‘The Australian Army is to prepare land forces for war in order to defend Australia and its National Interests.’

– Australian Army Mission

Over the last two years the Australian Army has come to an important conclusion. The world is on the cusp of a significant change in the character of warfare. Evidence of this is rife. Cyber warfare is now a reality, and cyber-attacks (both criminal and state-based) are proliferating. Artificial Intelligence (AI), robotics and quantum computing are rapidly influencing every element of life, and it is clear that warfare will be no different. The range of potential threats we face is growing: from natural disasters, through the persistence of fanatical terrorism, and to the spectre of nuclear confrontation in the Korean Peninsula. The battlespace is both blurring and expanding rapidly.

So what? All of this presents challenges to Australia, and to the Australian Army. We are and will remain a comparatively small force. As the character of warfare evolves it is clear we must also evolve. This is why last week the Chief of Army approved a Professional Military Education (PME) Strategy to achieve a competitive advantage over our adversaries: an intellectual edge that will help us orientate, contextualise, plan, decide and successfully act faster than the enemy.

This article will introduce you to the Strategy. It will cover its evolution, the assumptions that were made to develop it, and the outcomes. The aim at the end is that you will go and read the Strategy itself – a quick win at just ten pages – to see how we will grow the intellectual edge that will help us win in the future.

The Problem – Future Warfare

The development of Army’s PME Strategy started with the identification of a problem: that warfare is on a path to become even more complex, and that Army (like everyone else) is going to find this environment challenging. The best way to understand this is to review Defence’s published work on the future of war. The Defence White Paper 2016, the VCDF Group’s Future Operating Environment 2035, the Army’s Future Land Warfare Report 2014, and studies from our allied partners all paint a pretty bleak picture of the future. Three trends, or problems, stand out for the Australian Army. In brief they are:

- Australia’s Demography. As a nation we only have 8.5 million military-fit citizens. Projected population growth shows this isn’t going to change. We will always have a relatively small force in the region.

- The Spread of Technological Parity. We have long relied on a technological edge to offset our lack of mass. However this is declining as sophisticated technology becomes more accessible to state and non-state actors. We are losing our technological edge.

- The Potential Impact of Emerging Technologies. The fourth technical revolution is upon us, and AI, ‘deep learning’ systems and man / machine teaming are only years away. These technologies, which will be widely available, will fundamentally challenge our traditional way of war.

These three simple trends are very important. They mean that in the future it is highly likely we will be a relatively small force, with a declining technological edge, fighting in a hyper-technical and lethal battlespace. A challenging place to be.

For those of us working on training and education in TRADOC this confirmed that Army needs something new. Our equipment is already on a clear road to modernisation, but we need to match this with an investment into our people. We need a new edge. We came to believe that the answer lay in our intellect. Our future success relies on our ability to define problems, develop solutions, and make the right decision at the best time: to adapt in the face of adversity. If we could come up with a way to improve our thinking, and consistently make better choices than our enemies, we would gain a competitive advantage. The idea of the intellectual edge was born.

Armed with this idea, and the responsibility to help prepare Army for war, we set out to develop a solution. We started (as is often the case with planning in an uncertain environment) by building assumptions and asking for commander’s guidance.

Planning in an Uncertain World: Assumptions and Commander’s Guidance

The four assumptions were:

- Assumption 1: The character of war is changing, but the nature of war endures. This idea sounds complex but is actually quite simple. We wanted to be able to assume that, while factors like AI and robotics will change the character of war, war will fundamentally remain a human activity. Friction, geography, uncertainty, politics, human emotions – all the things which have characterised war for thousands of years – will remain central. This means that one can continue to rely on long-standing ideas like capstone doctrine and the principles of war. It balances the need for change.

- Assumption 2: Predictions on the rate of technical change are conservative. We wanted to assume that our current assessments of the pace of incoming technology were probably conservative. AI (for example) would become a part of warfare in years, not decades. This gives urgency for change.

- Assumption 3: Army’s mission will endure for five years. The mission for the Australian Army was revised in 2017, and provides great clarity. ‘Prepare’, for example, indicates the need to make the Army ready for combat - but likely operating under command of a joint force. ‘War’ makes the battlefield clear. ‘Defend’, ‘Australia’ and ‘National Interest’ all help to define how we will fight. We wanted to assume that this wouldn’t change for five years. This manages the scale of change.

- Assumption 4: Multiple domains will challenge traditional structures. In the last two years we have seen the growth of the multi-domain battle concept. The US Army particularly has concluded that fighting across (and thriving within) multiple domains will be key to future warfare. Australia is on a similar path. We wanted to assume that this multi-domain move would increasingly challenge our traditional structures of single-services and hierarchical units. This gives us scope for change.

