day-to-day requirements. Most military instructors are generalists who spent a few years at a Training Centre before returning to the mainstream Defence Force. Even if they have multiple training postings, few go on to pursue qualifications outside of their service-specific requirements. As such, we identified a need for a more refined model to help focus our instructors’ efforts. This model, styled Facilitate, Self-Paced (FSP) learning, seeks to capture the specific expectations of the interplay between instructors, learners, and Computer-Based Training (CBT) resources. While self-paced learning resources allow learners to progress through lesson content and practical tasks at leisure, instructors facilitate that process by tracking class progress while providing targeted and tailored guidance as required. It is not just putting lesson slides onto ADELE, nor is it just playing videos and letting students work through coursework without an instructor present; it is a combination of engaging self-paced CBT, combined with invested subject matter experts (SME) that together achieves a greater learning outcome than either individually. Giving new signallers radio equipment, little direction and some videos on how to use it is a recipe for disaster. However, replace ‘little direction’ with an instructor contextualising the relevance of the training, time for self-paced learning and adequately-spaced knowledge checks and you have DFSS’ very successful FSP implementation of the Basic Combat Communications Course (BCCC). FSP as a concept helps instructors understand how learners need to engage with their content and how instructors need to engage with both. The result is a marked increase in knowledge retention, student buy-in, and overall enthusiasm in trainees.

Image 1: An ADELE screen giving links to all course modules in order they will be completed in. This is a common view trainees will have when first enrolled into CST that provides links to all of the content they will need. This can be accessed from personal devices at home.

Learning modernisation at DFSS so far. My position at DFSS sits within Network Engineering Wing (NEW) and it is from here I will draw my examples. Prior to 2019, almost all training at NEW was either instructor-driven PowerPoint lectures or instructor-driven practical activities. In 2019, NEW saw the first successful trial of BCCC run using the FSP methodology (known as ‘Student Driven Learning’ at the time). The idea for, and execution of this course came from a small number of instructors who believed strongly that things could be done better. On their own initiative, they spent hours of their time turning 40 minute lectures into multiple, easily-digestible, 3-6 minute short-form videos and structured the course so trainees could access equipment at any time. They produced knowledge checks for each learning milestone along the way and converted the daily training program into a recommended progress guide to determine who was ‘ahead’ or behind’. The Chain of Command absorbed a risk and supported multiple trials of the delivery. The videos were put on laptops for each student and the appropriate equipment and facilitator support was made available. This targeted combination of blended learning techniques worked and received extremely positive feedback from both trainees and staff. I was lucky enough to be a trainee on my RA Sigs Regimental Officer Basic Course during one of these trials in late 2019 and saw the power of this effective blended learning in action. From here I was on board.

Moving into 2020, NEW was keen to maintain the momentum of this success by inducting new staff and applying FSP to other courses. Combine this with a push to modernise through the Future Ready Training System and we saw resourcing to change course content while improve content accessibility through migration onto ADELE(U). By around March, instructors were getting comfortable in their curriculum and were beginning to accelerate the adaptation of Learning Support Material into self-paced CBT. Then COVID-19 struck. While creating CBT for a facilitated course took a lot of effort, social distancing restrictions requiring the limited instructors to spread across multiple classrooms left staff with little alternative. The year’s initial FSP conversion goals became essential to preserving training rather than merely aspirational. Thanks to some incredibly hard work by instructors, support from the Army Education Centre (AEC), and attendance on Military Instructor Courses, this initial panic gave way to certainty as confidence in available tools began to grow. Change was coming. Through trial and error, instructors began to learn how content could be best structured to maximise trainee engagement. Tools such as ‘Articulate 360’ began to present themselves and newer instructors began filming new videos while familiarising themselves with the ‘Camtasia’ editing software. Instructors noted these different learning and instructional styles gave variety and increased learner engagement, where previously a firehose of PowerPoints had often caused a monotonous learning experience. Following the success of the BCCC, a number of routing, telephony, power and other courses were likewise adapted, with each receiving similarly positive feedback.

Virtual Reality content was storyboarded and filmed in-house before being developed by a civilian studio, receiving good reviews from trainees. An Augmented Reality application started development with the same studio and is expected to be implemented at DFSS in 2021. External consultants were brought into DFSS to assess which courses were most likely to benefit from the creation of targeted CBT, then proceeded to create it, producing some excellent content for several critical courses at DFSS. These external pursuits were not without financial cost, but the willingness of the CoC to enable these endeavours has transformed these areas to the benefit of our trainees.

For the first time, a handful of DFSS advanced courses were run completely by distance. Participants were able to access learning material from their home locations while also engaging with staff and peers online. Noting some limitations, most of these courses were very successful, proving the viability of leaving learners with their families rather than spending up to several months on residential courses.

Image 2: Virtual reality training happening in the classroom for the first time. Trainees are answering knowledge retention questions to break up the time spent in the headset. This is immediately prior to a practical where they set up a detachment, it has achieved much better results after viewing the VR content.

Key lessons identified. We found converting traditional Defence instruction to blended learning (specifically, FSP) takes deliberate effort to do properly. There is no one style fits all approach, although FSP comes fairly close. Once the CBT content is created, instructors still need to re-learn their place in the classroom if they wish to facilitate effectively. An instructor, liberated from lecturing, is much better able to circulate the class and address the issues of individual trainees. Those who can accelerate are free to do so, while those requiring assistance receive it without fear of holding up the class. The increased individual engagement increases the quality of the relationships between instructors and trainees, in turn increasing the enjoyment of both. Where attempts at FSP failed, it was typically because the facilitating instructor was using their newfound freedom in ineffective ways. These included interrupting trainees’ efforts to self-pace (too much engagement), and neglecting to provide guidance when required (too little engagement). Facilitating instructors should pay particular attention to this dynamic and ensure their level of engagement is calibrated appropriately.