The four freedoms were:

- Freedom 1: The rebalancing of time and resources. A new edge wasn’t going to come at zero cost. Professional development is a cheap date in comparison with major programs, but it still needs resourcing. Time is always going to be the most valuable commodity. So we asked the Chief for the freedom to genuinely drive a re-prioritisation of funding, resources and (most importantly) time to the development of a new intellectual edge.

- Freedom 2: Adjustments of the levers of cultural change. The Ryan Review concluded that the current Australian Army culture places limited value in intellect. Intellect, for example, is not one of the seven facets of Army culture listed in Land Warfare Doctrine 1, Army’s capstone doctrine. If we wanted an intellectual edge, we were going to need to slowly adjust this. We would need to persuade Army to value intellectual development – to promote it as a core part of our culture. To do this we asked for the freedom to apply levers: doctrine, career, values, and others.

- Freedom 3: One Strategy for Army. Different commands in Army were always going to have slightly different needs. Forces Command would need a solution that could work at scale, across multiple brigades. Special Operations would need the breadth to be unconventional. But we also knew that, to be successful, the intellectual edge would have to be embraced by Army writ large. So we asked the Chief for the freedom to design one solution, to be adopted by the whole force.

- Freedom 4: Alignment with Joint and Other Service PME. Finally we asked for the freedom to align the intellectual edge with the conceptual developments of our sister services. Plans Jericho and Pelorus each have their own pathways towards an intellectual edge. In the spirit of breaking down domains, we wanted to be able to lean into these… even if it came at short term cost to Army.

These assumptions and freedoms were critical. They provided us with an idea of just how far we could reach, and how bold we could be. Vitally they gave us a window into our highest commander’s intent. Once we had them in place we were able to move towards designing a solution.

The Solution – Evolving an Intellectual Edge

Army’s PME Strategy is only ten pages long, but this conceals over nine months of development. The initial idea of an intellectual edge was refined through the broadest possible consultation, using the assumptions and freedoms given by the Chief. Serving soldiers and officers from Private to Lieutenant General were asked for their input and guidance. Australia’s top academics were tapped for ideas. Allies were consulted. Discussion papers were published. The result is a broad and flexible Strategy that will guide Army over time to an intellectual edge.

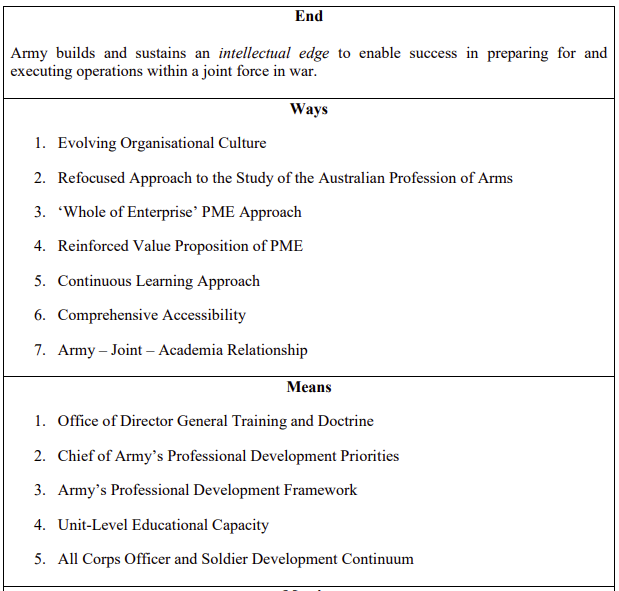

You can see the Strategy in simple form in the table below.

The easiest way to look at it is to break down the constituent parts. The ‘ways’ are the design criteria for our future investment in intellectual development. All of our efforts should adhere to these as far as possible – evolving culture, focussed on the profession, comprehensively accessible, and so on. The ‘means’ are then the flexible tools and concepts we will use to get there. Finally the ‘end’ is exactly that … our vision of the future and where we want to end up. If these pique your interest and you want to know more, you just need to read the Strategy. It’s only ten pages.

The Next Steps – Building Momentum

The development of Army’s PME Strategy was a keynote effort for TRADOC this year. 2018 is all about delivery. We want to show that the intellectual edge has value. We believe initiatives like The Cove and the reenergising of doctrine have sparked a small fire of cultural change in the force. We now want to fan these flames by delivering results where it matters most; in the Battalions and Regiments of the Australian Army.