Appropriate course ‘scaffolding’ is essential to enabling the ‘self-paced’ aspect of FSP learning. This means ensuring the learning outcomes (often the assessment requirement) are well understood by the learning audience and that all course material is appropriately aligned. Where an LMP’s teaching points do not contribute to the learning outcomes, they should be reviewed for removal, or the assessment adjusted. Learning resources likewise should be well organised, with suitable learning checks interspaced to validate trainee progress while acting as a tool for facilitator tracking. If this isn’t done, trainees often become lost, or even despondent instead of focused and engaged. Similarly, without a sense of where learners should be on any particular day, facilitating instructors are unable to gauge who needs more help until it is too late.

There are notable exceptions to ‘self-paced’ delivery, particularly where safety and security considerations are a factor. Where risk to personnel or equipment is high, or requires increased instructor ratios, the course must be correspondingly adjusted to compensate.

End of year handovers are a reality of military life. This handover period needs to be well-managed by the CoC to ensure staff posting into the unit gain appropriate training either prior to or early into their tenure. Engagement with AEC has proven extremely effective for educating instructors on the full range of available content development tools while affording opportunities for practice. Within NEW we also captured our lessons from throughout the year for incorporation into DFSS’ 2021 induction.

While COVID-19 provided significant impetus, CoC assistance was essential. The enabling effects from higher headquarters, whether it be funding or simply top cover for trying something new, have been agile, and therefore instrumental in giving instructors the freedom of action to go forth and innovate. This freedom to ‘choose your own adventure’ has seen staff from all backgrounds and levels of initial enthusiasm produce and implement training materials of great value.

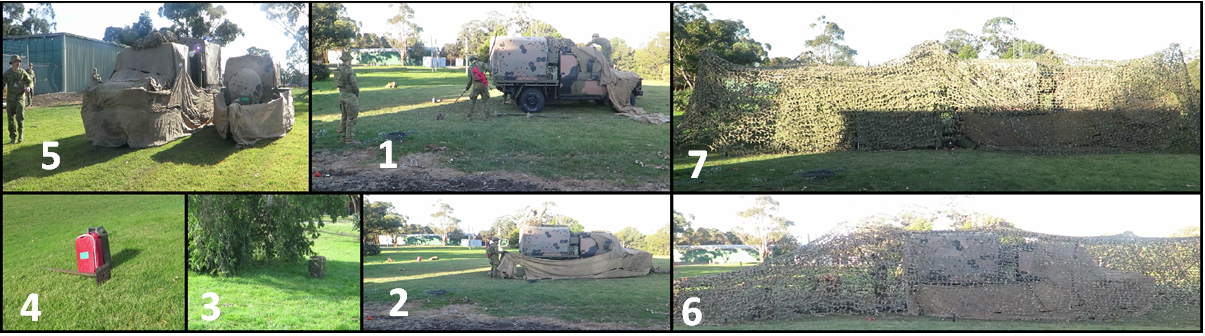

Image 3: Screenshots from a typical training video. This particular example is from how to deploy an RA Sigs detachment, it runs for around 4 minutes and details, with voiceover, all the doctrinal steps involved, from deploying vehicle scrim to setting up fire points, POL points through to cam-net completion.

Final Word. This process required a substantial time investment to achieve classroom-readiness. However, once established this process reaps a more engaging, effective and scalable learning product which is ultimately where FSP’s merit lies. We have seen a marked benefit to trainees, often demonstrated through increased buy in on their end, greater knowledge and greater enthusiasm overall. Instructors have reported lower levels of fatigue from the monotony of lecturing as well as better quality relationships with the trainees under their guidance. As we move to the end of 2020, this reflection has been beneficial for NEW as we begin to hand over to the 2021 crew. I would encourage any Training Establishment going through a similar modernisation process to do the same to ensure they continue to move forward into the future and don’t lose valuable lessons that could otherwise be passed along. FSP has now become the norm in DFSS, it is hard to overstate how effective and beneficial this has been regardless of the required initial investment. Any individual or organisation considering making the change moving forward should jump at the opportunity, it is most definitely worth the effort.

[i] Article by CO Army Education Centre LTCOL Nileshni Karan exploring the concept of Blended Learning.

We need to be mindful that ‘time spent on course’, or ‘time spent learning’, may not actually be diminished, but ‘time spent concentrated/co-located’ may be reduced by employing relevant learning aids. Incorporating XR tools, those learning aids involve XR, impose a reconsideration of how ‘training’ is delivered. Individual XR brings multi-million dollar ‘simulators’ to the individual level. XR allows learners to learn at their own pace, revise, rehearse and reiterate their learning, when best suits them, rather than in a lock-step classroom. However, we must consider all aspects of learning for Army people; we work in a team environment; learning alone, without team reinforcement, will likely hinder the development of unity, and therefore hinder Army completing its mission. Time spent concentrated/co-located is still relevant, even if the basics are learned individually, at the learners own pace. Instructors still need to be involved to ensure correct behaviours, attitudes, skills and knowledge are inculcated in the individual learning phases.

Team XR environments enable group interaction (subject to real-time platforms). However, we still need to develop authentic relationships and genuine resilience under pressure. Trust is developed face-to-face. Time spent concentrated/co-located is not just relevant, it is essential.

At DFSS, we’ve seen instructors get self-paced learning wrong by assuming they can leave learners to figure it all out on their own. Things fall apart quickly when learners don’t feel supported and the relevance of the subject isn’t properly reinforced.

for instructors of today and tomorrow see where have come from and how paradigm changes were triggered.